[When my law firm added Martin Luther King Jr. Day as a holiday in 2002, I began an annual message within the firm about why we celebrate the holiday. The distribution was later expanded outside the firm, and since 2016 the message has been circulated as a Hot Stove post. Below, my 18th annual MLK message.]

One of the best ways to appreciate Martin Luther King Jr. Day is to visit the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City. Not just for the memorabilia collection – although that is well worth the trip. There is also a compelling civil rights lesson. As one walks through the baseball exhibits, there is a parallel timeline along the lower edge that places Negro Leagues history in context with civil rights milestones.

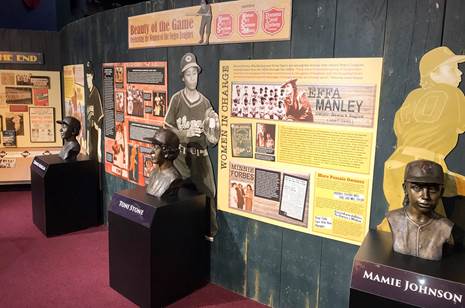

In a new exhibit added last year – “Beauty of the Game” – the museum honors the contribution of women both on and off the field. The exhibit features three women who played in the Negro Leagues (Mamie “Peanuts” Johnson, Toni Stone and Connie Morgan), plus one executive, Effa Manley.

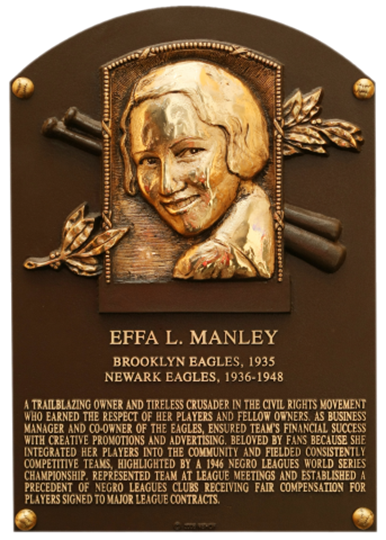

Effa Manley is also featured in another well-known museum. She is the only woman ever inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame. There are 324 men. Below is her plaque at Cooperstown:

Abe and Effa: Effa Louise Brooks grew up in Philadelphia and moved to Harlem after graduating from high school in 1916. She met Abe Manley in the early 1930’s and they married in 1933. They were both baseball fans. Effa went to games at Yankee Stadium (“I was crazy about Babe Ruth”). Abe went to Negro League games when he lived in Pennsylvania and became friends with many of the players. He also once owned a semipro team. Legend has it that Abe and Effa met at Yankee Stadium during the 1932 World Series.

Effa and Abe each brought an interesting backstory. Effa’s maternal grandparents were German and Native American. Her father might have been her mother’s black husband or white boss. Whatever the correct story, Effa lived her life as a black woman married to a black man (actually four, the marriage to Abe plus three short-termers). Abe was in the numbers racket and some of his excess funds would come in handy to own a baseball team. At least two other Negro League teams were similarly capitalized – it’s not like there was a lot spare capital in the black community.

Negro National League (NNL): The original Negro National League was formed in 1920 at the Paseo YMCA in Kansas City. The KC Monarchs joined the league and became one of its premier teams. The league was forced to disband during the Depression, but it was revived in 1933. However, the Monarchs did not rejoin, but instead became a member of the new Negro American League (NAL) formed in 1937.

In 1935, Abe Manley formed the Brooklyn Eagles as a franchise in the NNL. He moved the team to Newark the following year, and the team played as the Newark Eagles from 1936 to 1948. Effa became Abe’s partner in the business and soon took over the day-to-day operations. Abe liked the social side – traveling with the players and swapping stories – the team was his “hobby” according to Effa. She did almost everything else: setting playing schedules, booking travel, managing payroll, buying equipment, negotiating contracts, dealing with the press and handling publicity. She was a trailblazer on creative promotions to draw fans. She was also very active in the community and counselled her players to do the same. She became the public face of the Eagles.

Effa was also an active participant in league matters. There, not to the pleasure of some owners, she was outspoken and demanding. Gus Greenlee, owner of the Pittsburgh Crawfords (and, like Abe, a numbers runner), was president of the league in the early years. His initial take on Effa: “The proper place for women is by the fireside, not functioning in positions to which their husbands have been elected.” Sportswriter Dan Burly wrote that Effa was a “sore spot” with other owners “who have complained often and loudly that ‘baseball ain’t no place for no woman. We can’t even cuss her out.’”

