In the last Hot Stove, I began what has turned into a trilogy. The starting point was my first year in politics, 1968, when I met two “Washington Senators” from Missouri, Stuart Symington and Tom Eagleton. At that time, Symington was serving in his third term in the Senate and Eagleton was running for his first. In the last post, you read about Stuart Symington’s aid to the St. Louis Cardinals and the Kansas City Royals. This post (and the next one) will focus on Tom Eagleton’s baseball passion.

Eagleton Source Material: I scoured the internet and Eagleton archives to cherry pick information about Tom Eagleton and baseball. There was a lot more than I thought I would find. He really liked his Cardinals. Unless otherwise noted below, the italicized quotes are from Tom’s own words. For those who knew him, you will likely start hearing his distinctive raspy voice.

I also got background material from the 2011 biography Call me Tom by James Giglio. As the book title suggests, those who dealt with Senator Eagleton over a period of time were asked by him to please just call him Tom. That was hard to do for most of us who felt more natural calling him Senator, but as the years went by, it became comfortable to do what he said. So I will sometimes lapse into Tom in this post, but never to suggest any lack of respect. As you will see, Tom was slower to apply that rule for himself when it came to Gussie Busch.

The Cardinals and Young Tom Eagleton: Tom Eagleton grew up with the Cardinals. His father Mark was a fan at least since the Dizzy Dean/Gashouse Gang days in the 1930’s. The Cardinals were part of the family DNA.

“As we were growing up, the male Eagletons were fast eaters or ‘gulpers.’ My father and brother [Mark Jr.] would quickly finish their meals and head for the living room to discuss (or argue) one of the ‘matters of the day.’ I would catch up as quickly as I could. My father selected the subject matter, usually from the newspapers, e.g. world events and leaders, especially the threat of World War II; Cardinals baseball; bank robbers like John Dillinger and ‘Ma’ Barker; Ireland; politics…Frequently, we argued so much that without knowing it switched sides to keep the argument going. That is where I first became interested in politics.”

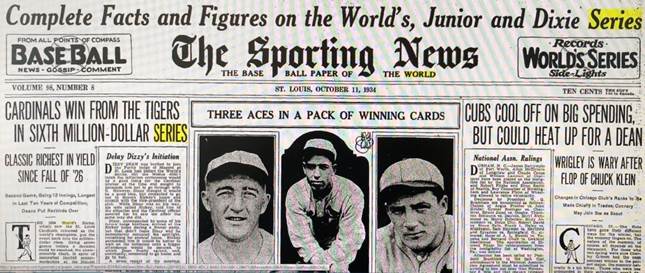

The Eagleton household purchased the weekly Sporting News, the national “Bible of Baseball” that was published in St. Louis. Below, from the front page on the Cards winning the 1934 World Series.

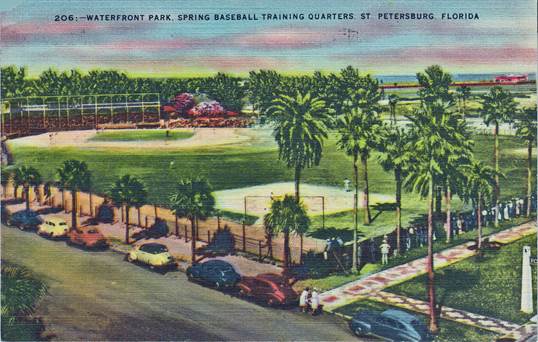

Starting in 1937, when young Tom would have been seven, the family annually went to spring training. The first year was in Daytona, and then St. Petersburg became the long-time spring home for the Cardinals. From 1943 to 1945, because of wartime travel restrictions, the team trained in Cairo, Illinois.

“Every spring, my father took Mark and me out of CDS for three weeks to go to the training camp of the St. Louis Cardinals…Mother was dragooned. She didn’t abhor baseball but she sure didn’t love it the way we did…Mark and I went to a private school until 12 noon, then a taxi took us all to the rickety old wooden Al Lang Field where the Cardinals played…We stayed with the Cardinal players at the decidedly unglamorous Bainbridge Hotel…In the evening, we would sit in front of the hotel and listen to the players talk. ‘Pepper’ Martin was our favorite. He was a comedian, a juggler, and a pseudo-dancer. At 7:00 p.m., we went to our room and studied until 9:30 p.m. under the tutelage of our mother. A bingo event was held one night a week. Howard Krist, a Cardinals relief pitcher, ran the event; I picked the balls out of the basket and announced the numbers – my first experience with public speaking.”

