Over the past couple of months, I have encountered several Kansas City stories from a century ago. Baseball. Barbecue. Prohibition. Jazz. Crime. Pendergast. Harry Truman. I’ll start with the baseball.

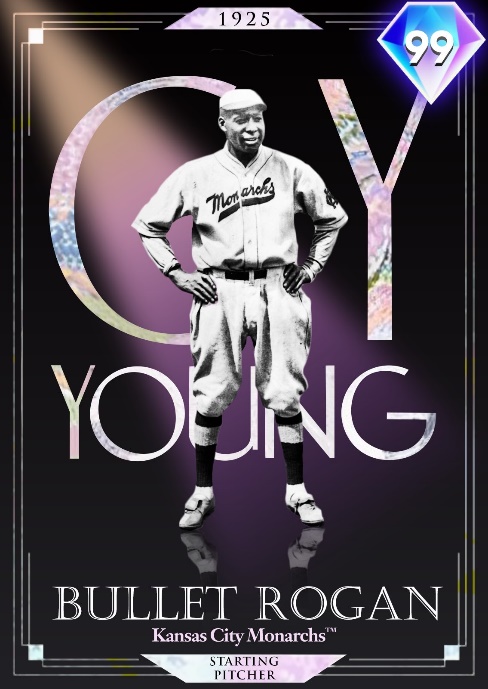

Wilber “Bullet” Joe Rogan: In February of 1920, the first Negro League was established at a meeting in Kansas City at the YMCA at 19th and Paseo. One of the original teams was the Kansas City Monarchs, and for the next ten years, one of the biggest stars on the team was Wilber “Bullet” Joe Rogan who attended Sumner High School in Kansas City, Kansas. Rogan was a two-way superstar, hitting and pitching, maybe the most comparable precursor to Shohei Ohtani (see Hot Stove #167).

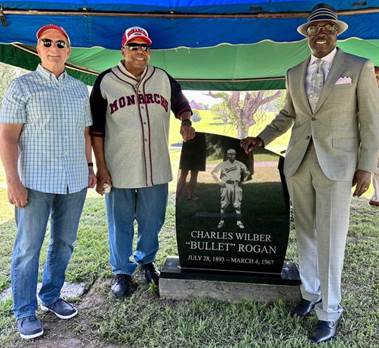

Rogan is in the National Baseball Hall of Fame. But you would not have known that from his non-descript headstone at his Kansas City gravesite. This caught the attention of local attorney Kevin Kenney who started a GoFundMe campaign to raise money for a proper remembrance. The campaign was successful, and on May 17, the monument was unveiled. Below, at Blue Ridge Lawn Memorial Gardens, Kevin Kenney, Carl Rogan (grandson of Bullet) and President Bob Kendrick of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum. Kudos to Kevin Kenney!

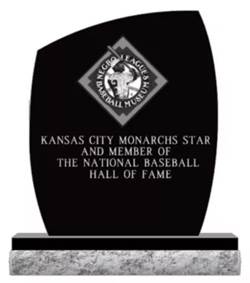

The reverse side of the monument:

Bullet Rogan is one of the featured pitchers in a new NLBM exhibit that chronicles the legacy of Black and Latino pitchers. “Black Aces” will be at the museum until September 30 (click here for Bob Kendrick’s promo of the exhibit).

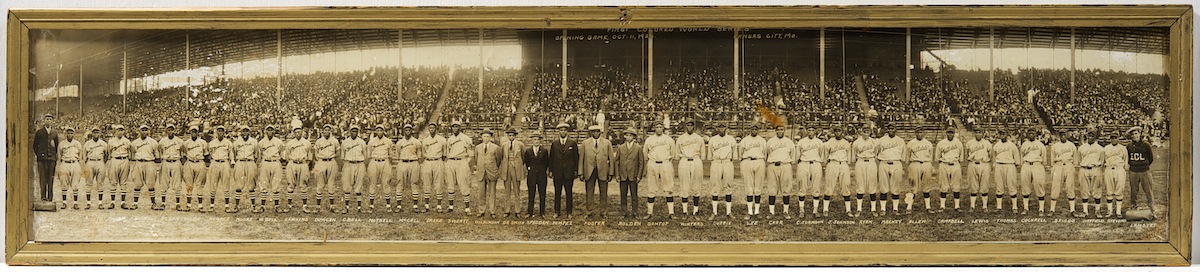

The Monarchs in the Roaring Twenties: During the 1920s, the Monarchs won six pennants. In 1923, the team moved from Association Park to the new Muehlebach Field at 22nd and Brooklyn. In 1924, the Monarchs won the first Negro League World Series (photo below).

