Remember the Kansas City A’s? Charlie Finley? Campy Campaneris? Blue Moon Odom? Paul Lindblad? George Wallace? Bull Connor? Bear Bryant? They are in the cast of characters who inhabit my 19th annual message for Martin Luther King Jr. Day. I hope you have the opportunity to read this (somewhat long) story as we get ready to celebrate the holiday.

I began writing an annual message for the MLK holiday back in 2002. The message that first year was about Martin Luther King’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” which was published in April of 1963. The letter was written by King while he was imprisoned for leading civil rights demonstrations. Why was King in Birmingham? In his words:

“Birmingham is probably the most thoroughly segregated city in the United States. Its ugly record of brutality is widely known. Negroes have experienced unjust treatment in the courts. There have been more unsolved bombings of Negro homes and churches in Birmingham than in any other city in the nation. These are the hard, brutal facts of the case.”

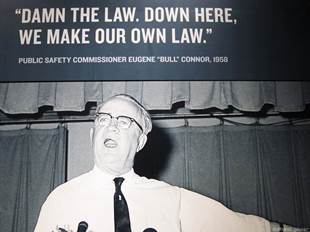

In May of 1963, three weeks after King’s letter, Birmingham public safety commissioner Bull Connor unleashed dogs and fire hoses on demonstrators. In September, four girls were killed by a bomb at the 16th Street Baptist Church. Birmingham earned a nickname: “Bombingham.”

For this year’s message, I am returning to Birmingham, but with a story from the year after those historic events. It’s a baseball story. And a civil rights story.

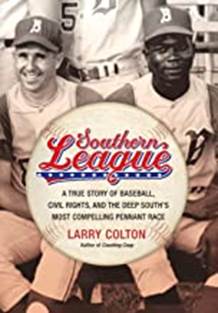

My thanks to Hot Stove reader David Matson who suggested that I read Larry Colton’s 2013 book Southern League. It was a valuable resource for what follows.

Birmingham Baseball – Before 1963: Rickwood Field in Birmingham was the home of two successful teams before 1963 – one black and one white. Both teams played for decades, but each was gone by the early 1960s, although for radically different reasons. However, the reasons dated back to the same event in 1947 – Jackie Robinson’s breaking of the color line.

[Ballpark Trivia: Rickwood is still in use and is the oldest baseball park in the country. Built in 1910, it predates Fenway (1912) and Wrigley (1914).]

Birmingham Barons (White): The Barons played minor league baseball in Birmingham since before 1900. They not only followed the tradition of segregated baseball, they followed the letter of the law. Jim Crow had been codified in Birmingham for years, and one ordinance was known as the “Checkers Rule”: “It shall be unlawful for a Negro and a white person to play together or in company with each other in any game of cards, dice, dominoes, checkers, baseball, softball, football, basketball or similar games.”

In the 1920s and 1930s, the play-by-play radio announcer for the Barons was a man with a booming voice. He became very popular for his chatter and re-creation of away games based on wire reports. This prompted his fans to nickname him “Bull.” His given name was Theophilus Eugene Connor. That would be Bull Connor who parlayed his celebrity into politics, most infamously as the public safety commissioner of Birmingham.

There was a bump in Bull Connor’s political career. He was caught with his secretary in a hotel room in December of 1951, and the court case and news coverage led to his not running in 1952. In his absence from the city commission, the Checkers Rule was overturned. This paved the way in April of 1954 for two major league exhibition games at Rickwood Field. The rosters were integrated – Jackie Robinson’s Dodgers played Hank Aaron’s Braves.

The segregationists seethed. They gathered petitions for a referendum and campaigned with the slogan “Keep Baseball White.” Just two months after Robinson and Aaron had played at Rickwood, the Checkers Rule was reinstated. In 1956, Connor won his seat back, promising that the Checkers Rule would stay in place. The voters were willing to look the other way on Bull’s sex scandal, so long as he was a good segregationist.

