Looking back 75 years ago to 1947…

On April 15, Jackie Robinson broke the color line in the National League. On June 11, Julia Lee recorded her #1 R&B hit “(Opportunity Knocks But Once) Snatch and Grab It.” On July 5, Larry Doby broke the color line in the American League. I’ll talk about the baseball first, and then we’ll meet up with Julia Lee in Lonnie’s Jukebox.

Moonwalking: I borrowed the title of this post from President Bob Kendrick of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum. On Bob’s award-winning podcast series (Black Diamonds), his episode on Larry Doby is titled “The Second Man On the Moon,” a recognition that the memory of Larry Doby in baseball history is akin to the fate of Buzz Aldrin, the second man to walk on the moon.

Almost everyone knows that Neil Armstrong was the first man to walk on the moon. And that Jackie Robinson was the first to break the color line in baseball. But far fewer know the men who were second in those landmark roles. For the moon, it was Buzz Aldrin who touched the surface 19 minutes after Armstrong. In baseball, it was Larry Doby who took his first at bat 11 weeks after Robinson.

Robinson and Doby both debuted in 1947, Robinson on April 15 and Doby on July 5. Since Robinson played for the Brooklyn Dodgers in the National League, Doby had the distinction of breaking the color line in the American League with his Cleveland Indians.

In MLB games on April 15 this year, there was a lot of (well deserved) fanfare in honor of the 75th anniversary of Robinson’s inaugural appearance for the Dodgers. This coming July 5 will not go unnoticed, but any fanfare for Larry Doby will be modest. Some sportswriters will write columns. Broadcasters will hopefully note the history during games on July 5. It would be great if 92-year-old Buzz Aldrin released a statement.

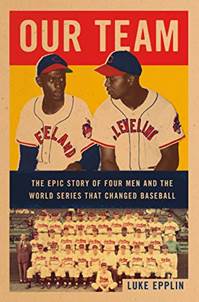

Over the past year, Doby has received good publicity in baseball circles because of an acclaimed book, Our Team: The Epic Story of Four Men and the World Series That Changed Baseball. Written by Luke Epplin, the book tells the story of the 1948 World Champion Cleveland Indians, spotlighting team owner Bill Veeck and three players (Larry Doby, Bob Feller and Satchel Paige). It’s an entertaining read.

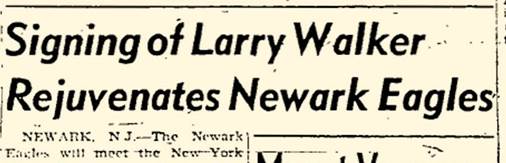

Larry Doby and the Newark Eagles: Doby was a star in basketball and baseball at his New Jersey high school. In the spring of 1942, the 18-year-old Doby was recruited by Abe and Effa Manley to play for their Newark Eagles in the Negro National League. He played under the alias Larry Walker to maintain his amateur status because he hoped to also play college basketball.

With high school graduation still weeks away, Doby played his first professional game on May 31, 1942. He hit well that season for the Eagles, but all plans were put on hold when he was drafted into the Navy in 1943.

The War: Although they did not cross paths in the war, three of the men in Our Team ended up in the Pacific Theater – Doby and Feller in the Navy and Veeck in the Marines. Feller had been the top pitcher in the majors for several years, and the war cost him three years in his prime (1943-1945). Doby lost most of 1943 and all of 1944 and 1945. Veeck suffered an injury that cut short his time in the service. Jackie Robinson had also served, but was out in time to play the 1945 season with the Kansas City Monarchs.

While Doby (below) was stationed in the Pacific in October of 1945, a fellow sailor came joyfully running up to him. With the war over, Doby assumed it was news about going home. The sailor said, “No. But when we do, maybe you can get into the big leagues. The Dodgers have just signed Jackie Robinson!”

Transition Year of 1946: As the 1946 baseball season got underway, Jackie Robinson began play for the Dodgers’ top farm team in Montreal.

Bill Veeck had sold his minor league team and was itching to buy a Major League team. He got his wish in June of 1946 when he purchased the Cleveland Indians.

Larry Doby, hoping to follow in Jackie Robinson’s footsteps, returned to the Eagles to showcase his talent for Major League scouts. He finished the 1946 season with a .360 average and was among the league leaders in doubles, triples and homers.