Greenlee learned to deal with Effa, and this leads to a Satchel Paige story. In Larry Tye’s biography of Satchel, the author writes that “[Effa] also was renowned across blackball for her willingness to battle on behalf of both the Newark Eagles and civil rights, her pioneering role as the sole woman of consequence in the fraternity of the Negro Leagues, and her flirtations and more with her husband’s ballplayers.” It is that last item that lends some context to the Satchel story.

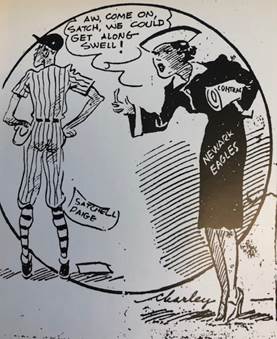

Paige had played for Greenlee’s Pittsburgh Crawfords in 1936 and then jumped to a Dominican Republic team for 1937. He was potentially returning to the states in 1938, but Greenlee was tired of chasing him and sold his contract to the Eagles. As Effa told the story in a 1977 interview, “Satchel wrote me and told me he’d come to the team if I’d be his girlfriend…I was kind of cute then too…I didn’t even answer his letter.” Satchel’s letter was a little ambiguous: “I am yours for the asking if it can be possible for me to get there…I am a man tell me just what you want to know, and please answer the things I ask you.” Satchel instead pitched in Mexico in 1938 and never joined the Eagles. But Effa’s role was memorialized in the press:

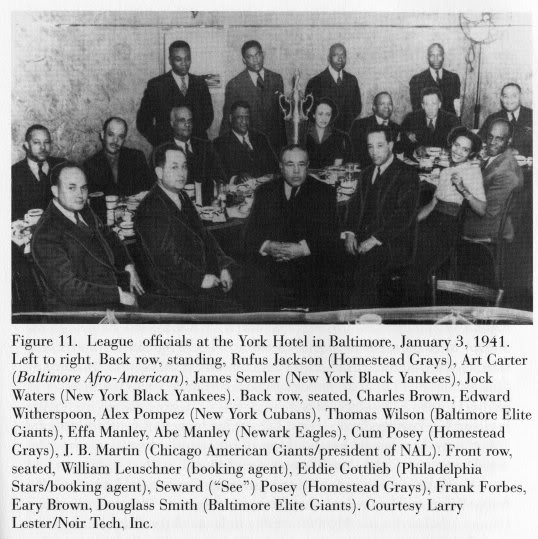

Effa became a force in the league. She pushed for a more businesslike operation and rules to deter players from jumping teams. She argued for an outside commissioner. Her hard work and perseverance brought a grudging respect. In the end, as shown in the photo below, she was “in the room where it happens.”

Effa as Civil Rights and Community Activist: Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King, Jr. came to national attention in 1955 in the bus boycott in Montgomery. That was 21 years after Effa Manley led a civil rights boycott.

Effa was an influential member of the local chapter of the NAACP and the Citizens League for Fair Play. In 1934, she spearheaded the “Don’t Buy Where You Can’t Work” campaign that called for a boycott of Harlem retail stores that would not hire black clerks. One of the key moments was a pivotal meeting between Citizens League leaders, including Effa, and the owner of Blumstein’s, a major department store. The result was a big success.

In April of 1939, Billie Holiday (below) released “Strange Fruit” – the protest song that reenergized the fight for anti-lynching laws. Effa took up the cause that summer with the first of her “Anti-Lynching” days at the ballpark. The ushers wore “Stop Lynching” sashes and collected money from the crowd for anti-lynching causes. [Anti-Lynching Law Update: Since 1901, some 240 attempts have been made in Congress to pass an anti-lynching law. All have failed. In 2005, the Senate issued an apology for its past legislative failures. Lynching is no longer the common form of racist killing, but symbolically, it has remained a blemish. Last month, the Senate unanimously passed an anti-lynching bill – ironically, the presiding officer during the Senate vote was Cindy Hyde-Smith who recently used the term “public hanging” as an “exaggerated expression of regard” for a campaign supporter. The bill was not brought up in the House before the session ended, so the process will need to start again in 2019.]

Other civil rights and charitable causes were regularly given fund raising nights at Eagles games. During the war, funds were raised for bonds and relief efforts. Effa recruited or shamed other teams into participating to raise funds for the NAACP, the Red Cross and community hospitals, among others. As a local paper wrote, “She was one of the few blacks who had a little money, and she put some back into the community.”

And by her actions if not her words, Effa fought for the equality of women in management long before it was fashionable.

