Rita and I have just returned from Eastern Europe. The primary purpose of our journey was to visit the homeland of my grandparents – to breathe the air of my ancestors. My fraternal grandparents (Shalton, as Americanized) were from a village near Vilnius, Lithuania, and my maternal grandparents (Lukomski) were from a village near Lviv, Ukraine. They came to the states in 1907 and 1911. They didn’t speak English and had no money or special skills. Just dreamers with a willingness to work hard and become patriotic Americans. They are my heroes.

We also wanted to cross paths with friends who were going to be in Riga, Latvia, as well as see Krakow, Poland. Rita found an organized group bus tour that would take us from Riga to Vilnius to Warsaw to Krakow. We then finished by flying to Lviv.

There are historical parallels in the five cities. Each has a central old town of cobblestone streets, medieval-era architecture and a lively main square. They are in countries that have for centuries been invaded, occupied and placed within arbitrary borders drawn by the victors. They were all invaded in World War II by the Nazis who wiped out the Jewish populations. Then came the Russians who “liberated” each country with a brutal occupation and forced membership in the U.S.S.R. or as a “satellite state” controlled by the Soviets. The people who resisted were killed, imprisoned, exiled or sent to Siberia.

The good news is that all of the countries eventually regained their independence. The resilience of the people and the desire to maintain their culture is inspiring. But the cloud of Russia remains, as most evident today in the covert war on the eastern side of Ukraine and the occupation of Crimea. By coincidence, we returned on a flight via Helsinki, two days before the Trump/Putin summit in that city. That’s all I’ll say about that.

Riga, Latvia: We met up with Anne Devaney and Talis Bergmanis. Anne and Rita have been best friends since grade school, and Talis joins me in Baltic ancestry (he is Latvian to my Lithuanian). They were in Riga for the song and dance festival held every five years since 1873. Thousands gather from all over Latvia to participate at venues spread throughout the city. Many are free events in the parks, and the city fills up with performers in folk costumes. It was a joyous and festive atmosphere.

We also joined up with our bus group to see several tourist sites in Riga. Outside the medieval old town, Riga features what may be the largest collection of Art Nouveau buildings in the world. The decorative facades are stunning. Many were designed by renowned Jewish architect Mikhail Eisenstein, including this favorite of Rita’s with the faces at the top:

4th of July: It was time to hit the road with our bus group and so we left Riga for Vilnius. At a rest stop in rural Lithuania, we got a nice surprise from our guide Ieva. A picnic and sparklers to celebrate the 4th of July.

Vilnius, Lithuania: My dad’s parents left Lithuania and entered the states through Ellis Island in 1907. We don’t have a good record of the original Lithuanian name nor do we know the name of the home village near Vilnius. So I had no genealogy prospects. But it was still a thrill to be in their old country. Assuming they were ever in Vilnius to visit, the old town center is like it was in 1907.

Vilnius was fortified with a wall and ten city gates in the early 1500’s. Only one gate (the “Gate of Dawn”) remains, and it now holds a chapel – note the priest in the photo:

We toured the Museum of Occupations and Freedom Fights housed in a building once used by the Gestapo and the KGB as offices and a prison. The primary focus is on the 50-year Russian occupation that finally ended with independence in 1991. The tour includes the torture and execution rooms, and the exhibits chronicle the atrocities of the arrests, deportations, executions, forced-labor camps and Siberian exile.

The Russians did all they could to dilute Lithuanian nationalism. But thankfully the culture held and a proud nation is in place today. All three Baltic nations (Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania) have shed the dreary Soviet days and are now members of NATO and the European Union.

Below, Rita and I at the Lithuanian border just before we head into Poland.

Warsaw, Poland: Warsaw took some of the hardest hits in World War II – 85% of the city was in rubble. Remarkably, the citizens of the country taxed themselves to rebuild the city to look like it had before the destruction – and it was mostly completed by 1955. The result is most impressive.

