As we enjoy the return of Veep and Fargo and patiently await the Royals batters…

The Wall Street Journal may seem like an unlikely source of baseball nostalgia and trivia, but here are some items that caught my eye and the eyes of some Hot Stove readers the past few months.

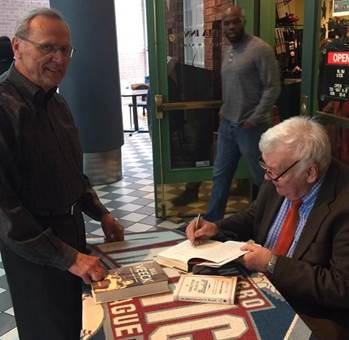

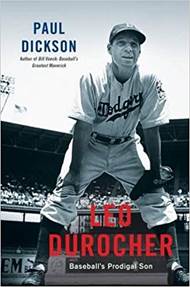

Leo “The Lip” Durocher: My memories of Leo Durocher mostly relate to his time managing the Giants of the 1950’s. I got a more complete picture from a recent Wall Street Journal review of a new Durocher biography by Paul Dickson. I was familiar with Dickson from his excellent 2012 book on Bill Veeck. By a nice coincidence, Dickson came to the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum on April 1 to give a talk on his book. Here he is signing my Durocher and Veeck books:

In his new book, Dickson recounts the Zelig-like presence of Durocher over a long arc of baseball history. Leo was a shortstop on two of the most famous World Series winners in history: the Murderers’ Row Yankees of 1928 and the Gashouse Gang Cardinals of 1934. Leo did not get along with Yankee great Babe Ruth. Leo humiliated Ruth and called him a dummy. Ruth claimed that Leo stole his watch, and bench jockeys for years would harass Leo by asking what time it was. Ruth called the good-field/no-hit Durocher the “All-American Out” and suggested that Leo become a switch hitter so he could bat .400, two hundred from each side of the plate. With the Cardinals, Leo played with the likes of Dizzy Dean and Frankie Frisch. Leo is often given credit for coining the “Gashouse Gang” name for the 1934 team. Leo had told a reporter that the Cardinals would not be allowed in the American League because “they say we’re just a lot of gashouse players.” The term gashouse referred to dirty and smelly factories in the bad end of industrial towns – matching what some saw as the shabby appearance and rough-and-tumble tactics of Cardinal players.

As early as 1939, Leo was a supporter of the integration of baseball, and so it was appropriate that he was the manager of the Dodgers in 1947 when Jackie Robinson joined the team. At spring training, Leo famously told players objecting to Robinson that they were free to go – Robinson was staying. Sadly for Leo, he was not around for the regular season because he was suspended for his association with gamblers. He moved to the Giants in 1948 and was at the helm when Bobby Thomson hit the “shot heard ‘round the world” to win the 1951 NL playoffs. He nurtured rookie Willie Mays in 1951 and was manager when the Giants won the World Series in 1954 (the one with “The Catch” by Willie). Leo later managed the Cubs and Astros. The baseball story of Leo is clouded by many personal failings, and his attitude is reflected in the title to his autobiography, Nice Guys Finish Last. The WSJ headline for its review captures the duality of Durocher: “The Devil at Shortstop.”

The night before his book signing, Dickson spoke to the Monarchs Club, a booster club for the NLBM. Dickson told our group that he would be in a future WSJ edition to give his top-five list of baseball books. The “Best Five” is a weekly feature in the Saturday Journal – an author naming favorite books in a given category. I asked him to name his books – so you are getting this Hot Stove scoop on the WSJ. His top-five are The Science of Hitting (Ted Williams), Moneyball (Michael Lewis), Only the Ball was White (Robert Peterson on the Negro Leagues), Ball Four (Jim Bouton, the first locker room exposé) and Veeck — as in Wreck (Bill Veeck with Ed Linn). If the WSJ had asked me, the list would have been Veeck and Moneyball plus Wait Till Next Year (Doris Kearns Goodwin on the Dodgers of Brooklyn), The Soul of Baseball (Joe Posnanski on Buck O’Neil) and The Last Boy (Jane Leavy on Mickey Mantle). To hedge on my list, any of the compilations of Roger Angell’s essays from the New Yorker can keep me happy for hours. If any Hot Stove readers are so inclined, send me your list of favorites.

Babe Ruth and Lonnie Shelton: Not a typo. Although my last name is spelled with an “a” – a quirk of the Americanization of the family name by my Lithuanian grandfather – the family has always pronounced it like it was an “e”. The same way former NBA star Lonnie Shelton pronounces his name. I have always distinguished myself from the NBA Lonnie by noting that he was taller, faster, richer and not Lithuanian.

Lonnie Shelton

I saw an article in the Wall Street Journal last year about another Lonnie Shelton who is also shorter, slower and not as rich as the NBA Lonnie. But he did spend a fair amount of money on a cool car. The Ford Motor Company gave Babe Ruth a 1948 Lincoln Continental in appreciation for his devotion to baseball and little leaguers. Ruth traveled the country in the car to give speeches and hitting lessons to little leaguers. This was the car owned by the Babe when he died on August 16, 1948.