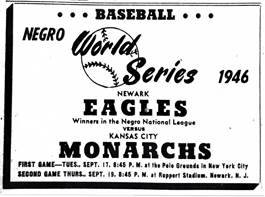

Satchel Paige was with the Kansas City Monarchs who won the Negro American League. Doby’s Newark Eagles won the Negro National League, setting up a 1946 Negro Leagues World Series with seven future Hall of Famers (Newark – Leon Day, Larry Doby, Monte Irvin and Biz Mackey; KC – Willard Brown, Satchel Paige and Hilton Smith). The owners of both teams are also in the Hall of Fame – Newark’s Effa Manley (the only woman in the Hall) and the Monarchs’ J. L. Wilkinson.

After six games, the teams were tied at three games each. Then a strange thing happened. Satchel Paige was scheduled to pitch Game 7 and did not show. The Eagles won and took the Series.

Satchel had left the Monarchs to begin a storied barnstorming tour against a team assembled by Bob Feller. When Feller had returned from the service, he persuaded MLB Commissioner Happy Chandler to allow MLB players 30 days for barnstorming in the off-season. They had previously been limited to 10 days because previous Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis did not want fans seeing Black teams beating white teams. Feller argued that many players had lost money because of the war and needed barnstorming to catch up. Chandler said yes.

Feller leased two planes, one for his all-stars and one for Paige’s all-stars (below). The Feller-Paige tour was a resounding success. Larry Doby also barnstormed, but with a team assembled by Jackie Robinson.

1947 – Integration: Jackie Robinson opened the 1947 season with the Brooklyn Dodgers on April 15. The decades of MLB segregation were finally over.

Dodgers GM Branch Rickey also had his eyes on other Black players. Some were already in the Dodgers farm system, including Roy Campanella who Ricky had asked to scout the 1946 Negro League World Series. Campanella’s top two recommendations were Larry Doby and Monte Irvin of the Newark Eagles.

Doby began the 1947 season with the Eagles, but both Branch Rickey and Bill Veeck were showing interest. When Rickey heard that Veeck was in pursuit, he backed off. Rickey felt if another team signed a Black player, especially a team in the American League, it would give Rickey some cover and also help advance baseball integration

Veeck did not follow the Rickey model on dealing with Negro League teams. Rickey had refused to compensate the Negro League owners when he raided their players. The owners had little leverage because the Black community was excited to see Black players in the majors. Veeck had a long appreciation for the Negro Leagues and so paid the Newark owners $15,000 for Doby’s contract. Not a huge amount of money, but it was an important gesture.

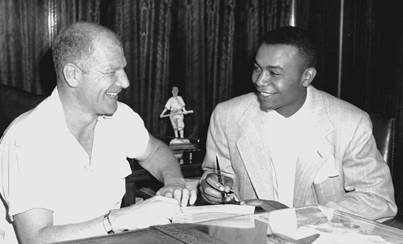

Doby played his last game for Newark on July 4 and headed to Chicago where the Indians were playing the White Sox. On the morning of July 5, he signed his contract with Veeck (above), and then went to Comiskey Park where he met his (mostly unfriendly) teammates. He pinch hit in the game, breaking the color line in the American League. After the game, the Indian players went to the Del Prado Hotel. Except for Doby. He was taken to the DuSable Hotel, a storied Black hotel on the South Side.

Thus began the indignities. And just as Rickey had instructed Robinson, Veeck directed Doby to take such blows without fighting back – no arguing with umpires, no responding to racial slurs and taunts from fans and players, no fighting, no associating with white women, acceptance of local Jim Crow laws, etc. Doby often talked with Robinson by phone about the difficulties they faced, saying the two “kept each other from giving up.” Although Jackie got the publicity for how he was treated, Doby said it was no better for him: “It was the same thing I had to deal with. He was first, but the crap I took was just as bad. Nobody said, ‘We’re gonna be nice to the second Black.’”

Another issue for Doby was that he did not have a position to play. He had been a second baseman, but perennial all-star Joe Gordon had that job with the Indians. Veeck and manager Lou Boudreau thought that Doby’s speed could be better used in the outfield, but that would involve a learning curve. So Doby played little in 1947, and Veeck regretted that he had not first played Doby in the minors to give him the advance preparation that Branch Rickey had orchestrated for Jackie Robinson.