In 1959, the last major league team to integrate ended its holdout. Boston owner Tom Yawkey finally added a black player to the Red Sox roster. In November of 1961, the major leagues decreed that their minor league affiliates would all need to do the same. Many teams in the South would not go along. Albert Belcher, the local owner of the Birmingham Barons, was pressured by Bull Connor to fold the team, saying “We cannot allow the mongrelization of our great national pastime.” Also, the Checkers Rule was still in place, leaving Belcher with no real option. The Barons and its league, the Southern Association, collapsed.

Birmingham Black Barons: The “Black” was part of the official team name. It was not unusual for a Negro League team to adopt the name of the white counterpart in a city. The most incongruous was Atlanta where the team names were the “Crackers” and the “Black Crackers.” The Black Barons were formed in 1920 and played in various Negro Leagues over the years. Satchel Paige pitched for the Barons from 1927 to 1930. In the 1940s, the team won the pennant and advanced to the Negro League World Series three times, each time losing to the legendary Homestead Grays.

In the last trip to the Series in 1948, the lineup included rookie Willie Mays. He also played in 1949 before being signed by the New York Giants. Below, Willie in his Barons uniform.

By 1960, the Negro Leagues were fading fast as the good young players followed the path of Jackie Robinson. The Barons became primarily a barnstorming team and folded for good in 1962.

Birmingham Baseball – 1963 (Not): The city had no professional baseball in 1963, but political changes during the turbulent year opened up the possibility for 1964. The voters approved a change in the form of government that abolished Bull Connor’s public safety office. Bull then ran for mayor and lost. But before the new officials were sworn in, Bull led his notorious attacks with dogs and fire hoses on demonstrators. Soon after Connor was gone, the new council repealed the Checkers Rule.

Baseball Returns to Birmingham – 1964: The local law had changed, but who would want to have a team in “Bombingham”? Especially in 1964. The KKK had a strong presence in the city and was implicated in the church bombing. Alabama Governor George Wallace was running for president vowing “segregation forever.” In the wake of President Kennedy’s assassination, President Johnson was pushing for the passage of a civil rights law. The atmosphere was incendiary. It was potentially dangerous to be in the South (sadly proven two months into the baseball season when three civil rights workers were killed in Philadelphia, Mississippi).

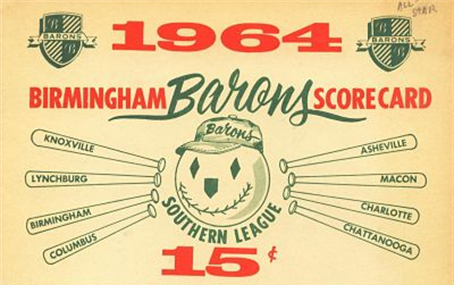

Former Barons owner Albert Belcher was willing to risk fielding a team. Major league teams were hesitant, but in a lucky turn, Charlie Finley was a native of Birmingham. He had even been a batboy for the Barons. Finley wanted to help his hometown, so Belcher’s Barons became an affiliate of the Kansas City A’s and joined the AA level Southern League.

Belcher refurbished Rickwood Field and personally removed the chicken-wire fence that had been used to divide black and white fans. In prior years, black fans at Barons games were required to sit far from home plate behind the chicken wire – some whites called it the “coal bin.” The policy was reversed for the few white fans who came to Black Barons games. Going forward, the players and fans would be integrated.

Not everyone was pleased. Belcher got phone calls (“If the n—–s play, somebody’s gonna die”). There was a bomb threat for opening day. Two days before the season started, Belcher received a late night visit from the local imperial wizard of the Ku Klux Klan. It was made clear that integration of baseball was not popular with many locals, but the Klan had decided not to fight this particular battle. The wizard was not personally “coming out to watch no n—–s less’n you promise one of ‘em gets hit in the head.” The good news: there would be no cross burnings at Rickwood Field.

