This year marks the 100th anniversary of the first Negro Leagues World Series played in 1924 between the Kansas City Monarchs and the Hilldale Club of Darby, Pennsylvania.

In 1920, the Monarchs and seven other teams had formed the first successful Negro League at a meeting at the Paseo YMCA in Kansas City. It was called the Negro National League (NNL) and operated mostly in midwestern cities.

In 1923, Hilldale and other east-coast teams formed the Eastern Colored League (ECL). The new league raided some players from the NNL, precipitating a two-year war between the leagues. The leagues made peace at the end of the 1924 season and sealed the deal with the league champions meeting in the first “Colored World Series.”

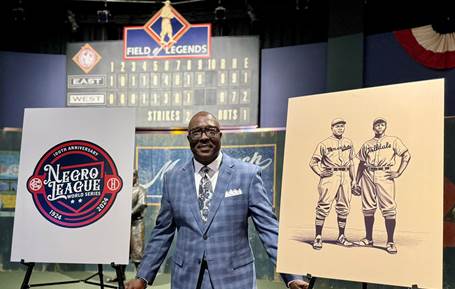

President Bob Kendrick of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum announced the museum will be celebrating the centennial with a series of city-wide events. Last month, Bob unveiled the logo commemorating the anniversary.

The Monarchs won that inaugural series, and Bob points out this was the first championship for a professional team in Kansas City. From Mayor Quinton Lucas: “It is important that we celebrate our champions…Think about the joy you had when the Super Bowl was won. Think about the joy you had when the Royals won the World Series in ’15 and in ’85. And think back to that being a thing in the community. Think about the euphoria that people in Kansas City in 1924 had the opportunity to experience. And no, it didn’t erase the challenges. It didn’t erase any of the issues that people faced, but it gave people some joy. It gave people something to love. It gave people something to believe.”

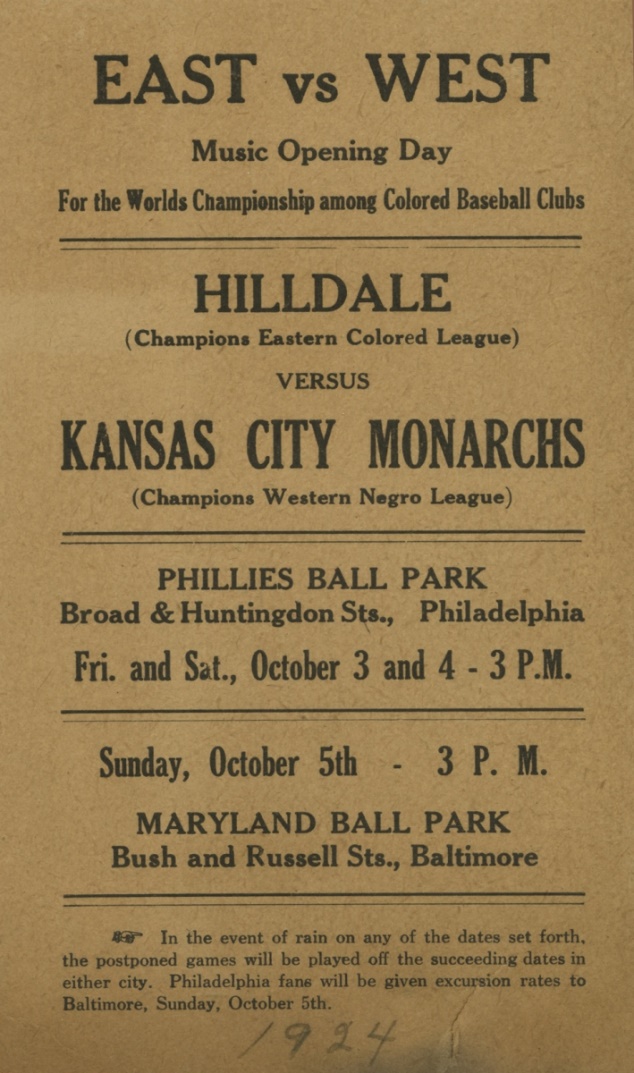

First Negro Leagues World Series – The Games: In the early years, the championship was called the “Colored World Series,” but was later referred to as the “Negro World Series” or the “Negro League(s) World Series.”

The 1924 series was a best-of-nine format. The first three games were “home” games for Hilldale, but not played in their regular home field in Dunbar. To accommodate larger crowds, the first two games were played in the Phillies’ park in Philadelphia (then known as the Baker Bowl). The third game was at Maryland Ball Park in Baltimore because Philadelphia did not allow baseball on Sundays.