[Spring Training Stadium Trivia: The quote above refers to a rickety Al Lang Field, but Tom was likely referring to Waterfront Park which was demolished in 1947 and replaced at the same location by Al Lang Stadium.]

Branch Rickey was the general manager of the Cardinals from 1919 to 1942. He built the first major league farm system and made the Cardinals the class of the National League with the Gashouse Gang in the 1930’s and pennant winners in the 1940’s with players he developed before moving on to the Dodgers in 1943. Eagleton recalled Rickey from those spring training years:

“The players were ‘broker than broke.’ Branch Rickey, the general manager, strongly believed in the minimum wage for baseball players…Every spring training, Rickey gave a sermon at the biggest Protestant church in downtown St. Petersburg. Thrift was frequently interspersed in his remarks. Every player was ‘invited’ to attend. They all came and so did we. Rickey was a mesmerizing orator, with a great voice and a Clintonesque style of using scripture. He collapsed and died while giving a speech – for me, that’s the way to go.”

In the early 1940’s, Eagleton got a first look at future Hall of Famer Stan Musial. George Vecsey, in his bio Stan Musial: An American Life, has a Musial quote from 1976: “I’m a Democrat. Tom Eagleton, the Senator, tells me he remembers sitting in my lap when he was a kid visiting our spring training camp years ago.” Below, at spring training in 1942, Cardinal manager Billy Southworth and 21-year-old Stan Musial.

In high school, Tom played first base on the varsity team. As recounted in James Giglio’s bio, Tom was a “fine fielder, a mediocre hitter, and slow afoot…played on a dismal team…enjoyed the game more than anybody else on the field.” Tom quipped, “I could catch ground balls …about 50 percent of the time, if they were hit directly at me. My range was two feet either way. As a hitter, I could hit a slow pitch down the middle. Anything else was a pitiful swing and a miss.”

Tom was 17-years-old when former Cardinals GM Branch Rickey integrated major league baseball in 1947.

“I recall the first season that Jackie Robinson broke in with the Brooklyn Dodgers and played in St. Louis. The biggest racist on the baseball Cardinals was Enos ‘Country’ Slaughter, the enormously popular right fielder. In one game, I saw Slaughter running to second base, but instead of sliding into the bag, he flew through the air trying to spike Robinson in his ankles. One could feel the tension and anxiety of the moment.”

“Every summer we drove to our second home in Douglas, Michigan…Our black cook went with us and my dad had to call…AAA…to find which gasoline stations would allow blacks to use the restrooms. I also remember going to ball games at old Sportsman’s Park where blacks were allowed to sit only in the right field ‘pavilion’ behind a screen. As a youngster, I simply accepted all of this as part of American life. As I matured, I began to realize the horrors of segregation.”

[Jim Crow Trivia: Mark Eagleton’s call to AAA had a parallel for African-Americans who were “traveling while black” and wanted to have a “vacation without aggravation.” First published in 1936, The Negro Motorist Green Book listed hotels, vacation venues, restaurants, filling stations and other businesses where African-Americans were accepted as customers. The book was not limited to the south – it had entries for all states. This is the subject of the new movie Green Book. More on that below in Lonnie’s Jukebox.]

Gussie Busch and the Cardinals: Anheuser-Busch has roots in St. Louis going back to 1852. August A. “Gussie” Busch, Jr. joined the family business during Prohibition when “near beer” was barely keeping the brewery alive. An early indication of his sales genius came from a gift he gave his father in celebration of the end of Prohibition in 1933 – a grand beer wagon drawn by a team of Clydesdales. Realizing the potential for promotion, the Clydesdales were taken around the country, including a trip down Pennsylvania Avenue to deliver a case of Budweiser to President Roosevelt at the White House (below). Gussie became president of the company in 1946.

Tom Eagleton’s father Mark and Gussie Busch were friends, and Anheuser-Busch became a client of Mark Eagleton’s law firm. That work was later expanded to include the Cardinals after the company purchased the team in 1953. The prior owner Fred Saigh had been indicted on income tax evasion charges and needed to sell the team. Busch convinced the company to buy the Cardinals – both as a way to market the company beer products and as a civic gesture to keep the team in St. Louis. The company also bought Sportsman’s Park from the St. Louis Browns. Busch soon changed the park’s name to Busch Stadium and added a neon Anheuser-Busch eagle with flapping wings to the scoreboard.

