As the MLK holiday approaches, I submit for your consideration the name of baseball maverick Bill Veeck. Those of you who are not big baseball fans (or too young) might not know of this colorful and visionary team owner who shook up the establishment with his stunts, fan promotions, exploding scoreboards and so much more. For good or bad, he is probably most remembered for sending 3-foot-7-inch Eddie Gaedel to the plate in a major league game (Eddie wore uniform number 1/8 and walked on 4 pitches). But here is another fact: Veeck marched (on his one good leg and a wooden one) in Martin Luther King’s funeral procession in Atlanta in 1968. This is a story of why that march was in character for this man and why he has a key role in the history arc covered by Kansas City’s Negro Leagues Baseball Museum.

Many years ago, I read Veeck’s 1962 autobiography Veeck–as in Wreck. I remember loving the book, but my retention was more about his baseball operations than his humanity. I recently got a refresher course on Veeck’s good works from a new biography: Bill Veeck/Baseball’s Greatest Maverick by Paul Dickson. As almost everyone knows, Jackie Robinson broke the baseball color line in the National League in 1947 with Branch Rickey’s Brooklyn Dodgers. In what is almost just a footnote, the American League was integrated 12 weeks later when Larry Doby entered the lineup for Bill Veeck’s Cleveland Indians.

Veeck had been promoting baseball integration for many years. He was a fan of the Negro Leagues in the 1920’s and 30’s and admired talented stars such as Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson. In Veeck–as in Wreck, Veeck says he tried to purchase the struggling Philadelphia Phillies in 1942 and stock it with Negro League players, only to be rebuffed by the commissioner and owners. With African-Americans serving in WW II, Veeck thought it was an opportune time to make this move. The establishment position was echoed by a 1942 editorial in The Sporting News (the so-called “Bible of Baseball”) listing reasons why integration would not work and criticized “agitators” acting like “great crusaders in the guise of democracy.” In 1943, Ricky became general manager of the Dodgers. In 1946, Veeck bought the Cleveland Indians. In 1947, these two crusaders proved The Sporting News and the establishment wrong.

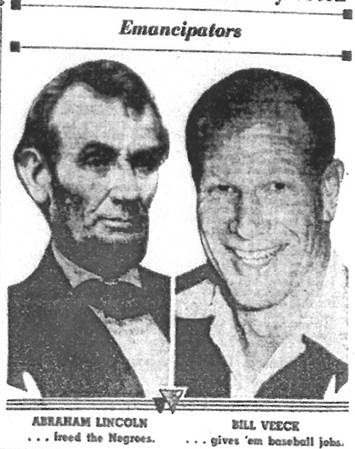

Veeck did not just recruit African-American players, he fought hotels and restaurants unwilling to serve them. He integrated all levels of his operations from vendors to the front office. He tweaked his fellow American League owners for their failure to aggressively sign African-American players. He worried that the National League would get more stars and as usual he was right – the A’s turned down Hank Aaron and the Yankees passed on Willie Mays. Veeck’s efforts were nicely summarized in a 1949 article in, of all places, The Sporting News, pairing him with Abraham Lincoln as “Emancipators”: “Lincoln…freed the Negroes” and Veeck…gives ‘em baseball jobs.”

To round out my Veeck refresher course, I revisited the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum at 18th and Vine in Kansas City. The museum is much more than a memorabilia collection. As one winds through the baseball exhibits, there is a parallel timeline along the lower edge that places the Negro Leagues history in context with civil rights milestones. The timeline starts with the Emancipation Proclamation when baseball was in its infancy and then moves to the effective legalization of segregated baseball via Jim Crow laws and the 1896 Supreme Court “separate but equal” decision. African-American players were left to barnstorming and playing in weak leagues often run by white owners. Starting in about 1910, the first Great Migration added many potential new African-American fans to Midwest cities. Sensing an opportunity, a group of African-American club owners met in Kansas City at the Paseo YMCA and formed the Negro National League (there was one white owner, J.L. Wilkinson of the Kansas City Monarchs).