1948 – The Pennant and a World Series: When Bill Veeck bought the Indians in 1946, he had a big star in Bob Feller, but otherwise not a championship mix. The team did not do well in 1946 (68-86), but Veeck’s promotional talent drew in over a million fans, almost twice the previous year and the first time ever that the Indians exceeded a million. The team got better in 1947 (80-74) and attendance jumped to over 1,500,000. In 1948, the team won the AL pennant (97-58) by beating the Red Sox in a one-game playoff. Attendance in 1948: 2,620,627!

One of the reasons for the big attendance number was Satchel Paige. Satch was disappointed that he was not the first to break the color line. Unfortunately, he had three strikes against him. Age. Price tag (he made good money as a top draw all over the country). Maverick tendencies (not likely to follow the rules laid down to Robinson and Doby by Rickey and Veeck). But Satch got his chance to play in July of 1948 when Veeck brought him in to bolster the pitching staff. It worked perfectly. Satch finished with a 6-1 record and a 2.48 ERA, but he may be most remembered for the crowds he drew for his starts – in one stretch of three starts, the attendance exceeded 200,000 (Cleveland Stadium held over 70,000). Below, former barnstorming opponents Bob Feller and Satch together with the Indians.

Another key to Cleveland’s success was a breakout year for Larry Doby. The Indians brought in Hall of Famer Tris Speaker to tutor Doby. Speaker was a great defensive center fielder and was on the only Indians team that had won a World Series, back in 1920. The tutoring worked. Doby blossomed as an outfielder and hit .301/.384/.490. He was on his way to his own Hall of Fame career.

The Indians beat the Boston Braves in the 1948 World Series, giving them their second title (they have not won since, the longest drought in MLB). Doby led the Indians in all major batting stats and became the first Black player to hit a homer in a World Series. Satchel Paige became the first Black pitcher to appear in a World Series.

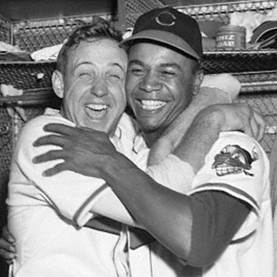

The most memorable photo of the 1948 Series was in the locker room after Game 4. Pitcher Steve Gromek had pitched a complete game for the Indians, taking a 2-1 win with Doby’s home run being the difference. Doby had also made two spectacular catches on long line drives to center field. In the post-game celebration, Gromek showed his appreciation by throwing his arms around Doby’s neck. This was one of Doby’s happiest moments in his career.

Integration had provided success stories in the first two years. Jackie Robinson had been instrumental in the Dodgers winning the NL pennant in 1947 (losing in the World Series). Larry Doby and Satchel Paige had major roles in Cleveland winning the 1948 AL pennant (winning the World Series). So all would now go smoothly, right?

Not So Fast: Jim Crow did not care who won the World Series. Nor did the owners of the other teams. Notwithstanding the success of the Dodgers and Indians, no other team had a Black player on the roster for Opening Day in 1949, and only the Giants did so later in the season (Monte Irvin, Doby’s teammate from the Newark Eagles, and Hank Thompson).

When Larry Doby went to spring training in Tucson in 1949, the team hotel was still off limits to him. Before the season started, the Indians played an exhibition game in Texas, and the local stadium would not allow Black players to suit up in the locker room. So Doby and Satchel Paige, joined by rookie Minnie Minoso, suited up at the hotel and went out to get a cab to the park. No cab would take them, so they walked the 1.5 miles to the game. Three future Hall of Famers.

These indignities continued for many years, and it was not until 1959 that all teams were integrated. Jim Crow lasted even longer, especially at spring training. This story is well told in After Jackie, a documentary released this month by the History Channel. The movie chronicles the battle for equality in the 1960s by Bob Gibson, Bill White and Curt Flood of the St. Louis Cardinals. The movie is available online here. Trailer here.

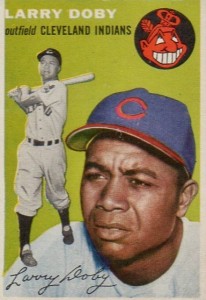

Doby’s Hall of Fame Career: Bill Veeck sold the Indians after the 1949 season, but the team he built continued its winning ways. Larry Doby remained with the team from 1949 to 1955, and during those seven seasons, the Indians won another pennant and finished in second place four times. Doby was an all-star each year.