The Monarchs roster included two future Hall of Famers: Bullet Rogan and Jose Mendez. Mendez was also the Monarchs manager. Hilldale had three future Hall of Famers: Judy Johnson, Biz Mackey and Louis Santop.

Games 1 and 2 (Philadelphia, below photo). Bullet Rogan pitched a 6-2 opening victory for the Monarchs, but Hilldale evened the series the next day with a blowout 11-0 win.

Game 3 (Sunday in Baltimore). The Monarchs took 1-run leads in the 9th and 12th, but Hilldale came back each time to even the score. The game was tied 6-6 in the 13th when it was called on account of darkness.

Game 4. The teams stayed in Baltimore to play the next day to make up for the tie game. With the score tied 3-3 in the 9th, Hilldale took advantage of two walks and two errors for a 4-3 victory.

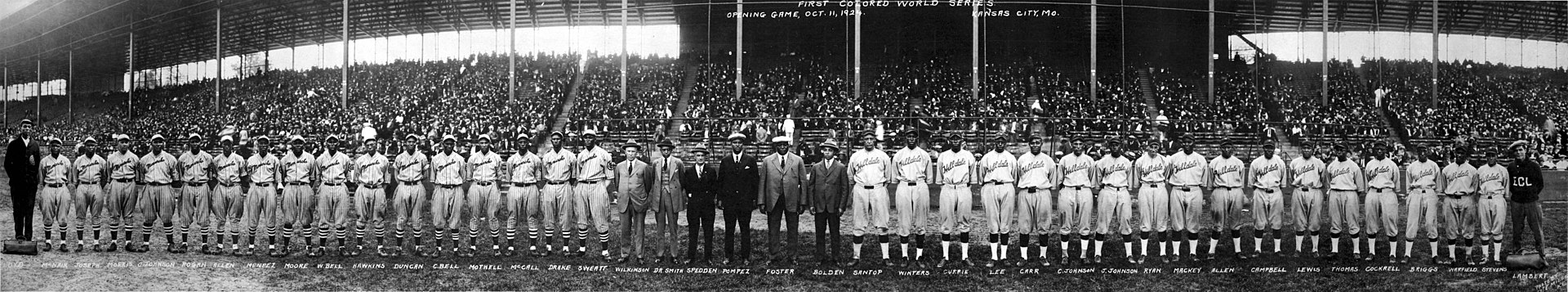

The series then moved to Kansas City for three games at Muehlebach Field. This panoramic photo from Game 5 is a classic. If you enlarge, you can read the names of the players and owners at the bottom. Two Hall of Fame owners are in civilian clothes in the center – the Monarchs J. L. Wilkinson (the only white owner in the NNL) and Rube Foster (owner of the Chicago American Giants and president of the NNL).

Game 5. Judy Johnson broke up a pitchers’ duel with a 3-run inside-the-park home run to carry Hilldale to victory. [Judy Johnson Trivia: He is the shortstop on the Field of Legends at the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum.]

Games 6 and 7. With Hilldale leading the series 3-1, the Monarchs rallied for two one-run victories in Games 6 and 7 to tie the series at 3-3.

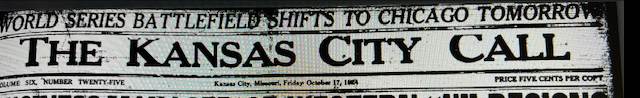

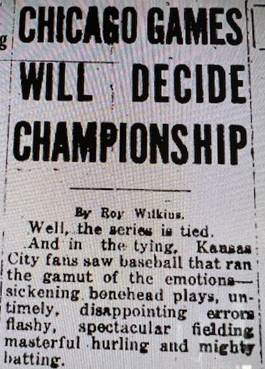

The next three games were played at Schorling Park in Chicago. On the front page of the Kansas City Call…

The column was written by Roy Wilkins, then the city editor of the Call. Wilkins of course went on to become a major leader of the Civil Rights Movement, including many years as the head of the NAACP.

Game 8 and 9. The teams split the next two games to tie the series at 4-4 (and one tie).

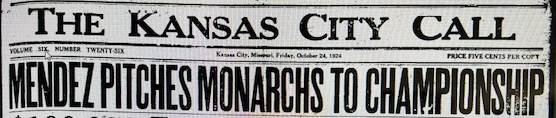

Game 10 (October 20, 1924). Monarchs’ player-manager Jose Mendez pitched a shutout for a 5-0 victory. The Monarchs were world champions!

