Ken Hill: From Pendergast to Carnahan (Part One of Three)

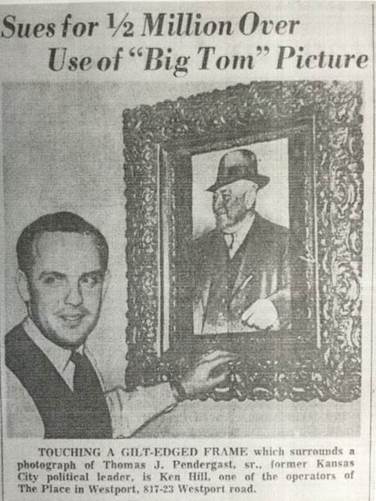

My first encounter with Ken Hill was in 1966 and came through Tom Pendergast, the political boss who helped Harry Truman become a County Judge and U.S. Senator. I was in law school at UMKC, and my classmate Hollis Hanover took me to a saloon on Westport Road operated by his friend from college – Ken Hill. In July of 1965, Ken had opened a bar at the back of a larger venue known as The Place. He called it “Big Tom’s,” and the speakeasy atmosphere was accented by old photos of famous Kansas Citians, including Truman, William Rockhill Nelson and Tom Pendergast (hence, Big Tom’s). By the time I first saw the bar, it was no longer called Big Tom’s, nor was there a photo of Pendergast. Litigation had intervened.

Tom Pendergast died in 1945, but his son sued Ken for $500,000 for invasion of privacy, specifically for associating the Pendergast name with “unlawful scandalous and criminal activities through the innuendo of interior design…by extolling the consumption of intoxicating liquor and ridiculing abstinence.” Ken agreed that he was trying to capture the nostalgia of the 1930’s and thought he was doing so in a positive way by showcasing some of the colorful characters from Kansas City history. Ken preferred to get on with business and stop paying legal fees, and so he settled the case by removing the photo and changing the name. The lawsuit publicity was good for business, and new patrons like me were shown the outline on the wall where the framed photo of Pendergast had once hung. It was still Big Tom’s, just sub rosa.

My Google search on the lawsuit led me to the Pendergast archives at the UMKC branch of the State Historical Society. I was surprised to find that there was a second lawsuit that claimed Ken was not abiding by the original judgment, and the file included a copy of Ken’s deposition testimony. Even though Ken had changed the name to “The Big Deal,” there was evidence that customers were still using the original name, including in a flyer for a scavenger hunt that ended at the bar. It also did not help that Ken had overlooked changing his white and yellow page listings. The suit was settled for $500. He testified he was planning to change the name to “Ken’s Place” with the hope that customers would take to that name and keep him out of court.

I will always remember it as Big Tom’s – I did not even remember the other two names until I read Ken’s deposition. Today, you can get a feel for Big Tom’s by having a drink at “Tom’s Town” where a big framed photo of Big Tom is prominently displayed. Unlike Ken, the owners of Tom’s Town acquired the necessary right to the names for their speakeasy and liquor (selections from their distillery include “Pendergast’s Royal Gold Bourbon” and “McElroy’s Gin”). Henry McElroy was the city manager for much of the Pendergast era. Tom’s Town is at 1701 Main in the Crossroads District, about 2 blocks from the old Pendergast headquarters at 1908 Main.

The Early Political Years: The surprise gem for me in Ken’s deposition testimony was a description of his early political days. They included the campaigns of Larry Gepford/Prosecutor (1962), Tom Gavin/City Council (1963), Jim Trimble/Attorney General (1964) and the Committee for County Progress (1966). Hollis Hanover tells me that Ken and others formed a political club in 1960 (City Central Political Committee, the CCPC) and worked on a magistrate judge race. Hollis also says that Ken’s political leanings were not clear at that young age, but Ken found that if you wanted to be meaningfully involved in local or state politics in the early 60’s, you were a Democrat. You know, the good old days.

In Ken’s first campaigns, he mostly worked for candidates who were backed by the Jackson Democratic Club, an heir to the old Pendergast organization. After Tom Pendergast went to jail in 1939, the rival Citizens Association had swept out the Pendergast machine from city hall at the next election. But clubs and factions allied through old Pendergast ties continued to have influence in county and state offices and on occasion would elect a city councilman. This meant that the factions still controlled the patronage jobs at the courthouse, and Ken Hill had one for a period of time – an assistant constable (process server).