The big obstacle for the Indians was the New York Yankees (Mantle, Berra, etc.) who won the AL pennant and the World Series five years in a row. The Indians ended the Yankees’ streak in 1954 with an astounding 111-43 season, the best winning percentage (.721) since 1909. No team has topped that percentage since. [Trivia: Seattle won more games in 2001, but the season had been increased from 154 to 162 games. Seattle’s 116-46 record was a winning percentage of .716).

The 1954 season was also Larry Doby’s best. He led the league in homers and RBIs and finished second to Yogi Berra in MVP voting. Unfortunately, the Indians fell flat in World Series and were swept by the New York Giants (this is the Series when Willie Mays made “The Catch”).

Doby was traded to the White Sox in 1956 and then returned to the Indians for 1958. He began the 1959 season with Detroit and was traded to the White Sox where the new owner was his old friend Bill Veeck. That was Doby’s last MLB season.

After his playing days, Doby held various scouting and coaching jobs and managed teams in Venezuela. In June of 1978, Bill Veeck fired White Sox manager Bob Lemon and replaced him with Doby. This again made Doby a “second” trailblazer as he became the second Black to be an MLB manager. The first had been Frank Robinson in 1975. Doby was not rehired as manager for 1979, but stayed on as the batting coach.

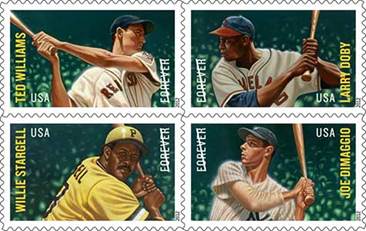

Doby’s career in baseball was honored with his (too long delayed) induction into the Hall of Fame in 1998. He died in 2003 at the age of 79. He was one of four iconic baseball legends featured in the MLB All-Stars stamps issued in 2012.

The Green Book Life: In the days of Jim Crow, Black baseball players often stayed at hotels listed in the Negro Motorist Green Book. Here is a KC listing from the Green Book:

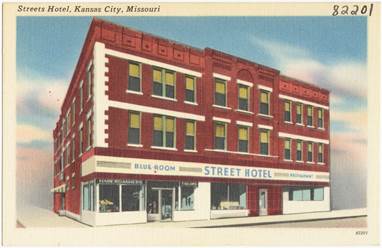

The Street Hotel (a/k/a Street’s and Streets) was popular with the Kansas City Monarchs who had some advantages that white players did not have. Buck O’Neil devotes a whole chapter in his autobiography on this topic. An excerpt:

“At 18th and Vine, you couldn’t toss a baseball without hitting a musician, and you couldn’t whistle a tune without having a ballplayer join in. Baseball and jazz, two of the best inventions known to man, walked hand in hand along Vine Street. We had Satchel Paige and Satchmo Armstrong; Blues Stadium, where we played our ball, and the Blue Room at the Streets, where we had a ball…staying at the Streets Hotel at 18th and Paseo and coming down to the dining room where Cab Calloway and Billie Holiday and Bojangles Robinson often ate…’Good morning Count,’ I’d say. ‘Good evening, Buck,’ Mr. Basie would say. As somebody once put it, ‘People are afraid to go to sleep in Kansas City because they might miss something.’”

Buck spoke of at least 50 nightclubs in the area by the Street Hotel and name-checked some of the artists he saw: Charlie Parker, Duke Ellington, Jay McShann, Big Joe Turner, Dinah Washington, Fats Waller, Lester Young and Julia Lee (more on Julia in Lonnie’s Jukebox).

Buck had similar favorite hotels in Chicago (Vincennes), Cleveland (Majestic), and D.C. (Dunbar). It’s likely Larry Doby stayed at the Street Hotel in Kansas City when his Newark Eagles came to town to play the Monarchs. When Doby first started playing for the Indians, his residence in Cleveland was the Majestic Hotel, a social center for Blacks in the city and home to traveling entertainers and athletes.

The American League arrived in Kansas City in 1955, and many visiting teams stayed at the Hotel Muehlebach. But not Larry Doby and other Black players. The restriction was eventually dropped by the Muehlebach when the Yankees insisted that Elston Howard, a former Negro Leaguer, stay with the rest of the team. But that kind of leverage did not work with a good portion of Kansas City hotels, restaurants and bars that would remain segregated until the 1960s.