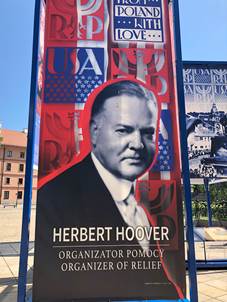

Along a wide plaza near the Presidential Palace, there was an exhibit commemorating the “Polish Declaration of Admiration and Friendship of the United States.” In 1926, the signatures of some 5.5 million Poles were collected in 111 volumes and presented to President Calvin Coolidge. This was a thank you for the relief operation mounted by the U.S. after World War I to save millions of Europeans from starvation. The relief effort was led by future president Herbert Hoover. The Declaration was timed to also celebrate the 150th anniversary of the 4th of July. Poland was still bracketed by unstable neighbors Germany and Russia, and sure enough, Poland was a repeat victim in World War II. The U.S. again came to the rescue, and President Harry Truman tapped now-former President Hoover to again assist war-devastated Europe.

There was also a U.S./Poland foreign exchange event in a nearby park. There were lots of American flags and booths, plus some life size cutouts of Elvis Presley, Marilyn Monroe and Donald and Melania Trump. I chose Elvis for my photo op.

Frederic Chopin – In Two Parts: The Polish composer is revered in his home country. The Warsaw airport is named after him, and there is a monumental statue of him in a Warsaw park. But this statue is a replica. The Nazis blew up the original in 1940 (I’ll just say it once, but the proof was in every city we visited. There are no good Nazis or neo-Nazis).

We also went to the Holy Cross Church in Warsaw where Chopin’s heart is entombed in a stone pillar. We thought we had already seen the resting place for all of Chopin when we visited the famous Pere Lachaise Cemetery in Paris in 2010. Chopin is there with many notables, including Oscar Wilde, Edith Piaf and Jim Morrison of the Doors. Chopin had moved to Paris in 1831 and never returned to Poland. But he left instructions that his heart be removed after his death and returned to his homeland. So now Rita and I have been to the final resting places for all of Chopin.

Czeslaw Bielecki: In my last post, I listed the cities that Rita and I planned to visit on our trip. When Hot Stove reader Jon Copaken saw that we would be in Warsaw, he emailed to say I should get together with his friend – architect Czeslaw Bielecki. While on summer break from Michigan Business School in 1992, Jon had interned for Czeslaw in Warsaw. He thought I would find meeting with Czeslaw to be an “amazing intellectual experience.” Oh my, yes it was.

From 1945 to 1989, Poland was under Soviet dominance as a communist country. In 1980, after years of economic problems, repression and strikes, the independent trade union “Solidarity” was formed under the leadership of electrician Lech Walesa. In 1981, the government declared martial law, and Walesa and other Solidarity leaders and activists were jailed. Solidarity was outlawed in late 1982, but the effort continued through the mid-1980’s with underground activities, including the publication of a weekly newspaper. The publisher of that underground paper was Czeslaw Bielecki.

Though his Jewish parents had left Poland during the anti-Semitic campaign of 1968, Czeslaw stayed on as a freedom activist. At age 20, he participated in the 1968 pro-democracy demonstrations and then in the 1970’s in other nonviolent activities. He became part of the Solidarity movement, working as the publishing head of CDN (an acronym for “To Be Continued”), a large underground publishing house that covertly printed books, leaflets and pamphlets plus a newspaper with a circulation of 125,000. Under a pen name, he wrote a series of political essays assessing the Polish struggle and what action should be taken.

On April 13, 1985, the 37-year old Czeslaw was arrested, beaten and placed in the prison hospital. He was charged with treason. His total jail time was about two years, and his imprisonment got international notice. In the New York Times on March 1, 1986, it was reported that Czeslaw and four other prisoners were in the midst of a 4-month hunger strike and being force-fed to keep them alive. One of the purposes of Czeslaw’s hunger strike was to get permission to see his two small children and his father. He lost 70 pounds.