In 1955, mayoral candidate H. Roe Bartle declined support from both the Citizens and the factions so he could be independent. Bartle won, and was reelected in 1959, this time with the tacit support of the factions. The factions also won several council seats. The Citizens roared back in 1963 to elect Ike Davis as mayor and throw out all but one of the faction councilmen (Sal Capra). One of the losing faction councilman was Tom Gavin whose campaign manager was 26-year old Ken Hill.

Tom Gavin and Ken Hill: I never knew Tom Gavin, but I know he was special to Ken. The Gavin story I remember was that Ken would often drive Gavin to meet with Harry Truman at the Truman Library. This was how Ken got to know Truman. As I worked on this post, I did a little research and found that Gavin was quite a character in Kansas City history. In the 1920’s, he joined Tom Pendergast’s Jackson Democratic Club and worked under ward leader Tom Evans. In an oral history at the Truman Library, Evans said that Gavin ran a speakeasy during Prohibition and “also ran a gambling joint when Kansas City was wide open.” Gavin befriended and worked for Harry Truman who had been elected as County Judge for the 3-person administrative court that ran the Jackson County. After service in World War Two, Gavin won election to the city council and would remain there until 1963.

Gavin’s friendship with Truman continued during and after Truman’s Washington years as Senator, Vice President and President. From an article in the Chicago Tribune in December of 1951: “President Truman today led reporters on a 10 mile Keystone Kops comedy chase through stop lights and railroad warning signals to spend the day with his old cronies at the Hotel Muehlebach.” Of the 20 or so “cronies” named in the article, Tom Gavin was first on the list.

Gavin gained national attention in 1952 when he was designated by Truman to be Truman’s alternate at the 1952 Democratic Convention in Chicago. Truman’s choice for his successor as President was a well-guarded secret, and only Gavin knew who he was to vote for. This would then be the signal to others in the hall on Truman’s preference. The national press described Gavin as a chubby city councilman and brewery executive (he was a VP at Muehlebach Brewery). From the oral history of Randall Jessee at the Truman Library: “There was tremendous interest in Tom Gavin that year, who was the President’s alternate. There was a great TV coincidence on this, because at the same instant that Tom Gavin was rising on the convention floor to cast his vote, President Truman was getting on the plane in Washington to come to the convention, and they were able to superimpose these two pictures, which by pure coincidence happened at the same instant.” Truman’s vote was for Adlai Stevenson.

His relationship with Truman put Gavin “in the room” with three other presidents. In 1961, Truman took Gavin along to a DC fund raiser and got this signed photo from Truman (Gavin, Truman, Sen. Fulbright and President Kennedy):

In November of 1963, eight months after Ken Hill had run Gavin’s campaign, President Kennedy was assassinated. Truman asked Gavin to accompany him to the funeral, and they stayed at Blair House. There is an entry in Lyndon Johnson’s “Daily Diary (Worksheet)” showing that at 4:57 on November 23, 1963, LBJ had a “meeting w/ President Truman…Tom Gavin of Kansas City, Ed Pauley of Los Angeles, John Snyder joined in the Truman interview.” At the funeral, Truman and his daughter Margaret sat with Ike and Mamie Eisenhower who then joined them at Blair House for a visit – later touted by many historians as the reconciliation of Truman and Ike. As explained by Gavin who was there (and recounted in Brian Burnes Harry S Truman: His Life and Times), Truman and Ike shared sandwiches and small talk, and at one point Ike moved his chair closer to Truman. Gavin said “It was just two old soldiers recalling the times and people they had known…It was two men who had lived in the same time remembering things they cared about.”

I can only imagine the rich history that Ken Hill must have heard from Tom Gavin. In addition to their time together on the drives to the Truman Library and in the 1963 campaign, Gavin was a regular at Big Tom’s which became a hangout for politicos in the city. In Ken’s deposition, he said that before he opened the bar, he met with a group of friends, including Gavin, to come up with ideas for a name for the bar. Ken even joked in his deposition that he should have just said the bar was named after Tom Gavin. In a perfect touch of a mentor helping a protégé, Ken said Gavin bought the first drink on Big Tom’s opening day, July 12, 1965. Jerry Wyatt, a long-time friend and political ally of Ken on many campaigns, says that Gavin’s bourbon of choice was Old 1889, the brand he drank with Harry Truman.

