This post is not about the end of the MLB lockout. Anything I write would be eclipsed within a day by news of free agent signings, spring training news, roster moves, Bobby Witt Jr. hitting a homer, etc. A whole winter’s worth of baseball coverage is being compressed into the relatively few days before the season opens on April 7. I can’t keep up. Royals pundit Rany Jazayerli captured this in a clever tweet and photo:

“Baseball news the last three months. Baseball news the next three days.”

Instead, I’m going with some baseball nostalgia in honor of St. Patrick’s Day. I’m getting excellent help from my friend Pat O’Neill who has penned a story about baseball-playing Irish politicians named Pendergast. Big Jim at first base, Boss Tom at third and Jesse James Jr. in center field. In 1898.

Pat’s expertise on the local Irish clans is best evidenced by his 2015 book, From the Bottom Up: The Story of the Irish in Kansas City. Pat is a storyteller, or as he wrote when he signed my copy of his book, “If I had not grown up to be a teller of tales, I’d have been a lawyer – but never one as good as you!” I believe they call that last part blarney.

The O’Neill family has long been involved with Kanas City’s St. Patrick’s Day parade, which will be held this year after a two-year Covid hiatus. The inaugural parade in 1974 was the brainchild of public relations guy Pat O’Neill Sr. (Pat’s dad) and radio personality Mike Murphy. The two promised the “world’s shortest and worst parade.” It was indeed short – one block on Baltimore from the Continental Hotel to Dan Hogerty’s saloon. But it could not have been the worst since it has grown to be one of the biggest St. Pat’s celebrations in the country.

Below, from that first parade in 1974, Dan Hogerty is wearing the “Parade” sandwich board (the back said “End of Parade”). Pat O’Neill Sr. is marching just behind Hogerty’s right shoulder.

Pat followed in his father’s footsteps, both in the parade and in the PR and promotions business. Pat retired in 2018, leaving the business in the good hands of his daughter Keli. He remains on the company website as “Founder and Bartender” and this description of his career: “[Pat] earned his stripes, reputation, gray hair and wrinkles as a consultant, publicist and media spokesperson for entertainment venues, casinos, religious organizations and important civic issues in Kansas City and throughout the region, before retiring in 2018 and taking over coffee-fetching and bartending duties.”

In emails, Pat signs off as “Out to Pasture – Retired.” As you will see below, Pat may be out to pasture, but he is still telling tales.

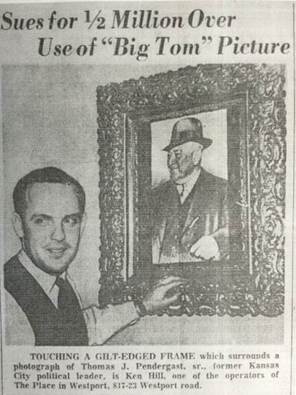

Ken Hill and Big Tom (Pendergast): Before getting to Pat’s piece, I’m giving a shout-out to another person who told Pendergast tales, my good friend Ken Hill (RIP). In 2016, I chronicled Ken’s three decades in politics in a series of posts titled “Ken Hill – From Pendergast to Carnahan” (click here for the full series). The Pendergast portion of the series started with this Kansas City Star photo of Ken and “Big Tom.”

I met Ken in 1966 when I was in law school at UMKC. My classmate Hollis Hanover took me to a saloon on Westport Road operated by his friend from college – Ken Hill. Ken had opened the bar in 1965 at the back of a larger venue known as The Place. He called it “Big Tom’s,” and the speakeasy atmosphere was accented by old photos of famous Kansas Citians, including Harry Truman, William Rockhill Nelson and Tom Pendergast (hence, Big Tom’s). By the time I saw the bar, it was no longer called Big Tom’s, nor was there a photo of Pendergast. Litigation had intervened.