Through all this, he wrote essays that were smuggled out of the prison and circulated. On March 27, 1986, while still on his hunger strike, the New York Review of Books published one of the smuggled essays – a “Monologue” about his life in jail. The title referred to his decision to not speak to his interrogators, hence the monologue. For more on Czeslaw’s publishing and activism, I refer you to an excellent series of interview videos and transcripts in The Freedom Collection at the George W. Bush Institute.

With some help from the West (including the CIA and AFL/CIO) and support from the Krakow bishop who had become Pope John Paul II in 1978, Solidarity ultimately got its victory. A Solidarity-led parliament was elected in 1989, and Lech Walesa was elected president in 1990. Czeslaw served as an advisor to Walesa from 1990 to 1995 and was a member of parliament from 1997 to 2001.

Before, during and after his activism, Czeslaw was (and is) a successful architect and writer. The scope of his work is extensive as can be seen on his website. The project that Rita and I got to see is clearly one of his favorites – his home in the countryside near the small town of Bartoszowka. Czeslaw picked us up at our Warsaw hotel, and after the half-hour ride, this is what we saw:

The home features stone arcades constructed from hand-cracked field boulders (helping the stonemason do this back in 1992 was the intern Jon Copaken). The interior is uniquely decorated and features many pieces from Polish artists. The house is surrounded by extensive gardens (an English garden and another in Far Eastern style) and a series of ponds for fish and ducks. There is a commercial size blueberry patch. It is an idyllic setting.

We set up shop on the outside terrace connecting the two wings of the house. Grandchildren made fleeting appearances. We were treated to dinner by his partner, Ilona Lepkowski, a well-known movie and TV screenwriter. The meal was topped off with a liqueur made from fruit grown in his gardens.

But the biggest treat was the conversation. Not quite a monologue, but Rita and I were most happy to listen. And he often tested us with his opinions. It was way more than just the revolution. Some of the topics: his writings, politics today in Poland, Israel and Russia, Trump, immigration (and its effect on culture in Europe), how to run a business (his own and his son’s restaurants), the #MeToo movement, Roman Polanski, the Polish movie In Darkness that Rita and I had seen at the Telluride Film Festival in 2011, his novel (not biography) about a jailed dissident in a communist country, Frank Gehry’s “Fred and Ginger” building in Prague, the Art Nouveau buildings we had seen in Riga, and on and on. Rita described it as our own personal TED Talk.

I told him that his smuggling of his writings out of the Warsaw prison reminded me of Martin Luther King doing this with the Letter from the Birmingham Jail.

Our conversation lasted a total of five hours, but went by way too fast.

Below, Czeslaw showing us a potential new project for a memorial commemorating the decisive victory of the Poles over the invading Russian Bolsheviks in 1920.

As I reflected later, it occurred to me that Czeslaw could be called the Thomas Jefferson of Poland. A revolutionary. A writer for the cause. An aide to a president. An office holder. An architect, including for his own home (as in Monticello). A gardener. A wine (liqueur) maker. A philosopher. I emailed this idea to Czeslaw, but he demurred, thinking I might be exaggerating and possibly not objective. I probably have some favoritism – I never got to spend five hours with Thomas Jefferson. But I like my idea.

On the Road: After we left Warsaw, our bus made two stops before reaching Krakow. The first was at the Jasna Gora Monastery in Czestochowa, the home of the “Black Madonna” icon which is widely venerated and credited with many miracles. The monastery dates back to 1382 and is the third largest Catholic pilgrimage site in the world. The mix of tourists and pilgrims makes for a Disneyland size crowd. There was a Mass going on in the packed church and another for a gigantic crowd on a hillside outside the church.

Fortunately, we were set up with Father Simon as our guide, and he knew all the back ways into the church and other parts of the complex. Father Simon was destined to be either a priest or a stand-up comic. He swiftly worked us through the crowds with one-liners. He said one of the miracles attributed to the Black Madonna was the turning back of the invading Swedish Army in the 17th century – “now we only fight the Swedes in hockey and soccer.” He told us how to make holy water – “Boil the Hell out of it.” The monastery was impressive, but Father Simon’s shtick will be what I remember.

