As I hit “send” on this email, President Obama is attending a “Béisbol” game in Havana between the Tampa Bay Rays and the Cuban National Team. His guests include the wife (Rachel) and daughter (Sharon) of Jackie Robinson. Former Major Leaguer Luis Tiant threw out the ceremonial first pitch in this return to the stadium where he played when named Rookie of the Year in the Cuban League (1960-61).

Jackie Robinson was in Havana 69 years ago for spring training with the Brooklyn Dodgers. GM Branch Rickey had moved spring training from the Grapefruit League to Havana to provide a friendlier atmosphere for Jackie and two other future black all-stars, Don Newcombe and Roy Campanella.

A few days after Jackie and the Dodgers had arrived in Havana, the Cuban League was finishing what has been called its greatest pennant race of all time. The first baseman for the pennant winner was our own Buck O’Neil.

In that very same spring of 1947, the Cactus League was born in Arizona.

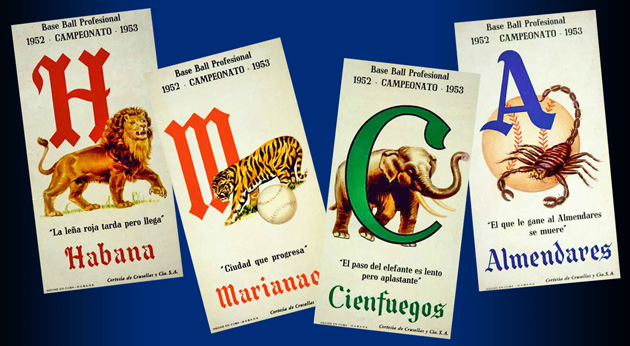

The Cuban League: The Cuban league is the longest and oldest professional baseball league outside the United States. It started in 1878 and ended by order of Fidel Castro in 1961. The league generally had three to five teams and was mostly centered in Havana. The quality of play was very good, and by 1959, 77 Cubans had gone on to play in the Major Leagues. At that time, there had only been one Dominican. Since then, there have been 640 Dominicans. Amateur baseball has continued at a high-skill level in Cuba, as evidenced by a line of excellent players who have been able to defect (e.g. Yoenis Cespedes, Yasiel Puig, Aroldis Chapman and Kendrys Morales).

The 19th century teams in Cuba excluded blacks, but after Cuban whites and blacks fought side-by-side in the Cuban War for Independence and the Spanish-American War, the teams relented and ended segregation in 1900. The effect of war was slower in the U.S. There were two World Wars before 2nd Lieutenant Jackie Robinson became the first black to play in the Major Leagues. But baseball was ahead of the military – the armed forces were not integrated until Harry Truman’s executive order in 1948. Of the 16 major league teams, 10 did not field a black player until after the end of the Korean War. By the time the Red Sox capitulated in 1959, the country was in the early stages of the Vietnam War.

The Cuban Baseball Mosaic: The difference in racial attitudes of the United States and Cuba created three levels of diversity in baseball for the first half of the 20th century:

1) The Cuban League. There was no segregation, so players were black, white and mixed and came from the U.S., Cuba and other Hispanic countries. The absence of segregation was also the case in other Caribbean Islands and Mexico, and some Major Leaguers also played in those countries.

2) The Major Leagues. The players were white, including (a few) white Cubans. Probably the most famous Cuban in this category was pitcher Dolf Luque who played in 20 major league seasons from 1914 to 1935 and got 194 wins. He was described as fair skinned and blue-eyed, but as was often the case with teams recruiting Cubans, the color line was flexible when it came to blood, but not skin color.

3) The Negro Leagues. With few exceptions, the players were black, including black Cubans and other Hispanics. There was a team in the Negro Leagues called the New York Cubans with both black and white Cubans on the roster.

The regular season for the Cuban League was played during the winter, and so the players could migrate between leagues to play baseball year-round. Many stars from the Negro Leagues played in Havana – Josh Gibson, Satchell Paige, Oscar Charleston and Cool Papa Bell. In anticipation of today’s game in Cuba, President Bob Kendrick of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum has been sending out tweets to commemorate the rich combined history of the Cuban League and the Negro Leagues. The two pieces of artwork shown below (Buck and Dihigo) were part of Bob’s tweets.