The Eagles Players: Abe and Effa’s Eagles had three future Hall of Famers in the infield in the late 1930’s. They were referred to as the “Million Dollar Infield” although this was hyperbole – most players (black or white, stars or not) were not making big money in those days. The first baseman was Mule Suttles, one of the great power hitters in the Negro Leagues. [That’s Mule with Effa below. Effa always dressed fashionably, usually with a fine hat, even at the games. But a photographer talked her into wearing a team cap for this photo op.]

The third baseman was Ray Dandridge. It was said that a train could go through his bowlegs, but that a baseball never did. Shortstop Willie Wells was so good that he was touted as a replacement for the Dodgers’ Pee Wee Reese who had been drafted for the war in 1942. It was the right major league team, but the wrong year – the Dodgers would break the color line with Jackie Robinson five years later.

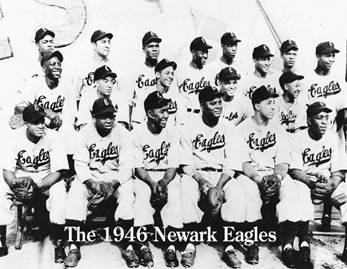

Newark continued to add good players who helped the Eagles to mostly winning seasons in the 1940’s. The Million Dollar Infield was joined by four more future Hall of Famers: Leon Day, Biz Mackey, Monte Irvin and Larry Doby. The team won the NNL pennant in 1946 and then beat the NAL Kansas City Monarchs in the Negro League World Series.

The World Series glory was short lived. The good young ballplayers were being recruited by the majors and the Negro Leagues began to decline.

Effa Manley v. Branch Rickey: Even before the successful 1946 season, Effa felt the sting of losing a star to “organized” baseball. After Brooklyn’s Branch Rickey signed the Monarchs’ Jackie Robinson in 1945, his next two big signings were in April of 1946: Roy Campanella of the Baltimore Elite Giants and Don Newcombe of Effa’s Newark Eagles. Robinson made it to the majors in 1947, and the other two soon followed.

Effa of course did not like losing good players, but she realized that integration of baseball was a victory for the community. But what rankled her was that Rickey was poaching players without any recognition that Negro League teams had developed the players. She thought compensation was justified, but Rickey refused. Despite some bad press for interfering with the integration of baseball, Effa would not be silenced. And her perseverance paid off. Her stars Larry Doby and Monte Irvin both had feelers from Branch Rickey, but ended up with teams who were willing to compensate the Eagles.

Branch Rickey was set to sign Doby, but backed off when Cleveland owner Bill Veeck entered the picture. Rickey knew it would be good to have a second team integrate, especially one in the American League. So Doby signed with the Indians in July of 1947. Veeck knew that Effa had no leverage to get compensation for Doby. But Veeck was no Branch Rickey. The Indians paid $15,000 to the Eagles. More importantly, Effa had established a precedent that ultimately benefitted all of the Negro League teams (as so noted on her Cooperstown plaque).

The Manleys sold the Eagles after the 1948 season, but Effa still had a connection to her star Monte Irvin: the terms of the sale provided that the Manleys and the new owners would share any money received if a major league team paid for one of the players. This was potentially a moot point when Branch Rickey signed Irvin with no intent to pay the Eagles. Effa fought back claiming that the Irvin had a contract and that she would contest the signing. Rickey backed off and Effa made a deal with Horace Stoneham of the Giants for $5,000. After paying lawyer fees and giving a share to the new owners, Effa got $1,250. She used the money to buy a mink stole.

Some Major League Highlights of Former Eagles: Larry Doby broke the color line in the American League in July of 1947. The next year, he became the first black player to hit a home run in a World Series, helping the Indians win their second title (they have not won since). Newcombe was the NL Rookie of the Year in 1949 and was both the MVP and Cy Young winner in 1956.

In 1951, Monte Irvin led the NL in RBI’s and was instrumental in the famed comeback by the Giants to catch the Dodgers to force a three-game playoff for the pennant. Irvin got a hit in each playoff game, including a homer to help win the first game. In Game 3, Newcombe started the game, but was relieved in the ninth by Ralph Branca who gave up the famous 3-run homer to Bobby Thomson. The Giants then met the Yankees in the World Series where Irvin became part of history by playing in the first all-black Series outfield alongside two fellow former Negro Leaguers (Willie Mays of the Birmingham Black Barons and Hank Johnson of the Kansas City Monarchs). Irvin ignited a Game 1 victory for the Giants by stealing home in the first inning on Yogi Berra. Irvin went on to hit .458 in the Series, but the Yankees won in six games. Irvin was on a Series winner in 1954 when the Giants beat the Indians.

After the Eagles: After the Eagles were sold, Effa continued her work in community and civil rights organizations. But her true cause was keeping alive the history of the Negro Leagues and pushing for the induction of Negro League players into the National Baseball Hall of Fame. She finally saw some movement in the early 1970’s as Satchel Paige was inducted in 1971, followed by five other players through 1975.

