Without knowing it at the time, this Hot Stove post began percolating in my mind at Van Horn High School in about 1957. I had turned 16 and now had the pleasure of listening to rock ‘n’ roll while driving. Jim Graham, a pal since grade school, and Bill Lochman, a new friend in high school, invited me and my 1954 Ford to join their hot rod club, the Draggin’ Diplomats. My parents were not that keen on the hot rod thing, but they passed along some info on my new friend Lochman – they said that Bill’s dad Walt was well known to them as the early radio voice of the Kansas City Blues. It turned out that almost everyone from my parents’ generation was familiar with Walt Lochman who broadcast the Blues games from 1935 to 1942. Bill of course confirmed this to me, but I never met his dad who had died in 1954. Over the last year, a couple of reminders of Walt Lochman put me on the trail of a special KC baseball story.

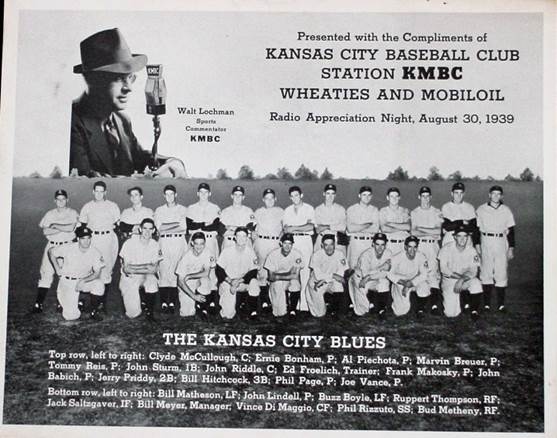

Chappell’s and Walt Lochman: I gave up hot rods when I went off to college, but after law school, Bill and Jim lured me back into their new phase of social life, the Young Democrats. The “Young” part of that is long gone, but after more than a half century of friendship, we have a monthly lunch that is heavy on nostalgia. Last year, Jim suggested we schedule one of our lunches at Chappell’s, a North Kansas City restaurant that has sports memorabilia covering the walls, ceiling and every nook and cranny. Graham was on a mission: he had once seen a Walt Lochman photo among the thousands of artifacts, and sure enough, there it was on a wall. In a later visit to Chappell’s, I met owner Jim Chappell who gave me a tour and pointed out a second Lochman photo. The two items were the 1939 and 1940 team photos produced by the radio broadcast sponsors. Here is the 1939 version (note Phil Rizzuto and Vince DiMaggio on the first row):

Roger Angell and Walt Lochman: The other reminder came from my reading of Late Innings, one of the anthologies of baseball essays by Roger Angell from the New Yorker. In a piece dated October 1980, Angell tells of being in Kansas City to cover the World Series between the Royals and Phillies. He picks up background information from some locals:

“Much of this midlands cultural history was given to me during a memorable supper of ribs and baseball (and frosty pitchers of draft beer) in the side room of Arthur Bryant’s Restaurant, a Tour d’ Argent of barbecue, just after Game Four. My friendly companions were Jim and Dana, both faculty members of the University of Kansas; a free-lance writer named Bill; and Jim’s seventeen-year old son, Mike. All these humanists had watched and thought about Kansas City ball throughout their lives, and as they talked and laughed and argued their voices seemed to flow and part and intermingle into a single river, a murmurous Missouri of baseball memories.”

Angell over several pages recounts the back of forth of this with names and events familiar to Kansas City fans: Blues, A’s, Otis, Hurdle, Mayberry, McRae, Rojas, Busby, Whitey, Yankee connections, Charlie Finley, Monarchs, Portocarrero, Zernial, Buddy Blattner, and ….this:

“Do you remember Walt Lochman during the Blues’ road games over the radio—those re-creations, with the funny fake game sounds and the telegraph ticker going in the background?”

I was so pleased to see this nugget – obscure to many readers, but not to the gang from Van Horn. Angell’s dinner mates Jim and Dana must have been of my parents’ generation since they had heard Walt Lochman on the radio. The “Bill” at Bryant’s was not of that generation – Angell later reveals that it was Bill James, a Royals fan from Lawrence, Kansas, “a lanky, bearded, thirty-two-year old baseball scholar who writes the invaluable Baseball Abstract…notable for its dazzling use of statistics…and Jamesean elucidations.” James had self-published his first abstract just three years earlier. James is still going strong today as a senior statesman in the world of sabermetrics, a name he coined. I bought another copy of Late Innings to give to Bill at our next lunch so he could see how his dad was part of a conversation that included two icons of baseball journalism.

Fish Fry and Walt Lochman: My next stop was the internet and the ever-reliable Google. I found a few articles, but I was especially intrigued by a reference to a sound recording of a Blues game archived at the Marr Sound Archives in the Miller Nichols Library at UMKC. I got in touch with Chuck Haddix, the Director at Marr, to see what he might have. Many of you know Chuck through his on-air name of Chuck Haddock, the deejay/historian who plays great music on Friday and Saturday nights on Fish Fry on public radio. Chuck found several recordings in his archives and invited Bill and me to come over and take a listen. The recordings are on 16-inch acetate discs originally cut in the KMBC radio studio during the programs. We listened to digitalized versions prepared by the archives staff and heard parts of Blues games and some of Lochman’s daily 5-minute sportscasts. Chuck also came up with some real gems from the sister archives on the print side of the Miller Nichols Library (the Arthur Church/KMBC Radio collection on Walt Lochman and Olympics of the Air).