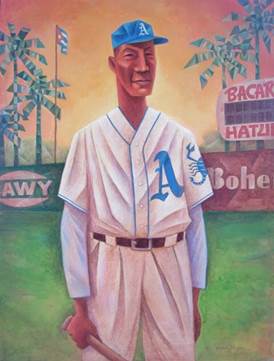

The Cuban Pennant Race of 1946-47: In the last month of the season, the Almendares Scorpions made up a 6-game deficit to the Habana Lions. With three games remaining at the end of the season, Almendares was behind by 1.5 games. They needed to win all three games to win the pennant, and they did so. The winning pitcher for Almendares in two of those games was Max Lanier, a white player from North Carolina who played with the St. Louis Cardinals from 1938 to 1946. Lanier had won the clinching game for the Cardinals in the 1944 World Series. The first baseman for Almendares was Buck O’Neil who played the 1946 regular season with the Kansas City Monarchs before heading to Cuba for the winter.

Buck said “One thing I liked about Cuba was the fact that you were a ballplayer and a Cuban was a Cuban, whether he was black, green, gray. Here I was a black American. But you were a Cuban regardless of what color you were and that really stuck with me.” This Ramon Olivera’s painting shows Buck in his Almendares Scorpions’ uniform with the team logo on his arm.

Buck O’Neil in Cuba

The Havana Sugar Kings: The Havana Sugar Kings, a Triple-A affiliate of the Cincinnati Reds, played in Havana from 1954 to 1960. Many of the players were Cuban, and the team became a showcase for Cubans moving up to the Major Leagues. The team played in the International League that included teams in the U.S. and Canada. In 1959, the team won the Little World Series played by the top Triple-A teams. With the changes going on after Castro took over in 1959, the team became a victim of the Cold War between the U.S. and Cuba. Reacting to Cuban nationalization of U.S.-owned businesses, the Eisenhower administration pressured Commissioner Ford Frick to relocate the team in midseason – the Sugar Kings became the New Jersey Jerseys in July of 1960. Frick also banned any major leaguers from playing winter ball in Cuba. Castro then banned Cubans from playing in the U.S. – that is why defectors are now the only Cubans playing U.S. baseball.

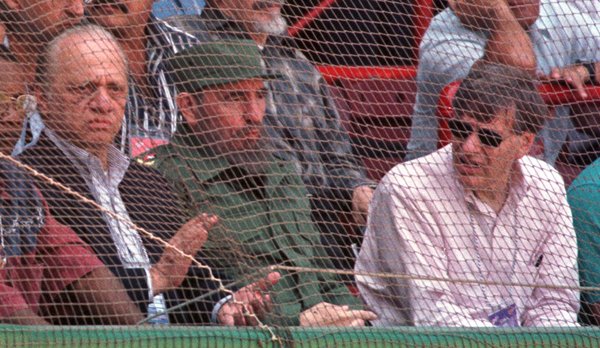

MLB in Cuba in 1999: Between 1959 and today, there has been only one MLB game played in Cuba. Peter Angelos took his Baltimore Orioles to Havana to play a Cuban team on March 28, 1999. A good story was in the NYT yesterday for those wanting more detail (click here). Below is a photo of Angelos, Fidel Castro and Commissioner Bud Selig at that game.

Cubans in the Hall of Fame: Only one Cuban has been voted into the Hall of Fame by the baseball writers: Tony Perez, the slugging first baseman for the Big Red Machine in Cincinnati. Perez was one of the last Cubans to legally come to the U.S. before Castro closed the door. Although not in the Hall of Fame, several other Cubans have been stars in the big leagues, including Luis Tiant, Tony Oliva, Mike Cuellar, Minnie Minoso, Rafael Palmeiro, Bert Campaneris, Jose Canseco and Camilo Pascual.

Three Cubans have entered the Hall of Fame through Negro Leagues balloting: Martin Dihigo, Jose Mendez and Cristobal Torriente (the “Babe Ruth of Cuba”). Dihigo is considered one of the biggest stars of the Cuban, Mexican and Negro Leagues – he is in the Hall of Fame of each country. He was a very successful pitcher and batter, playing year-round in the various leagues. In Cuba, he was called “The Immortal” and in Mexico, “El Maestro.” Below is a Gypsy Oak piece of baseball art featuring Dihigo:

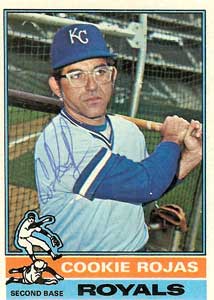

The Kansas City Royals and Cuba: One of the most popular players in a Royals uniform was Cookie Rojas who played 2nd base and was a four-time all-star for the Royals from 1970 to 1977. Cookie was born in Havana and signed up at age 17 with the Cincinnati Reds, the parent team for the Havana Sugar Kings. Cookie played for the Sugar Kings in 1959 and 1960 and relocated with the team to New Jersey in mid-1960. He went on to play 16 years in the Major Leagues.