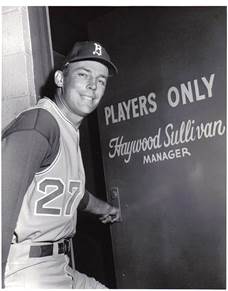

1964 Roster: Finley promised to stock the roster with top prospects from the A’s. He wanted Birmingham to have some good moments in what was otherwise a tense atmosphere in the city. Finley also made a wise decision in his choice of manager. Haywood Sullivan was from Dothan, Alabama, and was familiar with the racial issues. Sullivan had played four years with the Red Sox and then three with the A’s from 1961 to 1963. It would be his first managerial assignment.

Some worried that Finley and Sullivan, both Alabama natives, might not be receptive to black players on the team. There was no need to worry. There were five black players on the twenty-two man roster on opening day.

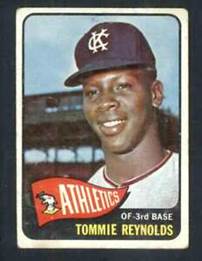

When the season started, Finley separately met with the black players, warning them about the treatment they would receive from some fans. He asked that they “stay cool” and be like Jackie Robinson. Campy Campaneris understood little English, but he got the message. Soon after the season started, two additional black players joined the team: Tommie Reynolds and Blue Moon Odom.

Tommie Reynolds: Reynolds was on the bubble of being a major leaguer. In 1963, he led the Midwest League in hitting and was called up to the A’s for some games at the end of the season. He hoped that he would move in 1964 to Dallas, the A’s AAA farm team. He especially did not want to end up in Birmingham. His A’s teammate Ed Charles had warned him of the indignities of playing in the South. The segregated facilities. Often no restroom to use. Flop houses rather than hotels. If you complained, you were a “troublemaker” and not destined to stay in baseball.

Reynolds soon met the issue as he headed for 1964 spring training in Florida. One night, unable to find a motel that would accept blacks, he slept in his car at a rest stop. He was awakened when something shattered his passenger window. The vandal fled, but Tommie found that a target had been drawn on the driver’s-side window. When he arrived at the team hotel, he was told by the desk clerk that blacks were not allowed. Welcome to the 1964 South.

Tommie started the regular season in KC, but only until holdout Rocky Colavito signed. He then went to the minors, but instead of Dallas, he became part of Finley’s promise to provide talent to Birmingham. Finley gave Reynolds the same speech he gave the other black players – act like Jackie Robinson. Finley told manager Haywood Sullivan that Reynolds was “exactly the kind of Negro that would be good for this team. Very mature, very serious.”

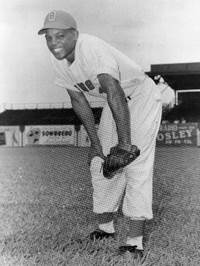

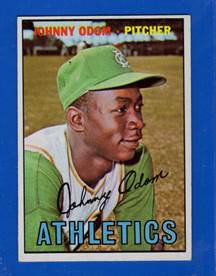

Johnny “Blue Moon” Odom: In 1964, there was no amateur draft. One of the best ways to lure young talent was to pay signing bonuses. Charlie Finley set his sights on two pitchers that he planned to send to Birmingham. One was Catfish Hunter who had been hurt the prior November in a hunting accident that cost him a toe. Finley signed him anyway, but Catfish had only limited play in the Florida Instructional League while he recuperated. He never made it to Birmingham and went straight to the majors the next year.

The other bonus baby was Blue Moon Odom, a poor kid from Macon, Georgia. Growing up, he knew that the best path to success for blacks in Macon was in either music or sports. He did not have the voice to follow Little Richard and Otis Redding who had gone to his high school, so he went with sports. He lettered in four sports and pitched eight no-hitters. Charlie Finley personally signed him, staying overnight at the Odom home the day before graduation. Under league rules, a player could not sign until he got his diploma. The story is that Finley paid $10 to sleep on the couch, outbidding another team by $2. The bonus to Odom was $75,000, the same as Catfish. Finley’s free spending was one of the reasons the amateur draft was established in 1965.

Finley promised Odom his first start would be in his hometown of Macon, one of the eight teams in the Southern League. The night was filled with hype as 7,000 fans overflowed the 5,000 seat stadium. Finley left his seat in the press box and became the only white face in the all-black section. Odom was hit hard and lost the game. The headline the next morning: “Moon Shot Fizzles Out.”