1966 and 1968 – Charles Curry/Bill Morris: The year after opening Big Tom’s, Ken got involved in a major campaign that changed the face of Jackson County politics. The factions that grew out of the old Pendergast organization and various allies were in control of the county offices and the patronage that went with that. In a first step to change this, civic leader and business man Charles Curry won the race for Presiding Judge in 1962. Curry made a small advance in 1964 when his candidate Charles Wheeler became coroner. In early 1966, Curry formed the Committee for County Progress and recruited strong candidates for the nine county offices to be contested. A key aide to Curry was lawyer Charlie Hart who recruited Ken Hill to the CCP cause. Charlie and Ken each had a circle of friends active in politics and they had all worked together on the 1962 Gepford campaign.

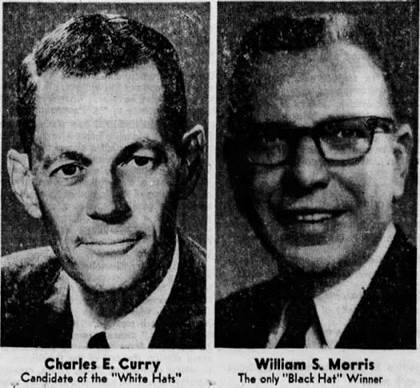

Curry put together quite a campaign. He brought in consultant Matt Reese who had made his mark on the 1960 JFK campaign. He and other CCP founders raised ample funds. The Kansas City Star strongly supported the effort and was instrumental in making it a campaign of the “White Hats” against the “Black Hats.” Ken, Charlie Hart and their friends put together a campaign organization that covered a good part of western Jackson County. The CCP won eight of the nine county races. The only miss was on Public Administrator which was won by incumbent Bill Morris. Some of the winners were George Lehr/Collector, Bruce Watkins/Circuit Clerk, Joe Teasdale/Prosecutor and Charlie Wheeler/Western Judge – all to later become candidates for higher office. The twist for Ken and Charlie was that Teasdale beat Larry Gepford who they had worked for in 1962.

The battle of the CCP and the factions even gained attention in St. Louis. This dual photo from the Post-Dispatch was a pretty good summary:

So what did Ken do after his successful venture with Curry and the CCP? He joined the 1968 campaign of Bill Morris for Lt. Governor. Morris had become politically powerful as an ally of Governor Warren Hearnes who gave Morris a major say on state patronage in Kansas City. Ken’s long-time friend Jim Cleary tells me that Larry Gepford recommended that Morris hire Ken who had proven to be an industrious campaign worker and had statewide experience from the 1964 Trimble campaign. Ken came on as the statewide campaign manager and made Cleary his campaign youth director. Morris beat Ed Dowd in the primary and went on to win the general. As in 1966, Morris won without the support of the CCP.

Gray Hats – 1970 and 1972: After the Morris campaign, Ken went to Florida for a business venture and mostly was outside the political scene for the 1970 and 1972 campaigns. Some of the CCP winners faced off against each other in 1970. New alliances were born and this blurred the lines between the CCP and the factions, some of which aligned as the “Regular Democrats.” Freedom Inc. had become a major player in the black community. In 1970, both the CCP and the Regular Democrats supported George Lehr to succeed Charles Curry as Presiding Judge and Harry Wiggins to succeed Charles Wheeler as Western Judge. Their opponents were Charlie Wheeler (moving up to the Presiding Judge race) and Joe Teasdale, both supported by the CCP in prior elections. Wheeler and Teasdale lost, but Wheeler went on to become Mayor of Kansas City in 1971 and Teasdale was elected Governor in 1976.

To again prove the adage that politics makes strange bedfellows, the CCP in 1972 surprisingly backed Bill Morris in his primary race for Governor against Ed Dowd and Joe Teasdale. The two KC candidates lost to Dowd of St. Louis, but the landslide that overtook McGovern trickled far down the ticket. In the general, Nixon won the state by about 400,000 votes, Kit Bond beat Dowd by 200,000 votes, and Jack Schramm, a very popular CCP candidate, lost the Lt. Governor’s race by 8,923 votes. You rarely see ticket splitting of that magnitude these days.

As it would turn out for Ken and me, there was a bright spot in that 1972 landslide. The first elections under the new county charter were held and 15 first-time county legislators were elected. My law school friend Mike White won the third district seat, and he won it in dramatic form. After a recount of the absentee ballots, the final tally was White – 14,071 and Kartsonis – 14,070. That one-vote victory started a chain of events that Ken nor I could anticipate at the time.