The story of Kendrys Morales is a study in persistence. Morales played on the Cuban national team, but was banned from Cuban baseball in 2004. It was believed that he had talked with an agent and was attempting to flee to play in the U.S. He has denied that he talked with an agent, but he was left with little choice but to try to defect after he was banned. He tried to leave many times and occasionally was jailed. On his 13th attempt, he reached Florida. As was common for Cuban defectors, he did not first establish U.S. residency as that would subject him to the MLB draft rather than being a free agent. He instead defected to the Dominican Republic where he played for a Dominican team while being scouted by major league teams. After playing eight years in the majors, he signed as a free agent with Kansas City for 2015 and 2016. As we Royals fans know, the signing turned out to be golden (or maybe call it silver since he won the Silver Slugger Award as the best DH in baseball for 2015).

The Cactus League: Florida’s resistance to integration played at least a partial role in starting the movement of teams to Arizona for what became known as the Cactus League. When Bill Veeck owned the minor league Milwaukee Brewers, the team trained in Ocala, Florida. Veeck was sitting in the Jim Crow section with black fans when the sheriff told him to leave. Veeck said he was not bothering the black fans and he was having a nice talk with them. Veeck’s refusal to move also brought the mayor over to add support to the sheriff. This incident did not sit well with Veeck, and when he later owned the Cleveland Indians, he chose to head to Tucson in 1947. Race relations were indeed better in Arizona, but not perfect – no Jim Crow bleachers, but still hotel issues. Veeck was also thinking ahead – he signed Larry Doby in July of 1947 and Doby became the first black player in the AL.

Veeck had at least two other incentives: (i) he owned a ranch near Tucson and (ii) teams would not lose playing time as much as in rainy Florida. He also had another owner to join him in Arizona – Horace Stoneham of the New York Giants opened camp in Phoenix. Five years later, the Cubs moved from their long-time camp in Catalina to Mesa. With some help from baseball expansion, the Cactus league grew to eight teams by the 1980’s. But the future of the league was threatened as Florida cities went on a building spree with new stadiums. Each Florida city that lost a team was a potential suitor for an Arizona team. Arizona’s solution was to funnel money to the teams via a car rental tax mostly paid by tourists (as was done in KC to pay for the Sprint Center).

The stakes got even higher as 2000 approached. Las Vegas was eyeing Florida teams and prompted the Florida legislature and Governor Jeb Bush to add new incentives. Arizona then added major incentives for both baseball and football stadiums, forming the Arizona Sports and Tourism Authority, funded (naturally) by tourists with a hotel tax and more tax on rental cars. The building boom was on. The incentive battles between cities and states continue to this day, much like the economic development incentive fights in the Border War between Kanas and Missouri. Each league currently has 15 teams but there are, no doubt, some teams in play for the next move to a shiny new stadium.

Kansas City and Spring Training: When the A’s moved from Philadelphia to KC in 1955, they continued to hold spring training in West Palm Beach until 1962. They moved to Bradenton in 1963, but after 1967, Kansas City fans lost interest in the A’s. Charlie Finley kept his now-Oakland A’s in Bradenton in 1968, but then moved the team to Arizona to be closer to the team’s new fans.

The expansion Kansas City Royals chose Fort Myers in their first year of 1969 and trained there until 1987. In 1985, assistant GM John Schuerholz attempted to get the city to pay for some upgrades to the facilities, a cost of about $300,000. The city balked, saying that “People don’t come to Fort Myers for baseball. They come for shelling and golfing.” The city had no issue with the Royals moving to another city, even after the Royals won the 1985 World Series. It did not take long for the city to regret this, voting out the commissioners who made the decision, and then paying millions to bring in the Twins in 1991. They later made another large investment to bring in the Boston Red Sox in 1993.

The Royals became part of an ambitious venture called Baseball and Boardwalk where they trained from 1988 to 2002. Next door was a baseball-themed amusement park, and the developer’s idea was to provide a dual draw for family tourism. The amusement park quickly failed and was closed in 1990, leaving the Royals in a fine stadium, but with a dormant neighbor. Later, as had become the baseball custom, the Royals were courted by Arizona. The city of Surprise had built a two-team complex at a cost of $48 million, to be used by any teams willing to move from Florida. Texas and Kansas City said yes and both began operations in 2003. This past year, the city agreed to spend another $22 million to upgrade the facilities in return for a lease extension to 2030.

Cactus League 2016: Rita and I leave in the morning for Phoenix to take in four Royals games in the Cactus League. Report to follow.

Go Royals!

Viva la Béisbol!