The players were like royalty in the Black community where entertainment was centered in the blocks around 18th and Vine. And 18th and Vine was hopping. Booze (and other vices) were in abundance as the city of Pendergast ignored Prohibition. The music coming out of the clubs and dance halls would evolve into Kansas City jazz.

Also, another signature Kansas City tradition was in the making…

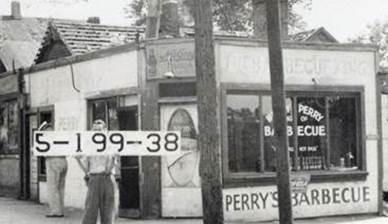

Kansas City Barbecue: Henry Perry started selling barbecue from a stand in Kansas City’s garment district in the 1910s. He moved to the popular 18th and Vine area, and business boomed in the Roaring Twenties. The self-proclaimed “King of Barbecue” was so popular that he served an integrated clientele in uber-segregated Kansas City.

A century has gone by, and Henry Perry’s legacy is still on display. One of his cooks, Arthur Pinkard, helped George Gates found Gates Bar-B-Q. Perry’s employee Charlie Bryant inherited part of Perry’s business, later selling it to his brother Arthur Bryant. Coincidentally, I ate some barbecue this month at both Gates and Arthur Bryant’s.

The Bryant’s lunch was organized by Leland Shurin who put together a group of five to journey down to 18th and Brooklyn. This brings back fun memories for me, dating back to 1968. Hollis Hanover and I were just out of law school and working at the Popham firm. One of the rights of passage was for new associates to be lured by junior partners (Bob Russell and Mike Maloney) to eat barbecue and drink beer to excess at Bryant’s. I now go with smaller portions and pass up noon-hour beer.

Last week, Mark Bryant and I had lunch at the Gates on Emanuel Cleaver Boulevard where 90-year-old Ollie Gates is there most days, holding court and greeting friends and customers.

Mark and I reminisced with Ollie, and he retold the story of how he labeled Steve Glorioso (RIP) and me as the “Katzenjammer Kids” during the 1979 mayor’s campaign. Steve and I were among those working to elect Ollie’s friend Bruce Watkins as the first Black mayor of Kansas City. I’m not sure I understood the Katzenjammer reference, but it was a memorable campaign. Bruce did not win, but his strong effort paved the way for Alan Wheat’s election to Congress three years later. And then for future mayors Emanuel Cleaver, Sly James and Quinton Lucas.

In 1999, a stretch of Brush Creek Boulevard was renamed Emanual Cleaver II Boulevard. I think it’s cool that two of the businesses on that stretch acquired Cleaver Boulevard addresses – Gates Bar-B-Q (1325) and Watkins Funeral Home (4000).

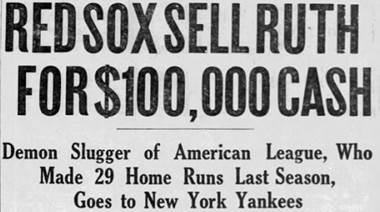

Babe Ruth and Prohibition: Over in the American League, the MVP of Prohibition-deniers was Babe Ruth. In December of 1919, Ruth had been sold by the Red Sox to the Yankees, and as recounted by Jane Leavy in her wonderful 2018 book, The Big Fella:

“He was a one-man antidote to the grimness of Prohibition. He had arrived in New York ten days before the Eighteenth Amendment went into effect, fleeing puritanical New England for the joie de vivre of Broadway. He was a beer man and drank lots of it. Later he had a tap installed in the sink of his Riverside apartment.”

In the 1920s, Ruth led the Yankees to six pennants (same as the Monarchs) and three World Series victories. Ruth also barnstormed after the season, and despite disapproval of Commissioner Kenesaw Landis, Ruth often played against Negro League teams (e.g., the Monarchs in KC in 1922).

In 1927, Ruth hit 60 homers for a record that held until 1961. Again from Jane Leavy:

“In a city of rule breakers – everyone who bent an elbow in 1927 was breaking the law of the land – he was the rule breaker in chief…he gave the public glimpses of a bad boy having the time of his life.”

Ruth’s antics extended to spring training where the bathtub in his hotel suite in St. Petersburg was filled every night with Prohibition liquor.

In the 1928 race for president, Ruth backed New York governor Al Smith over the Republican Herbert Hoover. It’s easy to see why. Smith opposed Prohibition and was an early supporter of Sunday baseball.