In a stark contrast, our second stop was the concentration camp in Auschwitz, a sobering experience indeed. But one that is needed so that we never forget or deny.

Krakow, Poland: Although we would not reach Lviv until our next stop, I was already in my homeland based upon the borders that applied when my grandparents left in the early 1900’s. Krakow and Lviv were both in Galicia, a province of what was then Austria-Hungary. The borders of the province were arbitrarily drawn and the western part was mostly Poles, while the east was mostly Ukrainians. After wars and revisions of borders, Krakow became part of Poland and Lviv part of Ukraine.

We reached Krakow in the evening and headed for the town square. It is magnificent – huge, great architecture, outdoor cafes, entertainers, horse carriages – very much alive. It rivals Prague as the best town square in Europe.

The surrounding medieval city is intact in its original form because it was not bombed in World War II. At one edge of the old city are Wawel Castle, once home to the Polish monarchs, and Wawel Cathedral, the church of the bishop of Krakow (from 1964 to 1978, that bishop was Karol Wojtyla who in 1978 became Pope John Paul II).

We toured what was once the vibrant Jewish district of Kazimierz where Helena Rubenstein lived and Oskar Schindler recruited his factory workers. The guide noted that Steven Spielberg used the area for filming shots for Schindler’s List, and he had to clear the area of cars and outside restaurant umbrellas to create a proper historic shot. He also paid residents to remove their TV antennas while he was filming. Schindler’s old factory is gone, but one of his administrative buildings houses a wartime museum.

Ladies with an Ermine: After our bus tour ended, we stayed an extra day in Krakow. We needed more time to absorb the beautiful city plus we had one special thing we did not want to miss – Leonardo da Vinci’s “Lady with an Ermine.” We never pass up a chance to see a da Vinci. Only about 30 of his paintings remain, four of which are portraits of ladies, the “Mona Lisa” being the most famous. But the “Lady with an Ermine” might offer the best story.

The painting dates from about 1490, and the subject was the mistress of the Duke of Milan. The painting left Italy in 1798 after being purchased by a Polish prince. The painting travelled extensively, but was hidden in 1830 to keep it from the invading Russians. The painting stayed with the prince’s family, including during exile in Paris, and it ended up in Krakow in 1882. In 1939, the Germans proved quicker than the 1830 Russians, and the painting was seized by the Nazis. After World War II, it was one of the treasures recovered by the Monuments Men. It now resides in the National Museum in Krakow.

Rita and I had seen the painting in 1992 at an exhibit at the National Gallery in Washington, D.C.: “Circa 1492: Art in the Age of Exploration.” That is, art that was around when Christopher Columbus sailed the ocean blue. But with a new opportunity, we saw it again. Photos are not allowed, but there is a reproduction in the hallway and the museum even provides props. So here are two ladies with an ermine, one a reproduction, the other an original:

Lviv, Ukraine: We flew from Krakow (the “John Paul II” airport) to Lviv. This is the Ukrainian spelling for the city, but during outsider rule, it has also been known as Lvov (Russian), Lwow (Polish) and Lemberg (German). We got some good luck on making contacts in Lviv – my son Brian is friends with a couple who met in Ukraine and now live in Kansas City – the American Tony who had been in Kiev on business, and the Ukrainian Anya, a resident of Lviv attending college in Kiev. Tony and Anya put us in touch with Anya’s aunt Lena who in turn arranged for our guide/driver/translator Natalia. Here are Natalia (left) and Lena with Rita in the hotel lobby:

Look again at that photo. Rita is not winking. She had in infection in her right eye, and the first order of business was to get her to a doctor. Lena tried to get her family doctor. Not in. A nearby clinic, too late, doc gone for the day. So we went to the eye clinic for a hospital not far away. Success, with no waiting time (nor any bill, universal health care), and a quick $6 prescription at the drug store. It all worked and Rita’s eye quickly improved. When we got back to KC, Rita thought she should have it checked. It took longer to get a call back for an appointment than it had taken to get treatment in Lviv. The KC doc also told her that the medicine she got in Lviv was “liquid gold” – after the insurance share is paid in the U.S., the patient still owes $187.