Tom Pendergast died in 1945, but his son sued Ken for $500,000 for invasion of privacy, specifically for associating the Pendergast name with “unlawful scandalous and criminal activities through the innuendo of interior design…by extolling the consumption of intoxicating liquor and ridiculing abstinence.” Oh my. Ken agreed that he was trying to capture the nostalgia of the 1930s and thought he was doing so in a positive way by showcasing some of the colorful characters from Kansas City history. Ken preferred to get on with business and stop paying legal fees, and so he settled the case by removing the photo and changing the name. The lawsuit publicity was good for business, and new patrons like me were shown the faded outline on the wall where the framed photo of Pendergast had once hung. It was still Big Tom’s, just sub rosa.

Ken’s interest in Pendergast was no doubt enhanced by Ken’s early political mentor, Tom Gavin, who was quite a character in Kansas City history. In the 1920s, Gavin joined Tom Pendergast’s Jackson Democratic Club and worked under ward leader Tom Evans. In an oral history at the Truman Library, Evans said that Gavin ran a speakeasy during Prohibition and “also ran a gambling joint when Kansas City was wide open.”

Gavin befriended and worked for Harry Truman who was elected as a Jackson County administrative judge with Pendergast support. Gavin was often seen with Truman during and after the presidency, and the national press described him as “the quiet little Irishman from K.C.” Below, at a 1961 DC fund raiser: Gavin, Truman, Sen. Fulbright and President Kennedy.

When Ken became involved in politics in the early 1960s, he met Gavin who was then a KC city councilman. They became friends, and Ken often drove Gavin to meet with Harry Truman at the Truman Library. When Gavin ran for reelection in 1963, 26-year-old Ken Hill was his campaign manager. It was not a good year for the old-line factions, and the Citizens Association candidate defeated Gavin.

Gavin was a regular at Big Tom’s which became a hangout for politicos in the city. Ken said that before he opened the bar, he met with a group of friends, including Gavin, to come up with ideas for a name for the bar. After the “Big Tom’s” lawsuit, Ken joked that he should have just said the bar was named after Tom Gavin. In a perfect touch of a mentor helping a protégé, Gavin bought the first drink on Big Tom’s opening day, July 12, 1965. Jerry Wyatt, a long-time friend and political ally of Ken on many campaigns, says that Gavin’s bourbon of choice was Old 1889, the brand he drank with Harry Truman.

Tom’s Town: Today, you can get a feel for Big Tom’s by having a drink at “Tom’s Town” where a big framed photo of Big Tom is prominently displayed. Unlike Ken Hill, the owners of Tom’s Town acquired the necessary rights to the names for their speakeasy and liquor (selections from their distillery include “Pendergast’s Royal Gold Bourbon” and “McElroy’s Gin”). Henry McElroy was the city manager for much of the Pendergast era.

Tom’s Town is in the Crossroads District at 1701 Main, about 2 blocks from the old Pendergast headquarters at 1908 Main. When asked how he justified ignoring Prohibition, Tom Pendergast quipped, “The people are thirsty.” They still are.

Pat O’Neill On Baseball and the Irish: Last year, Pat and his co-author Tom Coffman published Ted Sullivan, Barnacle of Baseball (2021). It’s about an Irishman (surprise) who was a major early influence on the game of baseball (see info on the book here). Al Spink, writing in the Sporting News in 1909: “[Sullivan’s] travel and brisk acquaintance have added to his natural fund of Irish wit and made him delightful as a raconteur. No man in the baseball world can compare with Sullivan as a storyteller.” Sounds like Pat O’Neill. Must be something in the Irish water. Maybe bourbon.

When Pat signed my copy of the book, he wrote “To the Shalton Clan: Love livin’ on the Hot Stove!” His co-author Tom Coffman added “Where things are always sizzling!” More blarney, but I like it.

And now Pat really is livin’ (writin’) on the Hot Stove. I’m sure you will enjoy his take on the Pendergasts and baseball.

THE PENDERGASTS PLAYED HARDBALL

Their 1898 Court House Baseball Team Featured Big Jim at First Base, Boss Tom at Third Base, and Jesse James in Center Field

In addition to organizing many teams of his own, Jim Pendergast once played for “Burrows’ Bats,” a team formed by his Republican rival on the city council, Tenth Ward Alderman and Speaker of the Lower House, A.D. Burrows.