Hoover won, but Ruth got a good line out of it. In 1930, Ruth signed a Yankee contract for $80,000 ($1.4 million today). When asked if he deserved to be making more than President Hoover, Ruth replied, “Why not? I had a better year than he did.”

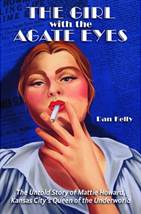

A Chain of Kansas City Trivia from a Century Ago: On November 11, 1921, Mattie Howard entered the Missouri State Penitentiary to begin serving her 12-year sentence for murder. The story of why she was there is told by Kansas City Star columnist Dan Kelly in a new book titled The Girl with the Agate Eyes: The Untold Story of Mattie Howard, Kansas City’s Queen of the Underworld.

A brief summary from the author: “Mattie Howard cracked safes and robbed banks. She was a drunk, a fugitive, and an adulteress. But did she murder Diamond Joe Morino?” Dan will give a presentation on his book at the Central Kansas City Library on August 6.

There was a lot of newspaper coverage of crime in those days (Star, Post and Journal), and Mattie was good copy. She combined fashion and sexual freedom, but was not just some gun moll – she was a cold-blooded gangster who the local papers called “the girl with the agate eyes.”

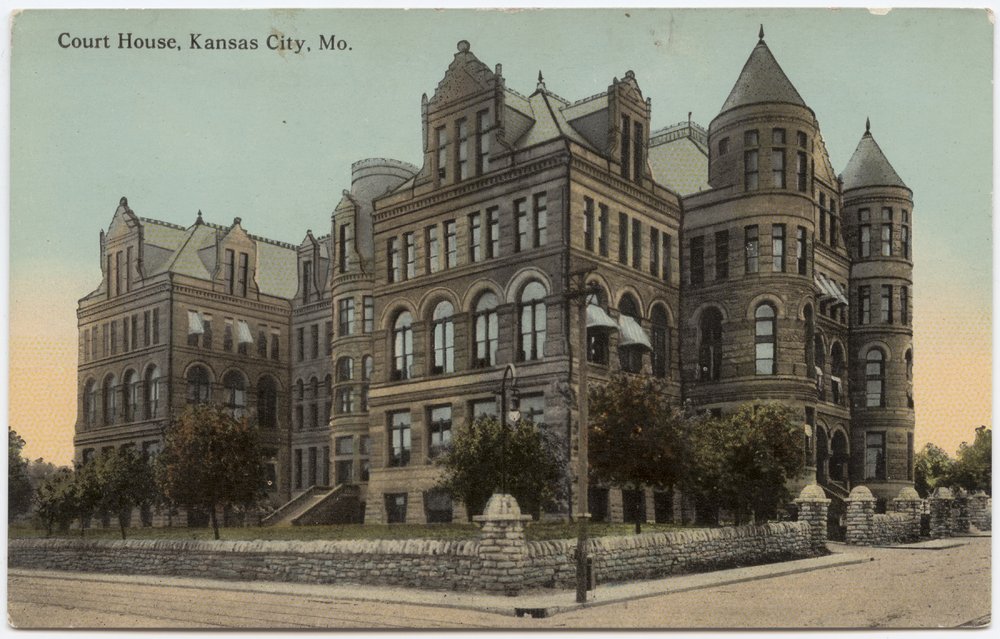

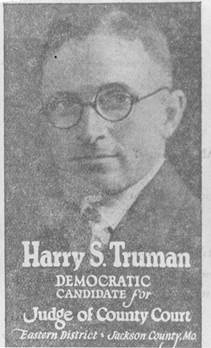

Mattie’s trial was in the courtroom of Judge Ralph Latshaw in the Jackson County Courthouse located at 5th and Oak. [Courthouse Trivia: This courthouse would be replaced in 1934 in a public building boom overseen by the presiding judge of the Jackson County Court – Harry Truman.]

The prosecutor’s office was aided by James P. Aylward, a special prosecutor hired by the victim’s estate. Mattie was represented by Jesse E. James (a/k/a Jessie James, Jr. and the son of the famous outlaw). Mattie was found guilty, served her prison term and, in a strange twist, became an evangelist.

Jesse E. James Trivia: James previously appeared in Hot Stove when Pat O’Neill wrote a guest piece on a Pendergast baseball team. James owned the cigar stand in the Jackson County Courthouse (the photo above) in the early 1900s and played on an amateur baseball team organized by Jim Pendergast. Partial lineup: Big Jim Pendergast (First Base), Boss Tom Pendergast (Third Base) and Jesse James (Center Field).