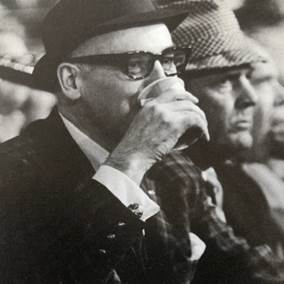

But Blue Moon had better luck in his first home game at Rickwood Field. He outpitched future Hall of Famer Ferguson Jenkins. Among the crowd of more than 5,000, Finley sat with Bear Bryant who had been a Barons fan for years. Below, the two at the game wearing their houndstooth hats.

[Bear Bryant Trivia: Bryant’s Alabama team in 1964 had Joe Namath, but no black players. This was not by his design. In his earlier job at Kentucky, he tried to get the school to be the first in the SEC to integrate the football team. He was turned down, just as he would be in his early years at Alabama. It’s hard to emulate Branch Rickey when George Wallace is the governor. In 1967, Bryant’s former team Kentucky became the first SEC team to field a black player. Bryant was still not free to do so, and the tide turned against the Tide as they dropped in the rankings. In 1970, Bryant invited USC to play at Legion Field in Birmingham. Alabama was trounced 42-21. USC was led by an all-black backfield of quarterback Jimmy Jones and running backs Clarence David and Sam “Bam” Cunningham. Many feel Bryant set up this showcase of an integrated team to make his case that Alabama should add black players. The very next year, he got the green light to do so. Former Alabama player Jerry Claiborne famously said (in the narrow context of college football) that the USC game did “more for integration in Alabama in sixty minutes than Martin Luther King Jr. did in 20 years.”]

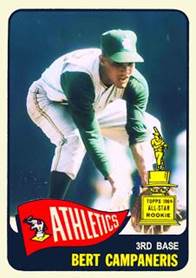

Bert “Campy” Campaneris: The standout star for the Barons was Cuban-born Campy Campaneris. He admitted to being scared as a black man in Birmingham. Afraid of being attacked after games, he ran the five blocks from Rickwood to his boardinghouse. He also had a language barrier. But he settled in, became a fan favorite and led the league in hits, stolen bases, runs, triples and hit-by-pitch. After being hit in the face by a pitch in a game, he became the first black to ever be treated at the University of Alabama-Birmingham Hospital.

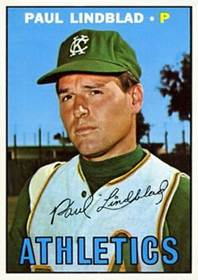

Paul Lindblad: One member of the roster had strong connections to Kansas City. Pitcher Paul Lindblad grew up in Chanute, Kansas, about 120 miles from KC. In 1962, he was the MVP of the Ban Johnson League, the premier amateur league in Kansas City. A good example of the quality of the league was the 1962 all-star game featuring four future major league pitchers: Lindblad, Steve Mingori, Steve Renko and Chuck Dobson. Lindblad signed with the A’s in 1963 for a $2,000 bonus.

Tension in Birmingham: There was now integration at Rickwood Field, but nowhere else in Birmingham. Not in most restaurants. Barely in the schools though Brown v. Board became law in 1954. Separate drinking fountains. No blacks on the police force. Low pay and low voter registration. And a host of other Jim Crow indignities, many legally mandated by ordinance.

The team’s first entry into Birmingham proved the point. When the bus arrived from spring training, it made an initial stop at the Gaston to let out the five black players. The motel often served as a temporary headquarters for Martin Luther King Jr. and had been bombed the previous year. It was located a few blocks from the 16th Street Baptist Church. The bus then took the white players to the (nicer) Tutwiler Hotel.

Soon after Blue Moon Odom joined the team, he was stopped late at night by a policeman who wanted to know why this “boy” was driving such a nice new car (a car Finley had arranged). When he realized this was the Barons’ bonus baby, the officer queried, “Boy, what’s a n—- like you going to do with all that money?” There was a reference to a turn-signal violation, but no charges. The real charge was of course “driving while black.” He offered some parting advice to Blue Moon: “This is Birmingham, Alabama. It’s real important you stay in the n—– part of town.”