Coincidentally, Mark Eagleton had already given a helping hand to the Cardinals. Two years before Busch bought the team, Stan Musial convinced owner Fred Saigh to raise Musial’s salary to $75,000 for the 1951 season. The problem was that this was in potential violation of the anti-inflationary rules of the Wage Stabilization Board established for the Korean War. Saigh sought an exemption so he could pay Musial the full raise, but he was turned down. While an appeal was still pending in early 1952, Musial ran into Secretary of Labor Maurice Tobin at a baseball dinner in Boston. Baseball fan Tobin suggested that Musial bring his attorney with him to Washington to meet with Tobin and the Board. Musial did and got a favorable decision. The attorney he brought was Mark Eagleton.

The Cardinals and Integration: When Jackie Robinson arrived in 1947, many Cardinal players threatened to strike rather than play on the same field as Robinson. National League President Ford Frick took a hard stance and said he would suspend the players. The players backed down on the strike, but the team heard the message – there would be no black players in the Cardinal locker room. This was also a reflection of the city, then the southernmost franchise in the majors. Jackie Robinson told Roger Kahn in The Boys of Summer that he and fellow black players were jeered everywhere in the league, but nowhere worse than St. Louis.

In a New York Times article in 2009, sportswriter George Vecsey reminisced with Don Newcombe, a black teammate of Robinson on the Dodgers. Newcombe remembered being at a game in St. Louis in 1949 or 1950, and thousands of black fans were milling around the street, unable to pay their way into the game because the outfield pavilion, where blacks had been confined, was sold out. Supposedly, the stands had been legally integrated a few years earlier, but many of Robinson’s fans knew they were not welcome.

Newcombe recalled that “Jackie looked out and saw a bunch of people in the street with radios on” and summoned Burt Shotton, the Dodgers manager, who said, “I never saw anything like this.” The Cardinals were informed that the Dodgers would not take the field until the fans were inside. The Cardinals relented and pocketed extra money for the day. Newcombe: “We just wanted them to watch us play, not stand out in the street with radios.”

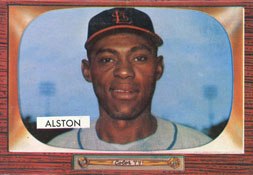

When Anheuser-Busch bought the team in 1953 and Gussie Busch found out there were no black players, he said, “How can it be the great American game if blacks can’t play.” He also knew that Budweiser was the top selling beer among black customers. Busch quickly went to work on the issue, and on opening day in 1954, the Cards had their first black player, starting first baseman Tom Alston.

It took a while to trade for and develop black players, but the reputation for diversity grew and many greats ended up in St. Louis. Lou Brock, Bob Gibson, Curt Flood, Bill White and others were integral to the World Championships that followed.

Tom and Gussie: When Tom Eagleton graduated from Harvard Law School in 1954, he joined his father’s firm and soon found himself working regularly at the legal department at the brewery.

“Eventually I became, without a title, August A. Busch, Jr.’s assistant and sometimes lawyer. Mr. Busch, the head of the brewery, was popularly known as ‘Gussie,’ but even after I became a senator he was always ‘Mr. Busch’ to me out of great admiration and respect. Gussie was extraordinarily popular with his employees. He was a blue-collar-worker’s CEO. He had a gravelly voice, a short fuse and was a Knute Rockne/Casey Stengel, off-the-cuff speaker with the enthusiasm and persuasiveness of Lee Iacocca.”

Eagleton often traveled with Busch in the company’s private silver railroad car. Busch did not like to fly and so used the rail car to travel the country and give sales and pep talks to wholesalers. “Gussie always traveled with an entourage that included a sufficient number (four) to play ‘Gin and Honors’…I was selected for these trips, as a lawyer who could play a decent game of his Gussie-type gin rummy…lots of special rules and precedents – all of which were instantaneously promulgated by Busch over the years of gin rummy combat…In a given evening, he would announce a new rule – always in his favor. Arguments were loud, intense and often prolonged. The truth is, Busch loved the arguments as much as the game. It was all part of the combat of life in which winning beat the hell out of losing.”

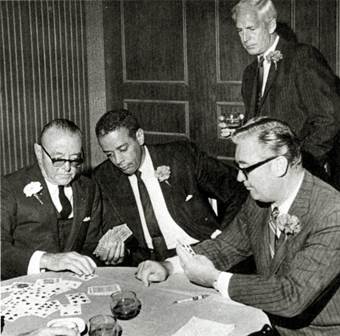

Gin rummy continued through the years for Busch. Below, in 1969 before a baseball dinner, Busch is on the left with his chauffer holding his cards because Busch had a broken finger. The other gin player is Cardinal broadcaster Harry Caray. Another broadcaster, Jack Buck, is standing behind Caray.