James was tried for train robbery in 1899, but was acquitted. He later got his law license and often represented criminal defendants. Apparently not well, because Mattie was only one of his many losses.

James P. Aylward Trivia: With the help of the Pendergast machine, Harry Truman was elected Eastern Judge of the Jackson County Court in 1922.

When Truman was elected, the chair of the Jackson County Democratic Committee was James P. Aylward who held that position from 1918 to 1936. Aylward was trusted by the Pendergast “goats” and the Shannon “rabbits” to broker their differences and make peace after hard fought elections. In 1934, Tom Pendergast asked Aylward to run for the U.S. Senate, but Aylward declined and handed off the candidacy to Harry Truman and managed his campaign.

In 1936, Aylward made one of the nominating speeches for Franklin Roosevelt at the Democratic National Convention. Below, Senator Truman, Tom Pendergast and Aylward at the convention.

Coon-Sanders Nighthawks: In Hot Stove #224, Lonnie’s Jukebox included some songs from the Coon-Sanders Nighthawks, a Kanas City-based swing band that gained national fame during the Roaring Twenties. This prompted two readers to add some good trivia.

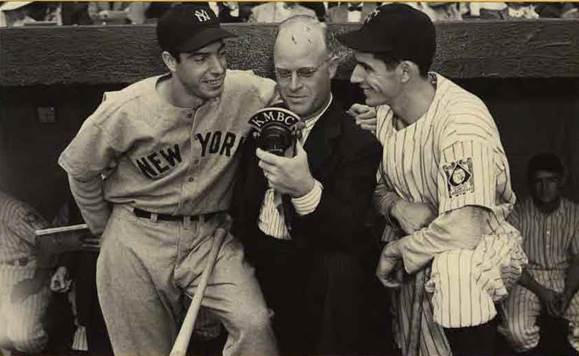

Bill Lochman Trivia: Bill Lochman, a friend since our days at Van Horn High School, is the son of Walt Lochman who became a household name in Kansas City as a sports broadcaster. But that’s not how Walt started in radio. Bill says that the story passed down through the family is that Walt’s first radio work was a singing job on a musical variety show. Walt had a good voice and that earned him some spots alongside the Coon-Sanders band on some of their national radio broadcasts.

Walt later used his good voice to follow his dream of becoming a sports broadcaster. In 1935, he talked KC Blues owner Johnny Kling into testing the broadcasting of games. It was a big success, and Walt would eventually broadcast over a thousand Blues games. Below, from my Hot Stove profile on Walt Lochman, at a 1939 Yankees-Blues exhibition game with Joe and Vince DiMaggio. This game also marked the final appearance of Lou Gehrig on the field.

In 2016, Bill and I listened to some recordings of his dad broadcasting Blues games. This was set up by Chuck Haddix who is the director of the Marr Sound Archives at the Miller Nichols Library at UMKC. Speaking of Chuck…

Chuck Haddix Trivia: Chuck Haddix (a/k/a Chuck Haddock of KCUR’s Fish Fry) told me about a baseball story attached to Joe Sanders, the piano playing leader of the Nighthawks.

In a 1989 Star Magazine article about the band, Joe Popper wrote that Joe Sanders billed himself as the “Ol’ Left Hander,” a reference “not to the throbbing base line he played on the piano, but to his self-proclaimed ability as a baseball pitcher.”

One of Joe’s claims to fame was striking out 27 men in an official league game, but with some vagueness about what league. He said he was offered a contract by the minor league Kansas City Blues, but decided to proceed with his musical career.

The story could well be true – Joe’s older brother Roy played two years in the majors and was a good friend of Casey Stengel (who attended Roy’s wedding per Hot Stove sources Suzanne Meyer and Debby Bird, Roy’s granddaughters). So this leads to…

Casey Stengel Trivia: Charles Dillon Stengel, nicknamed “Casey” for his hometown of Kansas City, had a 14-year career as a player in the major leagues (1912-1925). In 1917, he played for the Pirates, and one of his teammates was Roy Sanders.