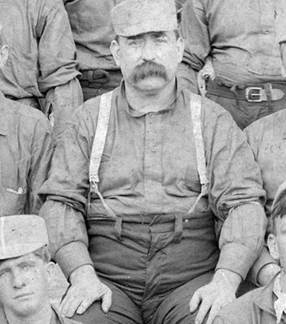

As much as they loved settling political scores at the voting booth, the Pendergast brothers, Jim, Mike and Tom, loved playing and winning baseball games. The family patriarch — the affable and benevolent “Big Jim” Pendergast — especially loved the game, and often staged contests to build teamwork among his followers at the Jackson County courthouse and his fellow aldermen at city hall.

In addition to sponsoring and playing on amateur baseball teams in the late 1800s and first decade of the 1900s, “Big Jim” organized annual contests with his counterparts across the river in Kansas. Thousands of tickets were sold, and the build-up to those contests typically included lots of boasting and joking and pre-game pageantry. The money raised would be given to local charities on both sides of the state line.

The hefty alderman with the walrus mustache always served as captain of his teams, and staked his claim to first base. On October 2, 1896, he paraded his city hall squad, outfitted in black, bloomer-style-trousers, yellow shirts and white skull caps, to old Exposition Park at 15th and Montgall, behind a marching band and the two cities’ mayors waving from a plumed and bannered carriage.

From the Kansas City Journal of October 3, 1896, under the headline “ALDERMEN IN BLOOMERS”:

“In the great aldermanic ball game yesterday the fathers of Kansas City, Mo., triumphed over the patriarchs of the city across the Kaw. The wearers of the scarlet, who issued the challenge for the contest, and who marched proudly upon the diamond at 3 o’clock, straggled dismally off at 5, crestfallen, weary, and sorry they spoke.

“Those garbed in old gold and black are triumphant. They covered themselves in glory. They demonstrated that they can play ball, and that they are as well posted on the ritual of the game as on the methods of confirming a sidewalk contract under suspension of rules. Among the best players were Pendergast and Smith.”

The proceeds of the game benefited the Day Nursery of Kansas City, Mo., and the Rescue Home of Kansas City, Kan.

Court House Cronies vs. City Hall Gang

In June of 1897, brother Mike Pendergast filled in for Big Jim at first base, and the-then-young Tom Pendergast was listed as a substitute when the powers-that-be from the Jackson County courthouse took on the few surviving Democrats from City Hall.

Later that same summer, the Pendergasts switched sides. On August 7, the Kansas City Journal announced that, “Alderman Pendergast is manager of a club of baseball-playing city fathers, who are anxious to wipe up the Exposition ball park with the municipal lawmakers of Westport.”

The same edition of the paper also touted an upcoming contest with “Two clubs of Indians from the territory” and another to be played between Kansas City’s police and fire departments. Apparently, the fire department was unable to pump many runs across the plate in their matchup with the police, as Pendergast’s courthouse contingent soon announced that it was “very anxious to arrange a game with the nine of the policemen who wiped up the ground with the firemen a few days ago.”

Noted the Journal on July 13, 1898:

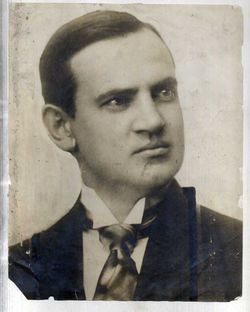

“If there is one place in the entire city where baseball fans are more rampant than at any other, it is in the county courthouse. Just at present the entire court house is enthused over its baseball team, which, it is said, can more than hold its own with any amateur nine in the city. The court house nine lines up as follows: Jim Pendergast, first base; Leahy, second base; Tom Pendergast, third base; Mike Casey, shortstop, Tom Sims, left field, Jesse James, center field, Frank Kelly, right field, Roberts, pitcher; Wofford, catcher.

That center fielder for the courthouse gang in their contest with the guardians of Kansas City’s peace was none other than Jesse Edwards James, the likable and well thought of purveyor of cigars in the courthouse lobby. Ironically, the “son of the famous bandit king,” as the Journal called him, would be charged just three months later with being part of a gang that in September had attempted to rob a Missouri Pacific train outside of Leeds.