The trips on the train sometimes included Washington, DC, where “we were once joined for dinner by Majority Leader Senator Lyndon B. Johnson, House Speaker Sam Rayburn, Senator Stuart Symington, Congressman Dick Bolling of Kansas City, and Supreme Court Justice Tom Clark. Gussie did not go to them. They came to him.” Mark Eagleton had met Tom Clark on a couple of visits on President Truman’s yacht when Clark was in the famous poker games. Clark was a big baseball fan and attended some Cardinals spring training games with Mark and his sons. Tom had the opportunity to clerk for Justice Clark when he graduated from Harvard, but chose to return to St. Louis. Gussie’s politics had a practical side. Eagleton said Busch was a “repeal of Prohibition” Democrat.

“On one segment of our nationwide travels, a man named Bob Baskowitz joined us. Baskowitz sold all of the beer bottles to A-B. We rotated partners in this ‘gin and honors’ game. I won a hand with a ‘quick knock’ and got up to stand behind my partner, Baskowitz, and watch. He had three kings and threw one of them as a discard – an intentional mistake. He got up to go to the toilet and I followed him. I said ‘Mr. Baskowitz, you did a tank job…You are my partner. You can throw away your money to kiss Mr. Busch’s ass, but you cannot throw away my money.’ Baskowitz responded, ‘Tom, can’t you understand Gussie loves to win and I love to make him happy.’”

In Eagleton’s last train trip as a brewery lawyer, he won some money at the gin table. “As the trip ended, my fiancée, Barbara Smith, met me at the old Delmar station. Gussie came out, kissed her, and said ‘He’s rich. Make him buy you a big diamond ring.’ That was pretty much the end of my formal business association with a warm, wonderful friend, Gussie Busch, and of the first part of my political education. Soon, I would be ready to tip-toe into the world of real politics.”

Early Politics: When Tom was a boy having post-dinner discussions with his father about politics and baseball, Mark Eagleton was a Bull Moose Republican in the progressive style of Theodore Roosevelt. He was elected in 1937 to serve as a Republican member of the St. Louis Board of Education. He took his son Tom to the Republican Convention in 1940 where they met Wendell Willkie (the eventual nominee), Robert Taft and Thomas Dewey. The 11-year-old Tom was for Dewey “because he was handing out more buttons and horns and hats.” When the Republicans failed to re-nominate Willkie in 1944, Mark Eagleton left the party and supported Franklin Roosevelt. In 1946, he arranged for Tom, then in high school, to attend what became known as Winston Churchill’s “Iron Curtain” speech in Fulton, Missouri (photo below). Later in life, Tom said that “I always say the two best speakers I ever heard were [Branch] Rickey and Winston Churchill.”

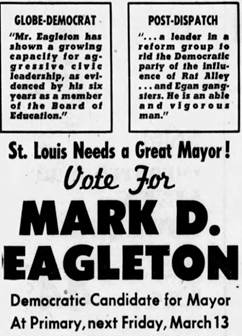

In 1953, Mark Eagleton was a candidate in the Democratic primary race for mayor. He lost.

His son Tom never lost an election. At age 27 in 1956, Tom Eagleton was elected circuit attorney of St. Louis. In 1960, he ran statewide and became the youngest attorney general in the country.

As AG, Tom was required by law to live in Jefferson City. This was not his favorite place, so he ran for Lt. Governor in 1964. He won and now could be based in St. Louis. The LG office had the additional advantage of being part-time. So he could again practice law, and I ran across a case that showed he did just that. And no surprise, the client was Gussie Busch who had been sued by Fred Saigh, the man who sold the Cardinals to Anheuser-Busch.

1964 – World Series: After Saigh served his prison time for tax evasion, he became a major holder of Anheuser-Busch stock. He was also a vocal critic of Gussie Busch as the leader of the Cardinals. During the 1964 season, Saigh claimed the team was demoralized. On August 16, with the Cardinals some 10 games behind the Phillies, Busch fired GM Bing Devine. On August 20, Saigh released a public letter offering to buy the team back. I’ll let Tom Eagleton tell the next part of this story (taken from his speech on the Senate floor in 1977 honoring Lou Brock’s career base-stealing record):

“As a Cardinals fan, I well remember the season of 1964. It was a year of triumph for the Cardinals, as they sneaked past the Philadelphia Phillies on the last day of the season to win the pennant, and then went on to defeat the New York Yankees in a thrilling seven-game World Series. It was a glorious October in St. Louis, but it might never have happened except for the events of the previous June. It was in June of 1964 that the Cardinals made one of the most controversial trades, a trade about which even General Manager Bing Devine had reservations. The deal saw the Cardinals trading their standout pitcher, Ernie Broglio, to the Chicago Cubs in exchange for an unproven young outfielder named Lou Brock.”