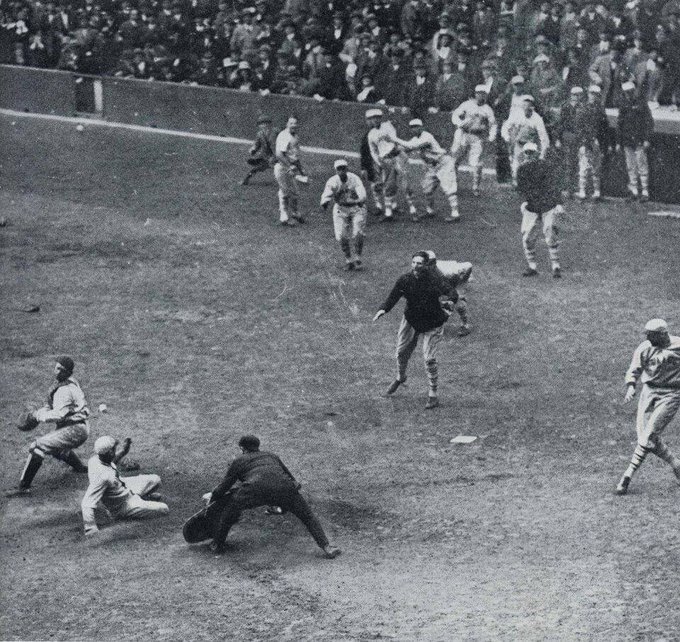

From 1921 to 1923, Casey played for John McGraw’s New York Giants, and in each of those years, the Giants played the Yankees in the World Series. The Giants won in 1921 and 1922. In 1923, the new Yankee Stadium was opened, and the Yankees were still looking to win their first World Series.

In Game 1, with the score tied 4-4 in the 9th inning, Casey hit an inside-the-park home run to give the Giants a 5-4 win (photo below). Casey was reprimanded by Commissioner Landis for thumbing his nose at the Yankee bench after the homer. [Inside-the-Park Trivia: There have been 10 inside-the-park home runs in the World Series, the most recent by Alcides Escobar of the Royals in 2015.]

After a loss to the Yankees in Game 2, the Giants came back to win Game 3 by a 1-0 score. The only run was a homer by Casey (this one over the fence). But that was it. With a strong performance from Babe Ruth, the Yankees won the next three games to take the Series.

Stengel/Rogan Trivia: In 1917, while on extended furlough in Kansas City, Bullet Rogan joined the barnstorming multi-racial All Nations team owned by J. L. Wilkinson. The story, possibly apocryphal, is that Wilkinson got a tip from Casey Stengel that Rogan would be a good prospect. Stengel and Rogan likely crossed paths while playing the semipro circuit in the Kansas City region.

When the first Negro League was formed in 1920, Wilkinson acquired the Monarchs franchise, and Rogan and several other All Nations players became Monarchs. Below, a retro baseball card imagining Rogan as the Negro Leagues Cy Young winner.

“The People Are Thirsty”: When Rita and I were recently in New York, we saw Some Like It Hot, a musical set in the time of Prohibition. The opening number is “What Are You Thirsty For” (listen here). Among other things, people were thirsty for booze.

This may sound familiar to Kansas Citians. It is said that when Tom Pendergast was asked how he justified ignoring Prohibition, he quipped “The people are thirsty.” I am reminded of this every time I travel down Main Street in the Crossroads and see this sign on the Tom’s Town Distilling building:

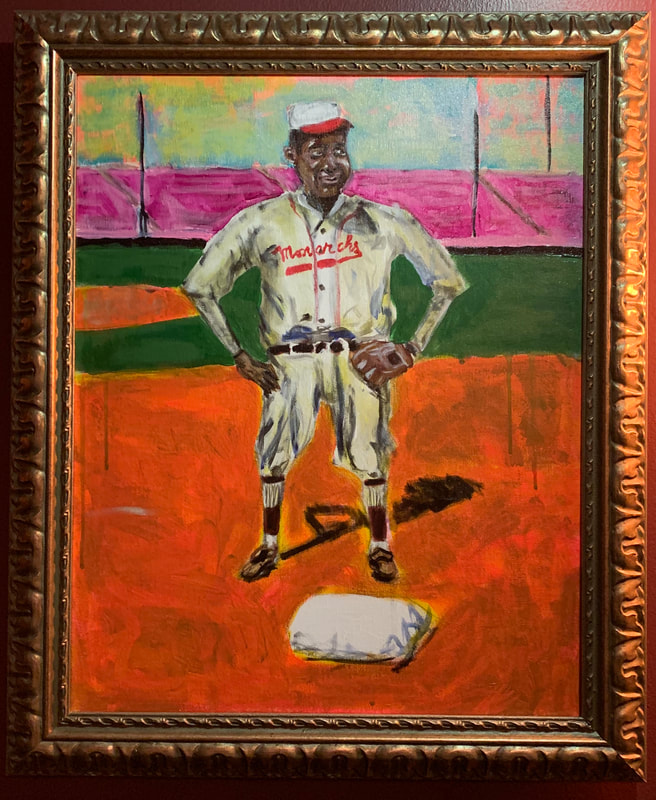

In the “Pendergast Lounge,” a speakeasy-style room at Tom’s Town, there is a gallery of portraits by local artist Hubbard Savage. These include Carrie Nation (!), F. Scott Fitzgerald (Jazz Age novelist/Great Gatsby), saxophone genius Charlie Parker, and the man who started this Hot Stove post, Monarchs Hall of Famer Bullet Rogan.

Lonnie’s Jukebox – Roaring Twenties Edition: The new technology of radio and the live music embraced by speakeasies and dance halls led to an explosion of music in the 1920s.

Kansas City had some nationally known performers, including the Coon-Sanders Nighthawks, playing for white audiences, and over at 18th and Vine, Benny Moten who would take on piano player Count Basie in 1929. Another major band at 18th and Vine was led by George E. Lee…

“St. James Infirmary” by the George E. Lee Singing Novelty Orchestra (1929). In 1923, Lee’s band (photo below) became the first African American band from Kansas City to record. His sister Julia Lee, playing on the piano on “St. James Infirmary,” became a national recording star.

“Kansas City Shuffle” by Bennie Moten’s Kansas City Orchestra (1926). Moten’s band nurtured many musicians who became stars in the Jazz Age and beyond.

“Darktown Strutter’s Ball” by the Coon-Sanders Nighthawks (1929). This song has been covered by most big bands and by artists ranging from Bo Diddley to Dean Martin to Fats Domino (Fats’ version here).

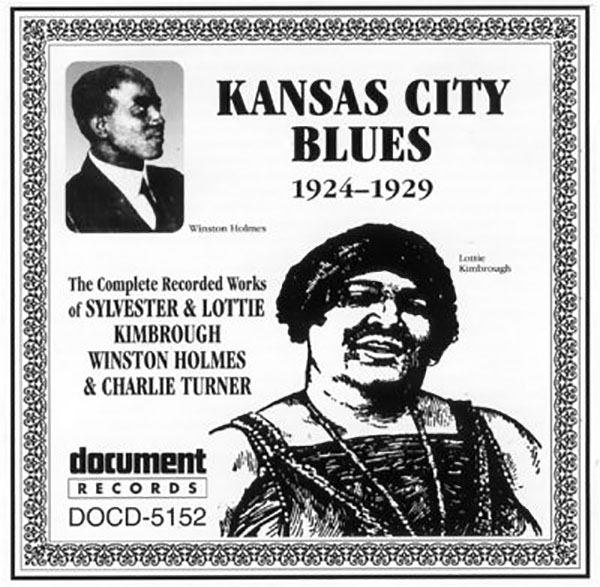

“Going Away Blues” by Lottie Beaman, a/k/a Lottie Kimbrough (1928). This selection came on a tip from Steve Paul who shared an essay he wrote about Lottie who had “a big, woeful, bluesy sound that put some listeners in mind of Gertrude ‘Ma’ Rainey.” Lottie sang in Kansas City speakeasies and made some recordings in the 1920s, but then disappeared from public view.

“Who’s Sorry Now” by Isham Jones and His Orchestra (1923). Most of us will instead remember the 1958 Connie Francis version (click here).

“St. Louis Blues” by Bessie Smith (1925). This is the definitive version of W. C. Handy’s song that has been recorded over a thousand times. Not to be confused with the current feelings of St. Louis Cardinals fans.

“Corrine Corrina” by Bo Carter (1929). This country sounding version is nothing like the 1956 rocker by blues-shouter Big Joe Turner who got his start at 18th and Vine (Joe’s version here).

“Stardust” by Hoagy Carmichael (1927). I liked the 1958 version by Billy Ward and His Dominos (click here).

“Charleston” by Paul Whiteman and His Orchestra (1925). The obvious finale for the Roaring Twenties.

There are many more of course. Rudy Vallee, Paul Robeson, Al Jolson, Fats Waller, Louis Armstrong, Eddie Cantor, Duke Ellington, etc., but I’m tired after dancing the Charleston.

I’ll sign off with Ted Lasso and his mashup of Kansas City Barbecue. Henry Perry would be proud.