For nine innings, Birmingham was integrated. Otherwise not at all.

Tension On the Road: When the Barons traveled to the other seven cities in the league, the black players were barred from the team hotels in six of them (the exception was Ashville). This was a big change for Paul Lindblad who had roomed with Tommie Reynolds on the road when they played in Burlington, Iowa, in 1963. The Knoxville boardinghouse for the black players had no AC or TV. The flophouse in Macon had holes in the wall. In Charlotte, five black players shared one room in a boardinghouse.

The white fans at Rickwood rarely taunted their home team players with racial invectives. In fact, Campy Campaneris was the crowd favorite. There was no such restraint on the road. The N word was commonplace. As were “monkey” and “banana.” A geographically-challenged fan told the Cuban Campy to go back to Africa.

The primary vitriol was directed toward Tommy Reynolds. He was darker skinned and a non-Latino. He was also hitting the cover off the ball – an effective response after being hit by olives thrown from the stands. Lynchburg was maybe the worst for Reynolds. The city was known for its “segregation academies” circumventing Brown v. Board. Some churches were no better. The Reverend Jerry Falwell preached that segregation was the Lord’s will, and in a criticism of Martin Luther King Jr., that “preachers are not called to be politicians but to be soul winners.” Irony noted.

On a road trip in July, the team bus stopped at a restaurant in northern Georgia. Black players usually stayed on the bus and ate take-out. On this stop, Haywood Sullivan took the black players in. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 had been signed into law earlier in the month. The owner said “the colored boys will have to eat out back.” Blue Moon Odom said “Anyone who don’t get back on the bus right now gonna have a problem with me.” Everyone left.

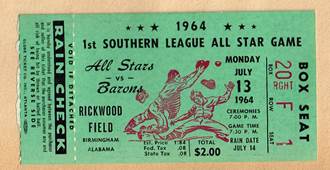

Pennant Race – A Loss: In the midst of the tension, the Barons were in first place most of the season. Finley had kept his promise to provide talent that might otherwise move up to the A’s AAA affiliate. This was important to Barons owner Albert Belcher who told reporters the he and Finley talked about “the importance of giving the city a winning team to help keep a lid on things around here.” Belcher was especially worried about summer demonstrations and what might happen in the fall as integration moved (glacially) forward in the schools. The talent put the Barons in first place in mid-season, which made them the host for the first Southern League all-star game.

So the hot-hitting Campaneris was staying in Birmingham for the pennant race. To take advantage of Campy’s popularity, a promotion was scheduled for August 2 for him to play all nine positions. But on July 22, A’s shortstop Wayne Causey was injured and Campy was called up to Kansas City. The next day, on the first pitch he saw in the major leagues, Campy hit a homer off the Twins Jim Kaat. He got another homer plus a single to lead the A’s to a 4-3 victory. Campy would not be returning to Birmingham.

Blue Moon Odom was not scheduled to move up to KC until Birmingham clinched the pennant. He was on a roll and would be instrumental in the tight race with Lynchburg. But Finley moved up the timetable and Odom missed two starts in Birmingham. In the first inning of Blue Moon’s major league debut, Mickey Mantle hit a 3-run homer. Odom gave up six runs in his two innings. But he did not return to Birmingham.

Tommie Reynolds did his best with spectacular hitting in September. Paul Lindblad showed his major league potential. Many other players were having good seasons. But with Campy and Blue Moon gone, the Barons relinquished their ninety-six days in first place, finishing one game behind surging Lynchburg. Belcher and Sullivan blamed the pennant loss on Finley’s roster moves.

Civil Rights – A Win: The Barons may have lost the pennant, but they won a key civil rights victory. It was not as early as the one by Jackie Robinson (who benefitted from playing his minor league season in Montreal). And it was not the first minor league team in the South to integrate. For example, Hank Aaron played at the Braves farm team in Jacksonville in 1953. Jim Crow still resided in Jacksonville, but that did not keep Aaron from having an MVP season (one pundit said Hank “led the league in everything except hotel accommodations”).