To emphasize that many more should be inducted, Effa self-published a book with sportswriter Leon Hardwick in 1976 titled Negro Baseball – Before Integration. Included are 73 biographies of players she felt should be considered for enshrinement. Progress remained slow with only three more players being added before the special committee to add Negro Leaguers was disbanded in 1977. The 80-year-old Effa Manley still had her voice, “Why in the hell did the Hall of Fame set that committee up, if they were going to do the lousy job they did?”

She fired off letters to the Hall of Fame, Commissioner Bowie Kuhn and C. C. Johnson Spink, publisher of The Sporting News: “I would settle for 30 players, but I could name 100.” Spink’s column of June 20, 1977, seemed receptive to this crusade by a “furious woman.” She liked that description and saved the clipping.

In 1978, Effa was the special honoree at the Second Annual Negro Baseball League Reunion. Monte Irvin was there and saw Effa wearing her mink stole. He asked if it was the one she got from her sale of Irvin’s contract to the Giants. “Yes, it still looks good and keeps me warm.”

It would take another quarter century, but some 35 Negro Leaguers now have plaques alongside Babe Ruth, Ty Cobb and other greats in Cooperstown. Effa’s Newark Eagles are well represented. The team played from 1936 to 1948, just 13 years. But that was enough time for seven Hall of Famers to play a good part of their career in Newark. [To put this in perspective, the Royals have played 50 seasons and produced one Hall of Fame player, George Brett.]

The Eagles of course have another representative in the Hall of Fame – the team’s top executive, Effa Manley. She was inducted in 2006.

Effa’s Hall of Fame induction was a posthumous award. She died in 1981 at age 84. Inscribed on her gravestone: “She Loved Baseball.”

Lonnie’s Jukebox: Three selections today. For those of a certain age (teenagers in the 50’s/60’s), you may remember that you paid a quarter for three plays on the jukebox. These are free.

First, the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum. I urge everyone to attend and buy a membership. When you walk through the Field of Legends, you will see two of Effa’s players, Ray Dandridge at third base and Leon Day in right field. The player she could not sign, the elusive Satchel Paige, is on the mound. This clip shows NLBM President Bob Kendrick describing the “Beauty of the Game” exhibit (2:30).

Second, the 1992 movie A League of Their Own. This is on my mind because director Penny Marshall died last month, and scenes from the movie have been popping up on social media. I have always been a fan of the movie. From Geena Davis to Tom Hanks to Madonna, the acting is superb, although I single out as my personal favorite Jon Lovitz as the hilarious baseball scout.

Joe Posnanski did a column on his 10 favorite things about the movie, and one of his points reminded me of the subtle civil rights message. The real-life “league of their own” was segregated just like its male counterpart. In a mere 15 seconds, the movie tells a very big story of the times. A black woman has left her seat – from what is obviously the segregated seating area down the right field line – to retrieve and throw back an errant ball. She does so with obvious talent, and the message is that she is not racially eligible to play in the game. See the clip here.

In 2014, Penny Marshall announced that she planned to direct another baseball movie, this one about the life of Effa Manley. The screenplay is by writer Byron Motley, the son of Bob Motley, the Negro League umpire who this past year was honored with his own statue on the Field of Legends (behind the catcher at home plate in the NLBM photo above). I checked in with Byron, and he tells me that the project is still moving forward and to “stay tuned.” Byron’s tribute to Penny is here.

And third, the classic protest song “What’s Going On” by Marvin Gaye. As the turbulent 1960’s were coming to an end, Gaye was reevaluating his concept of music. He was “very much affected by letters my brother was sending me from Vietnam, as well as the social situation here at home.” So Marvin was receptive when Renaldo “Obie” Benson of the Four Tops brought him an untitled song that he was working on after seeing war protestors beaten by the police. Benson did not classify his piece as a protest song, “No man, it’s a love song, about love and understanding. I’m not protesting, I want to know what is going on.”

Gaye added some of his own lyrics and gave the song its title. He went to Barry Gordy at Motown, but Gordy said that it was really a protest song and would be bad for business. When Gaye persisted, Gordy relented because he did not want to offend his star. The single was released in 1971, and it turned out fine for business – the song went to #2 on the pop charts and topped the R&B charts for weeks.

The song is a soulful anthem about war abroad and socio-economic problems at home. Some 48 years later, the lyrics of the song continue to resonate:

We don’t need to escalate

You see, war is not the answer

For only love can conquer hate

Don’t punish me with brutality

C’mon talk to me

So you can see me

What’s going on

Listen here.