Walt Lochman, KC Baseball Pioneer: Walt Lochman started in radio in 1927, working for various stations in the Midwest as a singer, announcer, talk show host and administrator. He had an accidental opportunity to broadcast a 1929 World Series game when the national feed was lost and he recreated the game from the incoming Western Union ticker. He was interested in sports broadcasting, and a family situation in 1935 provided additional motivation. His Uncle Lou had suddenly lost his vision at age 65 and complained that play-by-play coverage on the radio was poorly done. Lochman approached Blues’ owner Johnny Kling to get permission to broadcast the games. Baseball owners had been hesitant to employ radio because they thought it would keep fans away from the park (just as they later were slow to embrace TV). Kling was wary, but agreed to a 10-game test. It was a smashing success as attendance increased dramatically from the interest generated by the radio coverage. Lochman would go on to broadcast over a 1,000 games through 1942.

Lochman started as a novice, but he talked to Uncle Lou after broadcasts on how he could improve. Lochman said he kept his Uncle Lou in mind when broadcasting, striving to give him the nearest possible complete picture of the action on the field. He developed a pattern that became very popular with the fans, and annual attendance at the games grew from 100,000 to over 300,000. His colorful accounts also worked for other sports, and he became a major radio voice for Big Six football plus hockey, basketball and boxing. He had a daily 5-minute sportscast heard by almost half of the radio market. His ratings for Big Six football were always much higher than other stations carrying the same game. In a 1936 “Wheaties Poll”, he was named the most popular sportscaster in the country. In 1940, he was named the top minor-league announcer in the nation in a poll conducted by The Sporting News. Lochman moved up to the major leagues to broadcast the White Sox in 1943 and 1944. He then returned to the Midwest for a variety of radio positions until his death in 1954.

Walt Lochman, The Voice: At the Marr Archives, there are no recordings for home games because those were broadcast from the stadium rather than the studio. But there are recordings of some away games because those were broadcast in the studio based on telegraph updates. In those days, stations rarely went on the road to broadcast – the cost of leasing lines with voice capacity for a ball game was prohibitive. So the practice was for a Western Union operator to sit in the studio and convert the Morse Code transmission and feed the info to the announcer. From 1935 to 1954, “Silent John” Gibson was the telegraph operator for Blues games and was considered one of the best telegraph sports reporters in the nation. Lochman broadcast as if he was at the game, and crowd and bat noises were sometimes added to enhance the effect. We know that Lochman used such sound effects, but none are on the recordings we heard. This may be because they were on a different microphone or that sound effects came along at a later date.

Lochman also became friends with an announcer who reenacted Cubs games off of the teletype for a Des Moines station. In 1937, that announcer went to California to broadcast Cubs spring training reports back to Des Moines. While there, he took a screen test and decided to give up baseball. Ronald Reagan was now in Hollywood.

Bill and I listened to a recording with a couple of innings of a Blues game at Indianapolis in 1940. Phil Rizzuto was in the game and made an error. A solo homer was hit by the Blues’ Blacky Caldwell. I checked out Blacky online at Baseball Reference, and he only had one homer in his career. It was captured on the air, via teletype, by Walt Lochman.

We also listened to excerpts from some of the 1941 daily sportscasts: a report on Lochman’s discussion with Johnny Evers (of Tinker to Evers to Chance), including the effect of the military draft on players and whether or not Mel Ott could have another good year at age 32, like had been the case for Ruth, Cobb and Hornsby; recap of a game where Johnny Vander Meer was the losing pitcher [known forever as the only pitcher to hurl back-to-back no-hitters]; an upcoming broadcast of the Blues and the Toledo Mud Hens [the team of Klinger on MASH]; ads by Rothschild’s and Studebaker; and talk of the ongoing record hitting streak by Joe DiMaggio. Soon after the broadcast, Joe’s 56-game streak ended on July 17. For some historical perspective, Bill and I were born a few weeks after Joe’s streak ended.

Kansas City Blues in 1939 and 1940/Phil Rizzuto: In 1937, the Blues became a farm team of the Yankees. This brought some very good players to the Blues, and the 1939 team is considered one of the best minor-league teams of all time. Their record was 107-47. Vince DiMaggio hit 46 homers. A detailed account of that season is at this link. The Blues repeated as champs of the American Association in 1940. Phil Rizzuto was the MVP of the league and was also named Minor League Player of the Year by The Sporting News. “Scooter” Rizzuto got his nickname from his Blues teammate Billy Hitchcock. He moved up to the Yankees in 1941 where he had a ringside seat to DiMaggio’s hitting streak.