But Birmingham was unique, and not in a good way. It had been a rising economic powerhouse in the South, but it abruptly became isolated after demonstrations, fire hoses, attack dogs and bombs became the searing images of the city. The same vibe came at the state level with George Wallace as governor and the all-white football team that Bear Bryant was not allowed to integrate. [In contrast, the business community of Atlanta pushed to end Jim Crow, and the city was rewarded with the MLB Braves and NFL Falcons in 1966.]

The Barons of 1964 were not civil rights activists, but their actions proved a valuable lesson: You could integrate baseball players on the field and fans in the stands in the “most thoroughly segregated city” in the country (see MLK, “Letter from a Birmingham Jail”). The fans, black and white, shared the same restrooms and water fountains (many for the first time). If you could do that, why not lunch counters? Schools? Hotels? And everything else?

It would take many more years in some parts of the country, but the first steps must be taken by someone. Quite often, the trailblazers are from sports and music. Little Richard and Otis Redding sold millions of records to white teenagers – even George Wallace could not segregate the airwaves. And the competitive nature of sports eventually demanded that the best be allowed to play. When Hank Aaron told Martin Luther King that he was embarrassed that he had not been more visible on civil rights, he was told not to worry, “just keep hitting that ball. That was his job [for the cause].” King said of Jackie Robinson, “He was a sit-inner before sit-ins, a freedom rider before Freedom Rides.” Don Newcombe was told by King, “You’ll never know how easy you and Jackie [Robinson], and [Larry] Doby and Campy [Roy Campanella] made it for me to do my job by what you did on the field.”

So let’s praise the black players of the 1964 Barons for their brave presence in violent Birmingham and the Jim Crow cities of the Southern League. I believe there were seven on the team. Stanley Jones was a native of Birmingham and had pitched a no-hitter in 1958 for the Negro League Black Barons against the Kansas City Monarchs. Four players were black Latinos: Campy Campaneris (Cuba), Santiago Rosario (Puerto Rico), Woody Huyke (Puerto Rico) and Freddie Velazquez (Venezuela). Two players joining after opening day were Tommy Reynolds (San Diego) and Blue Moon Odom (Macon). I like to think of them as seven “Black Barons” following in the footsteps of Satchel Paige and Willie Mays.

Kudos also to Charlie Finley and Albert Belcher. They took big risks. Bomb threats. The threatened boycott that did not materialize. The uneasy peace with the KKK, an entity that was increasing its numbers to counter the growth of the Civil Rights Movement. And a pat on the back to Haywood Sullivan who melded the team into a winner in the midst of racial tension. He was proud of helping Birmingham boost its self-esteem and showing how integration could work.

There was a special benefit for Birmingham. The horrors of 1963 were put on hold. As stated in the Birmingham News, “This team earned a special niche in local memory, chiefly that for three months they interrupted the clouds over Birmingham.”

On the baseball side, Birmingham continued for years to feed good players to the A’s. But that’s a story to save for a future Hot Stove.

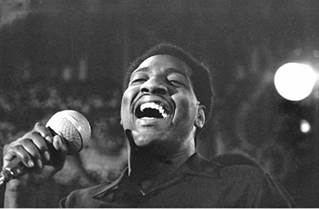

Lonnie’s Jukebox – Otis Redding: On March 1, 1964, Sam Cooke released a new album, Ain’t That Good News. The title of one of the tracks would have made a good slogan for the upcoming season for the Birmingham Barons: “A Change is Gonna Come.” Sam wrote the song, and I used his recording to finish my MLK message in 2018 (#66 at this link to prior MLK messages). This year I will end with a cover of Sam’s song by a singer who went to the same Macon high school as Blue Moon Odom – the great Otis Redding. Click here for his soulful version of the song that became a civil rights anthem.

MLK Day: Please join Rita and me in honoring Martin Luther King Jr. on Monday, January 20. Not literally joining us. We will be doing our toast to MLK on a beach in Cabo. Plus a second toast to the Barons of 1964.