The primary mission on this stop was to get to Rozvadiv, the home village of my Lukomski grandparents. It is 26 miles and 45 minutes from Lviv. This left little time for Lviv, but we did get in a little time after Rita’s doctor visit and then on our third day before catching our plane back to the states.

The old town center of Lviv luckily escaped bombing in the wars. So its charming medieval architecture remains in place. Natalia took us through interesting restaurants, shops and churches. One of the churches had a display with photos of soldiers killed on the eastern front in the “non-war” with Russia (Putin’s response to getting out of Ukraine, “That’s impossible because we are not there.”). This sign was on the outside of that same church:

The #FreeSentsov on the sign relates to the imprisonment of Oleg Sentsov, a Ukrainian filmmaker in a Russian prison on what many believe are fabricated charges of terrorism in his native Crimea. Sentsov is currently on a hunger strike that started on May 14, 2018, protesting the incarceration of 65 Ukrainian political prisoners.

The Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church is mostly active in western Ukraine and has a history of resistance to Russia. After World War II, Stalin ordered that the Greek Catholic church “reunite” with the Kremlin-controlled Russian Orthodox Church. To enforce the action, Ukrainian Catholic priests were beaten, tortured and imprisoned. Church property was confiscated. Many Ukrainian Catholics went underground to practice their religion. For some 43 years, the church was considered the largest banned religious community in the world.

We also climbed to the top of Lviv Castle Hill. The castle is long gone, but you get a good panoramic view of the city:

Another stop in the city was at the Lviv Theatre of Opera and Ballet. Opened in 1900, it is the centerpiece of the old city. I like to think my grandparents saw this before emigrating to America a few years later. The specific location of the building has a special story.

The opera house is built over the Poltva River which once served as the moat for the castle. The river was enclosed in a tunnel in the early 19th century to prevent the spread of malaria. The submerged river is the key channel in Lviv’s labyrinth of tunnels that form the sewer system for the city.

After we toured the beautiful building, Natalia took us to a ground-level side door that leads underground to a restaurant and a small museum about the construction of the opera house. There is also a live-webcam showing the underground river flowing below. Natalia started telling us the story of how a band of Jews hid in the tunnels to escape the Nazis, and it dawned on us that this was the story told in the Polish movie In Darkness (as we had discussed with Czeslaw Bielecki and Ilona Lepkowski). The movie was based on the book In the Sewers of Lvov (the Polish spelling because Lviv was part of Poland as WWII broke out). Two Polish Catholic sewer workers sheltered and fed the group in the tunnels for 14 months – first for money, but when that ran out, because they wanted the Jews to survive.

Rozvadiv, Ukraine: In contrast to the Shalton side of my family, the Lukomski side has some helpful genealogy information. We knew that my grandparents were born in the 1880’s in the small village of Rozvadiv, then part of Galicia in Austria-Hungary. Their first child, my aunt Martha, was also born there.

We also knew that my grandfather Andrew arrived in Galveston in 1907. A few years ago, Rita and I went to the seaport museum and local library in Galveston and located the ship manifest that showed Andrew as a passenger. As entered on the records by an immigration clerk, Andrew gave these answers for the manifest: Age (26), occupation (farm laborer), read/write (no/no), nationality (Galicia), race or people (Ruthenian, an ethnic term of the Greek Catholics of Galicia), money in possession ($10), polygamist (no), anarchist (no), deformed or crippled (no), height (5’6”), hair (blond) and eyes (blue).