I agree with Bob Kendrick. This is worth a season-long celebration. Please get by the museum for a visit in this centennial year.

The Monarchs of 2024: Also celebrating the centennial will be the Kansas City Monarchs of the independent American Association. The team began play as the T-Bones in 2003, and after a break for Covid, came back in 2021 rebranded as the Monarchs, winning league championships in 2021 and 2023.

The Monarchs play at Legends Field in Kansas City, Kansas, and the 2024 home season will kick off on May 16. The team is known for its fun promotions, affordable tickets and free parking. Website here.

JE Dunn – 1924 to 2024: In that Monarchs championship season of 1924, John Ernest Dunn founded JE Dunn Construction Company. Today, the company is the eighth-largest domestic general contractor in the United States with offices in 26 locations.

The company has some baseball roots. J. E. Dunn was a semi-pro pitcher for Portland in the Pacific Coast League. His sons Ernie and Bill Dunn also played ball, with Bill Dunn pitching in the American Legion league against Yogi Berra and Joe Garagiola. The following generations have followed as players and fans, so it was an easy decision for the Dunn family and the company to join John Sherman as co-owners in purchasing the Royals in 2019.

In its own centennial year, JE Dunn is partnering with the Royals to “Celebrate the Run” in honor of the Monarchs 1924 championship. Every run scored by the Royals during the 2024 season means a $100 donation to the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum. So, this gives Royals fans an extra reason to root for lots of runs. As of Monday’s game, the Royals have scored 164 runs. $16,400. And counting. Keep ‘em coming!

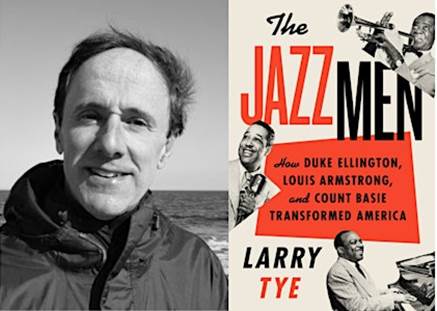

Larry Tye – Author on Baseball and Jazz: In 2004, best-selling author Larry Tye published Rising from the Rails: Pullman Porters and the Making of the Black Middle Class. In a recent interview, Tye spoke of his work on that book and how it inspired him to write two future books:

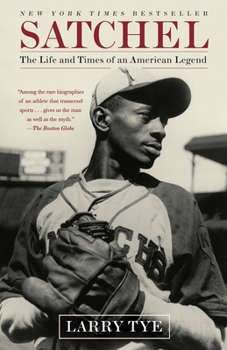

“I wrote a book almost 20 years ago about the Pullman porters, who formed the first Black trade union. When I was talking to the porters, they made me promise to write two books: one about their favorite sports figure, Satchel Paige, and the other about their favorite passengers, Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, and Count Basie. When these musicians traveled below the Mason-Dixon line, they’d hire Pullman cars to have a safe place to eat and sleep after their performances. After they returned to the Pullman cars, they would often hold late night private jam sessions for the porters.”

Tye covered the first part of the promise with his 2009 book Satchel: The Life and Times of an American Legend. It is a terrific book – without doubt the definitive biography of Satchel Paige.

And released yesterday, part two of the promise. The Jazz Men: How Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, and Count Basie Transformed America.

Larry Tye on his Jazz Men: “They were all born into the nascent jazz world at about the same time, and each encountered many of the difficulties faced by Black musicians. Their stories also trace the development of different styles of jazz in the cities where they got their start: Kansas City [Basie], New York City [Ellington], and New Orleans and Chicago [Armstrong]. Each took a different approach to jazz: Armstrong could hit his high C’s; Ellington could tell stories about Black America in his symphonic pieces; Basie couldn’t resist tapping his feet, and he got his audiences’ tapping theirs as well.”

On May 16, Larry Tye will be in Kansas City to promote his book. In a joint presentation by Rainy Day Books and the American Jazz Museum, Tye will be in conversation with Chuck Haddix (host of Fish Fry) at 6:00 PM at the Reno Club in the Ambassador Hotel. Ticket info here.

The selection of the Reno Club for this book event was an inspired choice. The original club at 12th and Cherry was where Count Basie’s career blossomed and became nationally known through radio broadcasts from the club. Today’s Reno Club is just five blocks from the original and is known as Lonnie’s Reno Club to give deserved recognition to the multi-talented star performer Lonnie McFadden.

Rita and I have been to the club with Irv and Sharyn Blond, and we all loved the evening. It’s like being transported back to a 1930s supper club. Full report in Hot Stove #186. Below, Lonnie and Lonnie.