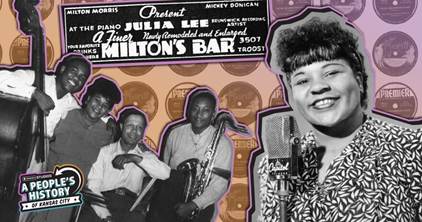

Lonnie’s Jukebox – Julia Lee Edition: When Buck O’Neil spoke of the close relationship of baseball and jazz, he liked to highlight Julia Lee and Frank Duncan Jr. who married in 1919. Julia was a teenager starting a career as a jazz and blues singer/pianist and Duncan was a baseball catcher who would soon be playing for the Kansas City Monarchs. When Lee played at all-white clubs, Duncan could not be in the audience, so he carried in an empty instrument case and pretended to be in the band so he could see his wife perform.

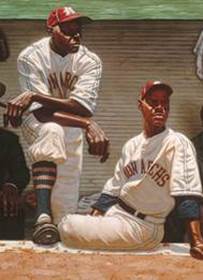

Duncan and Lee divorced after nine years, but their union produced a son (Frank III) who played for the Monarchs in 1941. Frank III pitched a game that year with his dad behind the plate, forming what is believed to be the first father-son battery in professional baseball. Frank Duncan Jr. played in the Negro Leagues for 25 years and was the Monarchs manager from 1942 to 1947. He twice led the team to the Negro League World Series, winning in 1942 over the Homestead Grays and losing in 1946 to Larry Doby’s Newark Eagles. Below, from a famous Kadir Nelson painting, Buck O’Neil (left) and Frank Duncan Jr.

From the 1920s to the 1950s, Julia Lee was one of the most popular entertainers in Kansas City. She would likely have become more nationally known if she had been willing to tour or move to a bigger city like some other KC jazz and blues legends (e.g., Jay McShann, Mary Lou Williams and Charlie Parker). But she did not want the Green Book life of searching for friendly places or worrying about bad cops and racists on the road. She also had a tragic experience on tour in 1930 when a band member was killed in a car accident. When flying became available, she said she would do it if she could keep one foot on the ground.

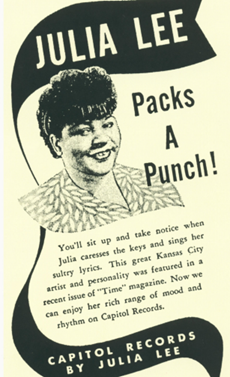

Lee’s first decade of work coincided with Prohibition, but there was no shortage of places to sing in Pendergast-era Kansas City. Starting about 1935, she became a fixture at Milton’s at 3507 Troost. She got a big break in the 1940s when former Kansas Citian Dave Dexter, a record producer at Capitol Records, convinced the label to record her. She went to Los Angles (by train) and recorded with groups of all-star musicians assembled by Dexter (recording as “Julia Lee and Her Boy Friends”). Although she had some recording success, her primary work over the years continued to be performing for her fans at the Kansas City clubs. She was still attracting good audiences at the High-Ball Lounge on 12th Street when she died in 1958 at the age of 56.

The details of her life and music have been captured in a superbly produced and edited podcast released earlier this month by KCUR. The piece includes interviews with Chuck Haddix (host of KCUR’s Fish Fry and a big fan of Lee) and Julia Lee’s grandson Julian Duncan (named after her). It is part of the station’s excellent podcast series “A Peoples History of Kansas City.” At your leisure, I recommend a listen – a wealth of information and music clips are efficiently packed into 34 minutes of audio (click here). A 4-minute on-air piece ran on NPR’s Weekend Edition (click here).

And now the fun part. Julia Lee was a master of the double entendre. As phrased by KCUR, Lee reigned over Kansas City jazz clubs singing raunchy songs that Lee says “her mother taught her not to sing.” Several other words come to mind. Risqué. Dirty. Salty. Sultry. Fun. One of the best examples is…

“(Opportunity Knocks But Once) Snatch and Grab It.” (1947). Jackie Robinson and Larry Doby were in the majors and Lee had her first hit for Capitol. The lyrics were considered too risqué for airplay, but jukebox play drove sales (more than 500,000 copies). The record was #1 for four weeks during November and December of 1947 on Billboard’s chart of “Most Played Jukebox Race Records” (a precursor of the R&B chart). The song continued at #1 into 1948 for eight of the first ten weeks.