Andrew worked his way up the pipeline and ended up in Sugar Creek, Missouri, where there was a strong Eastern European community. He had by then earned enough money to send for this wife and daughter who arrived in 1911 via the port of Baltimore. Their religion of Greek Catholicism followed them, and they became part of a small Greek Catholic congregation that started a church in Sugar Creek in 1910. I went there as a boy and remember well the icons, the Cyrillic script and Ukrainian service (i.e., not Latin). The church was then named St. Joseph Greek Catholic Church, but it is now called St. Luke’s Byzantine Catholic Church.

To the knowledge of our family, we have no long lost relatives in Rozvadiv. But I still wanted to “breathe the air” and maybe find some documents about my ancestors. So Natalia picked us up in the morning at our Lviv hotel and we headed to Rozvadiv. It was Thursday, July 12 – we were not aware that the date was meaningful.

Soon after we came off the highway, it was easy to spot the dome of the church – the only church in this village of about 3,100 people. To our pleasant surprise, there was a Mass in progress for a holy day in honor of St. Peter and St. Paul. My later look at Wikipedia filled in some blanks. The “Feast of Saints Peter and Paul” falls on June 29 for those churches following the traditional Julian calendar – but that makes it July 12 on the Gregorian calendar. It is a day of “recommended attendance,” and the church was not only full, there were at least a hundred parishioners outside taking part in the Mass. The sound system outside was excellent.

After the Mass was over and the church emptied out, we went in. There were still about 30 parishioners, and it turned out there was to be a 15 minute liturgy for the recently deceased. As we listened to the priest and an amazing 3-person male choir, we marveled at the interior of the church. I really can’t find enough superlatives to describe the icon wall, the paintings, the murals on the ceiling, etc. Amazing craftsmanship down to every detail. I took a 4-minute video of the interior of the church during the liturgy (click here, and be patient, the first 20 seconds show the back of a chair).

The church was built in 1861 – so it would be the church attended by my grandparents. We were told that Franz Joseph, Emperor of Austria-Hungry, appreciated the welcome he got when he traveled through Rozvadiv and so asked a patron to provide funds for a nice church. And the patron did, and to this day is recognized with a coat of arms on the front of the church (see the “W” below). The church has recently been restored.

After the liturgy, we met with the priest, Father Bogdan Kolibek (this is an English attempt to translate the Cyrillic spelling of his name). For the last 40 years, he has led this Church of the Resurrection of Jesus Christ. It is a Ukrainian Greek Catholic church, part of the Byzantine Rite and in “full communion” with the Holy See of the Roman church (in contrast to Eastern Orthodox which is not). But some of the rules are different. Most notably, celibacy. Father Kolibek is married and has five children.

We walked to his home about a block away and had about a half hour talk with him (via our translator Natalia) while he worked the phone to set up a meeting with the church historian who was at work in a nearby village. We also met his wife who was busy in the next room working on the wedding of their son scheduled for the next day. Father Kolibek liked Rita’s hat and Natalia translated to us that he thought we were good people even though I had long ago strayed from my Greek Catholic roots. I asked if he had a history of the church, and he gave us a pamphlet that had been prepared for the 150th anniversary in 2011. It’s in Ukrainian, but nice photos.

We were then joined by our next Good Samaritan, Roman Skolozdra (sp?), who we found was a true historian of everything about the church and the village. As was the case with Father Kolibek, Roman spoke little English, but the wonderful Natalia kept things moving. We were quite lucky that Roman was able to take off work early because it was a holy day. Otherwise, this story would stop here. My thanks to St. Peter and St. Paul for the July 12 timing.

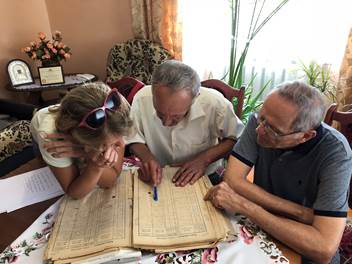

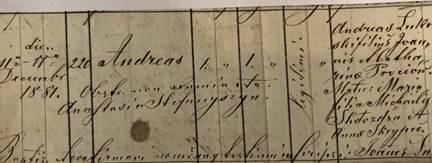

We drove over to Roman’s home, and he proudly showed us his extensive library. He pointed to a stack of about ten ledger books which held the history of the church going back to the 1700’s, even before the current church was built. Each book had three sections – births, marriages and deaths – with handwritten entries (in Latin in the older ones) made at or about the time of each event.