Lonnie’s Jukebox – Jazz and Baseball: When Ken Burns speaks about his documentaries on baseball and jazz, he often quotes essayist Gerald Early, “When they study our civilization two thousand years from now, there will be only three things that Americans will be known for: the Constitution, baseball and jazz music. They’re the three most beautiful things Americans have ever created.”

From Smithsonian curator John Hasse, “Baseball and jazz both use swing as a noun and a verb, and in both fields, swing involves time and timing.”

Martin Luther King Jr. praised jazz and baseball as unifying forces in advancing the Civil Rights Movement. White audiences exposed to Black musicians and baseball players were more likely to be receptive to what King was doing.

A ball player with a great appreciation for jazz was Buck O’Neil who said, “Baseball is better than sex. It is better than music, although I do believe jazz comes in a close second. It does fill you up.”

Now, with a little help from Buck, some baseball trivia and recordings for each of Larry Tye’s Jazz Men.

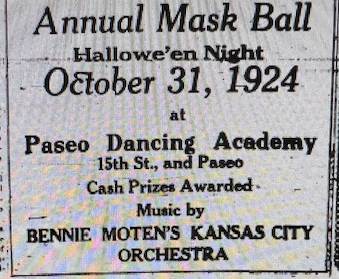

Count Basie: In the same Kansas City Call issue that headlined the Monarchs as champions in 1924, there was this display ad…

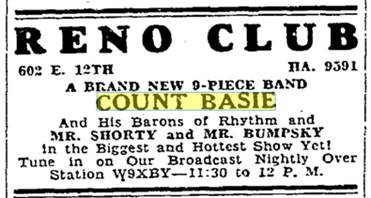

Bennie Moten’s orchestra was popular in both Black and white venues in segregated Kansas City. In the late 1920s, piano player Count Basie joined Moten. After Moten died in 1935, Basie put together his own band and settled into a house band operation at the Reno Club at 12th and Cherry. When I searched the archives of the Kansas City Call, I found little mention of the Reno Club, initially forgetting that the Reno was a “white” club. Since the clientele was white, ads for the club ran in the Kansas City Star.

Note the last line of the ad. Basie’s shows were on radio station W9WBY, which covered a large part of the country in the nighttime skies. Because of this, Basie’s brand of Kansas City swing caught the attention of record labels, and his career took off. He went from playing a club in KC to being an international star.

The players of jazz and baseball often crossed paths as they toured the country. They ate at the same restaurants and stayed in the same hotels, mostly those listed in the Green Book as welcoming African Americans. It was common for the musicians to attend baseball games in the afternoon and the baseball players to go to the clubs at night. Buck O’Neil spoke of this difference in working hours by describing a morning conversation when he saw Count Basie in a hotel lobby: “’Good morning, Count, I’d say. ‘Good evening, Buck,’ Mr. Basie would say.”

Buck again on Basie: “Basie was a Yankee fan, and I’m a Dodger fan. And we would bet every year on the Yankees and Dodgers. You know he beat me most of the time, but we had a lot of fun.”

This is a long Hot Stove (but aren’t they all). Take a break and listen to some Count Basie.

“One O’Clock Jump”. This arrangement was being played by Basie at the Reno Club, and the band called it “Blue Balls.” When it was played on the radio feed from the Reno, the announcer thought he should not say that title. So, they looked at the clock, about 1:00 AM, and “One O’Clock Jump” was born. It became Basie’s theme song and was recorded in his first session with Decca in 1937.

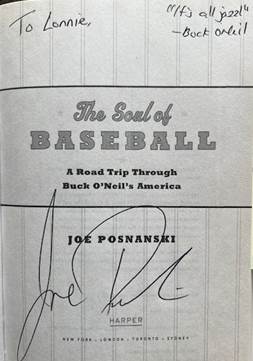

“Jumpin’ at the Woodside”. In Joe Posnanski’s beautiful book about Buck O’Neil (The Soul of Baseball), Buck tells the story of weekend baseball in Kansas City, including seeing Count Basie playing “Jumpin’ at the Woodside” on Saturday nights, then coming down for Sunday breakfast at the Street Hotel where celebrities like Joe Louis and Billie Holiday would be in the dining room. A version of the song is also a cut on the album Satch and Josh (as in Hall of Famers Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson).

“Did You See Jackie Robinson Hit That Ball”. When Basie’s version was released in 1949, Jackie Robinson was in his third season with the Dodgers and Buck O’Neil was the player-manager for the Monarchs.