It was the first World Series win for the Cardinals in the Gussie Busch era. Fred Saigh’s offer to repurchase the team was, let’s say, untimely. But Saigh was not done with Gussie. He brought a claim as a company shareholder claiming that Gussie had been given favorable stock options that were unfair to other shareholders. The case went all the way to the Missouri Supreme Court, and Gussie won in a 1966 decision. The first two lawyers listed in the appeal as representing Gussie were Mark Eagleton and his son Tom.

1968 – The First Race for the Senate: By 1968, Eagleton was ready for the bigger stage of Washington, DC. – the U. S. Senate. Incumbent Ed Long had most of the Democratic establishment support, but was considered vulnerable. Another candidate, wealthy businessman True Davis, was also in the race. Some thought it was too early for Tom to make the jump.

“The closest I came to being talked out of it was when Gussie Busch called and asked if I could come to see him. I knew why. Mr. Busch was a great man. I had worked for him. In his gravelly voice, he asked me not to run: ‘Tom, I’m with Ed Long. You are smarter than him. I know that, but you are young. Symington can’t live forever and I promise I will support you when he runs out of gas, which can’t be all that far away.’” [As it played out, Stuart Symington won his fourth term in 1970 and so his seat was not open until 1976.]

“I paused for a while and then said ‘Mr. Busch, you know what I think of you…I simply have to move up or out of politics. I cannot bear another term of Lt. Governor. It’s close to a nothing job. If I run and lose, I am still at an age where I can have a new life practicing law or teaching or working with you again.’ He responded: ‘I knew your answer. I simply had to try. It will break my heart to be against you, but I will have to be. We are friends and if you win the primary, I will go all out for you.’”

I met Tom Eagleton during that 1968 campaign when he appeared as a speaker at our Young Democrats club. The YD club worked closely with the Committee for County Progress, a Jackson County reform organization that put together a ticket that won almost all county offices. The CCP also made a crucial endorsement of Eagleton in the hotly contested Senate primary race. The charismatic candidate became a favorite of our Young Democrats group. Eagleton won the close 3-way primary and moved on to the general election.

In October, Eagleton’s St. Louis Cardinals returned to the World Series. They had won the Series in 1967, but the Detroit Tigers took the 1968 title in an gripping seven-game series.

Eagleton had better luck than his Cardinals. In November, he won the general election and became a U. S. Senator at age 39.

Stay Tuned: My next post, Hot Stove #89, will feature more on Eagleton and baseball. Teasers: Stan Musial, Howard Cosell and the 1985 I-70 World Series starring Don Denkinger.

Lonnie’s Jukebox: In a long weekend before Thanksgiving, Rita and I binged on six Broadway shows in New York. Top of the list: To Kill a Mockingbird, written for the stage by Aaron Sorkin (West Wing, Moneyball, etc.) and starring Jeff Daniels as Atticus Finch. Next favorite: The New One, a one-man show by standup comedian Mike Birbiglia. Very funny. Network with Bryan Cranston is in previews – he was good, but some of the other actors need some more work before the official opening night.

In movie news, we just saw Green Book, a road trip film inspired by a true story. We give it two thumbs-up. Mahershala Ali plays an African-American piano virtuoso on a 1962 tour of the Midwest and Deep South. House of Cards fans will know Ali as the cool lobbyist Remy. He also won an Oscar for Moonlight. His driver/bodyguard for the trip is a streetwise Italian-American played by Viggo Mortensen. They often consult The Negro Motorist Green Book to determine where they will be welcome to eat and sleep on the road. Potential Oscar nominations for both actors. And for vintage car fans, a real feast.

For baseball fans, I want to give one more plug for Bohemian Rhapsody, the biopic on Queen. One of the most common anthems played between innings is Queen’s “We Will Rock You” – the one with the rhythmic two stomps and a clap, a call and response song that engages the crowd. After you see the movie, you will gain a new perspective for the next time you hear (and participate in) the song at a stadium. The movie has become a big hit. The box office gross is now over $150 million in the U. S. and approaching $500 million worldwide. Whether you see the movie or not, don’t miss the original 1985 concert footage from Live Aid, one of the biggest moments (well, 24 minutes) in rock ‘n’ roll history. Click here.

To finish this post, I looked for a song to go with the Cardinals win in the 1964 World Series. A natural choice might be to stick with Queen and play “We Are the Champions.” But Queen already has a lot of ink in this post and the song did not come out until 1977. So I’ll go with a record from 1964, the title of which describes what Cardinal fans were doing after their team beat the Yankees in Game 7. Click here.