“King Size Papa” (1948). Lee was out of the #1 spot for only one week before this record reached #1 and stayed there for nine weeks. It was also not subtle on the raunchy spectrum.

This song has a great story from Milton Morris who owned Milton’s where Lee performed for years. He claims to have made a drunken call one night that made its way to Harry Truman and led to Julia Lee and her favorite sideman, drummer Baby Lovett, performing at the 1949 White House Correspondent’s dinner. Milton Morris also attended and gave this colorful report:

“Truman’s got this bar at the White House. They’ve got Secret Service men. They’ve got Danny Kaye, Arthur Godfrey, Julia Lee, Baby Lovett and myself and Truman. And he’s still drinking Pendergast whiskey. So I have a few shots, and I say to myself, ‘Look at this little Jew from an orphan home, standing here with the President of the United States. I wonder what words of wisdom he’s got to say.’ He turns around to me, and he says, ‘Milt, they still got all those whores down around 14th and Cherry?’”

Truman was no doubt aware of Lee’s double-entendre fame. And she did not disappoint, singing “King Size Papa” for Truman and the correspondents. The Kansas City Star reported that she was called upon to do two encores.

Milton Morris Trivia: Starting in 1960, Morris ran for governor multiple times. He said he had a written contract with Count Basie to play at the inaugural if he won. His platform was simple: Legalize casino gambling and horse racing and set a 4 a.m. closing time for cabarets. A man ahead of his time.

Billboard Chart Trivia: Both of Lee’s #1 hits led the “Most Played Jukebox Race Records” chart. At the time, this was the only Billboard chart for music marketed to African-American audiences. In May of 1948, an additional chart was added that tracked retail sales of such music. Below is the chart for the first week of retail charting (May 14, 1948). “King Size Papa” is #7.

In 1949, Jerry Wexler was a writer and editor for Billboard. He correctly thought the term “race” was inappropriate, and Billboard agreed to change the name of the chart to “Rhythm and Blues” (a/k/a “R&B”). This was a prescient decision as record buyers would soon be buying based on what they liked, not limited by the color of the artists, and this crossover was an early sign of the birth of rock ‘n’ roll. And Wexler was in the middle of it. In 1953, he joined Atlantic Records and produced hits for such artists as Ray Charles, the Drifters, Wilson Pickett and Aretha Franklin.

Now back to more Julia Lee music…

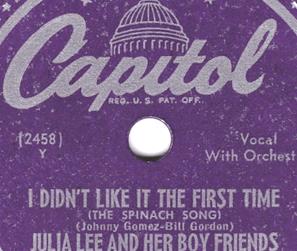

“I Didn’t Like It the First Time (The Spinach Song)” (1949). The song opens with a recitation of the vitamin values of spinach, but listeners will find other meanings. Marijuana was a possibility, but it was likely more risqué as suggested by Billboard’s review: “A happy double-meaning romper in the spirit of ‘Snatch and Grab It’ and ‘King Size Papa.’” The record peaked at #4.

“You Ain’t Got It No More” (1949). Automobile metaphors…you are in low gear, your rear end is shot, your tank is empty…you ain’t got it no more.

The last selection for this edition of Lonnie’s Jukebox is also the last Julia Lee release by Capitol Records, aptly titled…

“Last Call (For Alcohol)” (1952).

After her hits in the late 1940s, Lee’s record sales decreased. She was a vintage act in the jazz and blues tradition that helped birth rock ‘n’ roll, but the record sales for the new genre would belong to the next generation . Not that she has been forgotten. There is a ton of info online about her music and life. In 1990, her “Snatch and Grab It” was the opening song for the Robin Williams film Cadillac Man. In 2010, some 63 years after it was recorded, “Snatch and Grab It” was used in an NFL ticket exchange ad (click here). Many Julia Lee selections are available on YouTube and Spotify.

And as the KCUR podcast reminds us, Julia Lee was more than just her songs. She was a trailblazer for Black female musicians, forging a career on her own terms. She snatched and grabbed it. No double entendre intended.

End Note: Larry Doby’s Cleveland team will be in Kansas City to play the Royals during the week of the 75th anniversary of Doby’s first game. Doby’s team is of course no longer known as the Indians – as of this season, they are the Guardians. Chief Wahoo has been retired.

Royals v. Guardians, July 8-10. Go Royals!