The Babe in his Lincoln

The car was housed in a museum for many years and was purchased in 2012 by Lonnie Shelton of Pampas, Texas. He says the car has its original paint job and interior. The tube radio still works. Note the vanity plates: THE BABE.

Lonnie Shelton and Babe Ruth’s Car

Thutmose III At Bat: Proving the old adage that great minds think alike, this piece from the WSJ was sent to me last month by two Hot Stove readers, Paul Vardeman and Stan Bushman. The game of baseball started prior to the Civil War, but other bat and ball sports preceded that, cricket in England being a prime example. But who would have thought there was a predecessor thousands of years ago?

In a sacred wall painting in Queen Hatshepsut’s temple in Luxor, her stepson Thutmose III (1479-1425 B.C.) is shown ready to bat a ball at two priests. The inscription above him reads “striking the ball for [the goddess] Hathor,” and the one above the priests : “It is the priest who catches it for him.” Batting the ball was part of a fertility ritual with the ball representing the head of Osiris, god of the underworld.

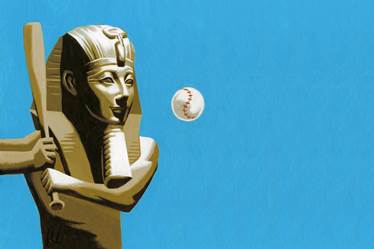

A precursor of baseball? Maybe a stretch, but I like the image used by the Journal to make the point:

Baseball, the Novel: Charley Helzberg sent me a WSJ guest article by Scott Simon, a voice many of you will recognize from NPR’s Weekend Edition. In his WSJ piece, Simon likens a baseball game to great literature and gives his opinion of why there are so many books about baseball. “One of the reasons there is so much good writing about the slowest of major American sports is that a baseball game can transport us like a fine novel.”

He proceeds with several literary paragraphs about a Cubs game last summer at Wrigley. Seattle had taken an early 6-0 lead. Simon talks about how pitch-by-pitch, scene-by-scene, the Cubs chip away at the lead. He shows how a lot of the drama takes place between plays (“The pauses in a novel can tell as much as the action.”). In the bottom of the 12th, with Jason Heyward on third with the potential winning run, pitcher Jon Lester is brought in to pinch hit. Lester lays down a bunt. The pitcher comes off the mound and swats the ball with his glove to quickly get it to the catcher. “As Heyward barreled down the third-base line, the catcher twisted home with a Bolshoi-worthy move. Too late. Heyward managed to sneak his left hand under Zunino’s tag while sailing by on his chin.”

The piece ends with this: “Baseball can be slow. So can parts of a fine novel. A typical game takes three hours – about the reading time of a short novel – and can be packed with irony and astonishment. A finger taps out the winning run at the last second through a cloud of dust. The game can remind you of the importance of precision, in every word and every pitch.”

Simon has been a Cubs fan since childhood and celebrated their first World Series in his lifetime by writing a book that was released this month – My Cubs: A Love Story. KCUR’s Steve Kraske discussed the book with Simon in a good interview earlier this month (click here, 26:42).

A Little Basketball – The Final Four: Jason Gay is a Wall Street Journal sportswriter who expertly combines wit and expertise in his writing. I did not think much of this year’s NCAA championship game, but Gay’s postgame article spoke to me. This year, Gay chose to sit in the upper deck to capture the experience of watching basketball from the back of a football stadium. I had similar experiences when I won lottery tickets for the Final Four at the New Orleans Kingdome (1987), Seattle Kingdome (1989) and the Minneapolis Metrodome (1992). I have no good excuse for doing this more than once. It is a horrible way to watch a game. But Gay makes it funny from his vantage point in the next to last row:

“To get there, I had to take escalators, and stairs upon stairs. I had to spend a week at basecamp on the 100 level in order to acclimate to the altitude…I brought binoculars …the kind you use to see giraffes…Also, because of fuddy-duddy NCAA rules, you couldn’t get a beer, which felt like a crime against humanity…It’s not just that the basketball game looked like a flea circus – the ambiance was weird, too…There were times when it felt as if we were watching the game in a totally separate stadium from Jim Nantz and the fancy people in the fancy seats down below…”

Gay talks about the theory that a basketball fan’s enjoyment is inversely proportional to the size of the gym. This also spoke to me. Although I have attended some fine college and pro games, including the 1988 KU-Oklahoma NCAA final, the most exciting game I ever saw was a loss by my Van Horn high school team to Lincoln in the city championship in 1959. Lincoln scored two baskets in the last 30 seconds to wipe out a 3-point Van Horn lead. The gym held about a thousand screaming fans. As Gay notes, “Is there anything better than a small, sweaty gym with everyone stomping on the wooden bleachers?”. No, there is not.

Music Note – Sylvia Moy: As often happens, a New York Times obituary introduced me to a name I did not know, but whose work I certainly knew. When Motown was considering dropping Stevie Wonder after his voice changed (his first hit had been at age 13), Sylvia Moy asked for the assignment. Loy was a singer/songwriter and the first female producer at Motown. Stevie and Sylvia made history together, and one of my favorite stories is how she changed Stevie’s draft lyrics from “Oh my Marsha” to “My Cherie Amour.” Good idea. NPR covers it well (click here, 2:22).