Duke Ellington: Buck O’Neil: “Duke was sophisticated and clean. Clean music. Like with Lionel [Hampton], you wanted to dance, Duke, you wanted to listen.”

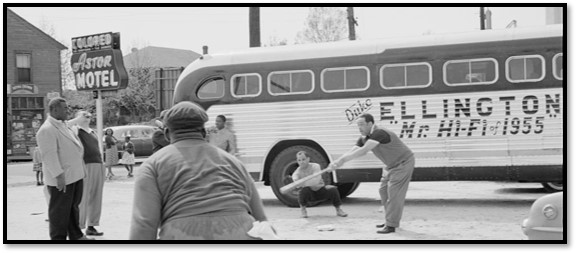

During the swing era, it was common for the big bands to form baseball teams (e.g., Benny Goodman, Count Basie, Tommy Dorsey and Duke Ellington). The size of the bands provided enough players to field a team. Here’s Duke taking some batting practice while out on tour. Note the “COLORED” sign atop the motel sign. Jim Crow still active in 1955.

Also, there is a cool vintage clip of Ellington pitching and batting (click here).

Time for another break, this time with Duke.

“It Don’t Mean a Thing (If It Ain’t Got That Swing)”

Louis Armstrong: Buck O’Neil: “That was music you could listen to, and you could laugh with Louie because Louie had kind of a laughing horn. When he blew that horn, you’d laugh about the different notes he’s play. The thing about it is, that handkerchief he had to cover up so nobody was coppin’ those things. Quite a fella. Baseball nut too; he liked baseball.”

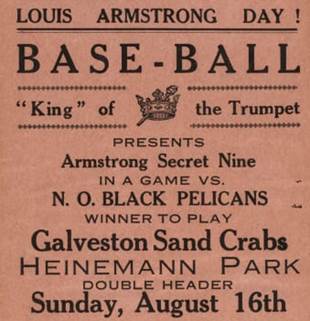

In New Orleans in 1931, Armstrong outfitted a team known as the “Armstrong Secret 9.” Below, Armstrong (standing with the bat) with his team.

He sometimes threw out the first pitch at the games.

Lots of well-known songs by Satchmo. A sample.

“In My Solitude”. Armstrong’s 1935 version of a Duke Ellington composition.

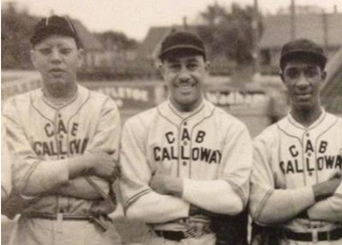

Cab Calloway: Although not one of the named Jazz Men in Larry Tye’s book, I need to include Cab Calloway. He owned his own baseball team and played infield (center below).

And his “Minnie the Moocher” is often heard at sports stadiums today with the fans doing the call and response…

Hi-de-hi-de-hi-de-hi (hi-de-hi-de-hi-de-hi)

Ho-ho-ho-ho-ho (ho-ho-ho-ho-ho)

Hee-de-hee-de-hee-de-hee (hee-de-hee-de-hee-de-hee)

Hey-ey-ey (hey-ey-ey)

“Minnie the Moocher” by Cab Calloway at a Royals game in 1990. It’s also great fun to see him sing it live (click here).

![The Soul of Baseball: A Road Trip Through Buck O'Neil's America [Book]](https://lonniesjukebox.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/the-soul-of-baseball-a-road-trip-through-buck-on.jpeg)

I’ll end this piece with some words from Buck O’Neil. Both anecdotes are from The Soul of Baseball.

Buck told a story of being on Vine Street walking around with Duke Ellington. They walked into a club where a chubby Kansas City kid is blowing on a saxophone. “He played it fast and wild and all over the place…You just don’t hear too many things that are just different…Charlie Parker. Oh man, Charlie Parker…People feel sorry for me. Man, I heard Charlie Parker.”

While Posnanski traveled around the country with Buck, music followed them. Jazz stories and listening of course, but also whatever might come up on the radio or from a street musician. Johnny Cash, the Beatles, 50 Cent, gospel, etc. One day Buck was signing autographs and was tapping his toe to Billy Joel’s “My Life,” which was playing on a speaker nearby.

Buck: “I like this.”

Joe: “Billy Joel isn’t exactly jazz.”

Buck: “It’s all jazz.”

Buck knew how to uncover joy. Make people feel more positive about life. The relentless optimist. Posnanski obviously loved the attitude. When signing copies of his book, Joe quotes Buck…