Phil Rizzuto – 1940

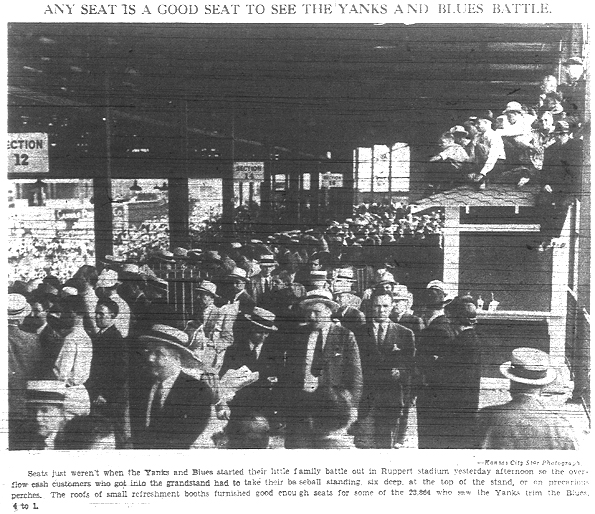

Kansas City Blues in 1939/Lou Gehrig: The Blues 1939 regular season took a break on June 12 for an exhibition game against the parent Yankees. The buzz for the game was strong as fans knew it was likely the last season for Lou Gehrig. Earlier in the season, on May 2, Lou took himself out of the lineup after having played in 2,130 consecutive games. The “Iron Horse” knew something was amiss with his skills and did not want to hurt the team. He never played in another major league game, but he continued to travel with the team and was in Kansas City for the exhibition game. He did not want to disappoint the fans, and so he played for three innings, his last game ever. The next morning, he left KC’s Union Station for the Mayo Clinic where it was determined he had ALS. The crowd overflowed the stadium to see Lou’s last game (“standing six deep at the top of the stand, or on precarious perches. The roofs of small refreshment booths…”):

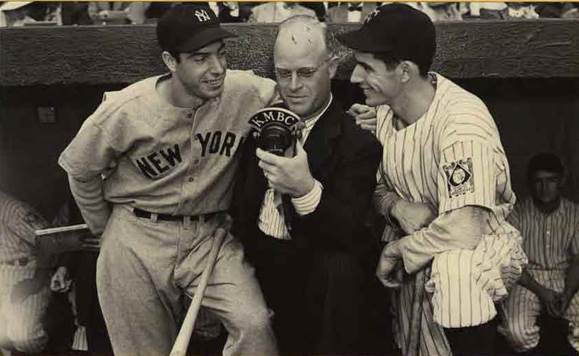

Here is Walt Lochman at that game with the center fielders for the teams, Joe DiMaggio of the Yankees and his brother Vince DiMaggio of the Blues:

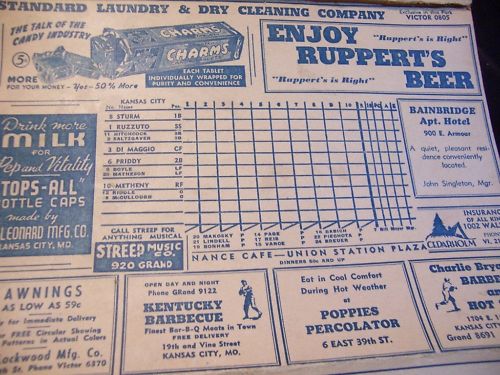

And a scorecard from the game:

There are some interesting ads on this scorecard. On the bottom row, two barbecue dynasties are represented. The “Kentucky Barbecue” at 19th and Vine was later sold to George Gates, and his son Ollie continues in the business today. “Charlie Bryant’s Barbecue” would later be sold to his brother Arthur who moved it to 1727 Brooklyn where it still operates today (and hosted Roger Angell and Bill James in 1980 as related above).

“Ruppert’s Beer” was owned by Jacob Ruppert, the then-owner of the Yankees and the Blues. The ballpark in Kansas City had been called Muehlebach Field since it was built in 1923, named after the beer sold by team owner George Muehlebach. When the Blues began their affiliation with the Yankees in 1937, the park was renamed Ruppert Stadium. From one beer baron to another. In 1943, the name was changed to Blues Stadium.

Hall of Fame Players at Ruppert Stadium in 1939: The Yankee team in Kansas City with Lou Gehrig that day went on to win the 1939 World Series. It included Hall of Famers Gehrig, Bill Dickey, Joe DiMaggio, Lefty Gomez, Joe Gordon and Red Ruffing. NY manager Joe McCarthy and owner Jacob Ruppert are also in the HOF. The KC lineup had one Hall of Famer – Phil Rizzuto. The stadium was also the home of the Kansas City Monarchs who fielded four Hall of Famers in 1939: Turkey Hearnes, Hilton Smith, Willard Brown and Andy Cooper. The more famous Satchel Paige had a sore arm that year and played and managed a barnstorming team. Satch joined the Monarchs in Ruppert Stadium in 1940.

Coming Hot Stove Attractions: Mickey Mantle with the Kansas City Blues in 1951; “Who’s on First” – who is the best all-time first baseman?

Go Royals! Sure looking good at home at Kauffman Stadium (not named after a beer baron).