He pulled out the volume that would cover my aunt Martha’s birthday. The pages were like old parchment and were loose from their binding. He rather quickly found Martha’s birth, and I must say I got emotional seeing that recorded piece of history about my family. It showed the date, her address and the names of the midwife, parents and godparents.

I had what I thought were the birthdates of my grandparents, but they did not match up with the records. Also, he had to be careful that he got the right Lukomski branch – the name, with variations in the spelling, was relatively common from about three centuries ago. There are even current residents in Rozvadiv with similar names, but not believed to be related to my family.

We took a lunch break and then came back to try again. Roman was relentless and wanted the answer as much as we did. He methodically checked several months before and after the potential dates and EUREKA, he found both of them. All four of us in the room were ecstatic. Here is part of the Andrew (Andreas) entry from December 11, 1881:

By then, we had put in about three hours and pumped Roman for all sorts of information. He was passionate about the history and insisted on taking us to a field that was once the farm of some Lukomski branch. We also went to the address shown on Martha’s birth notice, her mother’s address. The old home is gone, but the person living in the current house was named Lucik, my grandmother’s maiden name. But again, lots of similar names out there and unknown on any family connection. We also went to the cemetery and took photos of “Lukomski” gravestones (different spellings).

Our total time in Rozvadiv was about eight hours. But more than a century of memories. Father Kolibek and Roman could not have been more gracious, and Natalia was a trooper as our translator. The next day, Roman called Natalia to say he stayed up all night to work back our family tree for some more generations. We did not have time to get back to Rozvadiv – had to catch a plane – but this story is not over.

One last trip photo. We saw a lot of white storks during our trip, both on the ground and in their high nests. These were next to the church in Rozvadiv:

Epilogue: Andrew and Anna Lukomski had nine more children after moving to the states. One was my mom Katie who was born in 1921. The lone survivor of the children is my aunt Ellen who is 94. We are now in a fifth generation of Americans who have benefitted from our courageous immigrant ancestors. Below, from about 1925, with the first nine children and a family friend.

Lonnie’s Jukebox – “Back in the U.S.S.R.”: As readers have likely guessed by now, the golden oldie for this post is “Back in the U.S.S.R.” – the first cut on the Beatles’ White Album. When the song was released in 1968, there was pushback from right-wingers, including the John Birch Society, who said the song promoted communism. This was laughed off by Paul McCartney who reminded everyone that the Beatles and other rock ‘n’ rollers were considered propaganda and banned from the air in Russia in those days.

It was actually a parody of Chuck Berry’s “Back in the USA” and the Beach Boys “California Girls.” McCartney: “It’s tongue in cheek. This is a traveling Russkie who has just flown in from Miami Beach…can’t wait to get back to the Georgian mountains: ‘Georgia’s always on my mind’…I remember singing it in my Jerry Lee Lewis voice.” McCartney’s Russkie is also glad to return home where “the Ukraine girls really knock me out” and the “Moscow girls make me sing and shout.”

Even the Kremlin could not hold back the tide of rock ‘n’ roll. The music came in underground and eventually became legal. In 2003, Paul McCartney played Moscow. When President Putin admitted to being a Beatles fan, one reporter wrote “In this brief moment, Putin wasn’t the arguably despotic ex-KGB officer who’s now regularly accused of violently suppressing political opposition, ignoring human right obligations, and unlawfully annexing half of Ukraine.” For more on this subject and two great videos of McCartney in Red Square singing “Back in the U.S.S.R.” and “Hey Jude,”, click here. Don’t miss Putin in the first 15 seconds of the U.S.S.R. clip.

Poetic Justice: During our trip, Croatia beat Russia in the World Cup.