As the Negro Leagues went through good times and bad, the timeline continues: the Depression; the segregated armed forces of World War II; on April 10, 1947, the Congress of Racial Equality began bus rides through the south, a precursor to the Freedom Rider movement of the 60’s; five days later on April 15, Jackie Robinson began play for the Dodgers; in 1948, President Truman desegregated the armed services; and finally the Civil Rights Movement during which the Major Leagues became fully integrated and the Negro Leagues faded away – a victim of their own success.

The importance of the Kansas City Monarchs to integration of the majors is best shown in an exhibit featuring the first African-American player for each of the then 16 major league teams. Monarchs players were the first to play for the Dodgers, Browns, Giants, Cubs, Pirates, Yankees and Phillies (7 of 16). These included Jackie Robinson, Ernie Banks (“Mr. Cub”) and the Yankees’ Elston Howard. Banks and Howard had played together in Kansas City for revered Monarchs’ manager Buck O’Neil. But integration of baseball was far from an accelerated process. When Robinson broke the color line in 1947, I was in kindergarten. It would be the summer after I graduated from high school in 1959 that owner Tom Yawkey finally relented and allowed an African-American player on his Red Sox roster, at long last integrating all 16 teams.

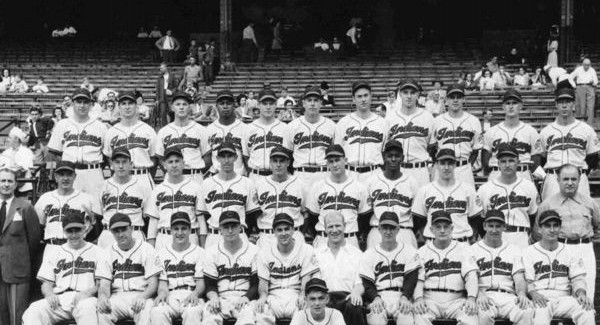

One of my favorite items at the museum is a 1948 World Series program opened to the team picture of Bill Veeck’s Cleveland Indians. A smiling Veeck is in the center of the photo and the surrounding players include Larry Doby and the popular Satchel Paige standing in the middle row next to another pitching great, Bob Feller.

Paige had moved from the Monarchs to the Indians in 1948 as a 42-year old “rookie.” The Sporting News attacked Veeck for signing the “old man,” saying “If Paige were white, he would not have drawn a second thought from Veeck.” Veeck’s comeback: “If Satch were white, of course, he would have been in the majors 25 years earlier.” Satch had a good season for the Indians and brought record crowds – in his first three starts, he drew 201,829 fans. Satch became the first African-American to pitch in the World Series and Doby was the first to hit a homer. The Indians won the Series. Below, Paige (seated) and Doby.

One last anecdote about Veeck. He was a Marine in WW II and suffered a bad foot injury that led to a series of amputations and ultimately a prosthetic wooden leg. He never felt sorry for himself and in a characteristic Veeck move, he carved an ashtray in the hollow leg to service his chain-smoking. He used his condition to teach a profound lesson in Veeck–as in Wreck:

“What offends me about prejudice, I think, is that it assumes a totally unwarranted superiority. For as long as I can remember I have felt vaguely uneasy when anybody tells me an anti-Negro or anti-Semitic or anti-Catholic joke. It only takes one leg, you know, to walk away.”

As we honor the legacy of Martin Luther King with the coming holiday, please also remember Jackie Robinson and Larry Doby, men who braved hostile and bigoted crowds (and fellow players) and played a seminal role in the emerging Civil Rights Movement. And also Bill Veeck, a maverick for all the right reasons. Definitely in a league of his own. Finally, I encourage you to accept Buck O’Neil’s gracious perpetual invitation to visit the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum to see more of the story.