An avid ball player, Jesse James, Jr. was popular among county and city officials – even after he was accused of robbing a train like his infamous father.

Many a business and civic leader came out in support of the 23-year-old Jesse, who had earned a reputation around town as an honest, hard-working fellow who couldn’t possibly commit such a crime. Even his grandmother, Zerelda Samuels, mother of Jesse Sr. (escorted into court by her other son, the “reformed citizen,” Frank James) took the stand in his defense. Jesse Jr. was eventually acquitted of charges that he had robbed the train, and went on to law school, became a defense lawyer, and played amateur baseball for the Bruce Lumber Company team in Kansas City.

1899: Bureaucrats Cross Bats for Big Convention

“A real game of ball” was promised the citizens of KCMO AND KCK in the summer 1899. Once again, the diamond master of the Kansas City squad was Alderman Jim Pendergast. He issued the challenge, selected the black and red uniforms, assigned positions, and egged the papers for publicity.

From the August 9, 1899 edition of the Kansas City Journal:

“To show just what the Kansas City men can do it may be stated that yesterday afternoon while Jesse L. Jewell (Republican alderman from the 3rd Ward) and James Pendergast were engaging in a little practice, Mr. Pendergast, at the third throw, apparently without more than ordinary effort, threw a new ball through a $1.50 pane of glass. Extreme modesty on Mr. Pendergast’s part induced him to attribute the success of the throw to Mr. Jewell, who was supposed to have stopped the ball, but the latter insisted that Mr. Pendergast was entitled to all the honors and he finally accepted them, and paid for the broken window.”

The Journal reporter, with his usually sharp tongue firmly in cheek, wrote: “Mr. Pendergast also borrowed a number of gloves for the use of the pitchers, catchers and baseman, but owing to unfamiliarity with the implements used in the national game, he got boxing gloves and was not advised of his mistake until Jesse Jewell, who attended a baseball game at Harlem in 1879, and in consequence knows all about it, told him the difference.”

More hype followed leading up to the “real game of ball.” Six thousand tickets were printed and sold for 25 cents each. The proceeds from the contest between the two cities’ elected officials were to benefit Kansas City, Missouri’s, effort to attract the 1900 National Democratic Convention.

On game day, KCMO’s lineup included Big Jim at first base; Police Chief John Hayes as umpire, and Sgt. John Thomas as “official bearer of the water can”

“SUNFLOWER WILTED” was the Journal’s headline the next day.

“Kansas City, Kan., team goes down to glorious defeat,” was the news. The councilmen from Missouri had prevailed by a score of 34 to 33, leaving “big chunks of gloom to be shoveled out of KCK city hall by the janitor on Monday.”

Gushed the Journal: “The credit for this glorious victory belongs to all Missouri players, but especially to Captain Pendergast… Pendergast was first to bat and wanted to use a tennis club to hit the ball, but the Kansans wouldn’t stand for it. But he got even by slamming a three bagger to right field and scored on a bunt.”

Seems the gregarious, hard-throwing alderman couldn’t break any more windows, however, for it was reported that, “in vain did Captain Pendergast essay to pitch… the Kansas team simply kept the ball up in the air all the time with Pendergast trying to get it across the plate.”

As Alderman Jim grew older, and his younger brothers Tom and Mike grew ever busier counting votes and running their saloons, the Pendergasts were content to put their bats back in the rack and annually sponsor an amateur baseball team called, simply, “The J. Pendergasts.”

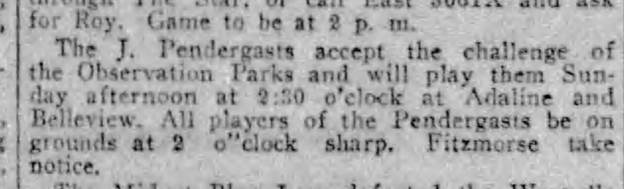

A classified ad in the Kansas City Star, May 5, 1907

Pat O’Neill

Readers, note I have included Pat as a CC to this post. So if you’d like to comment to him on his piece, just “Reply All” to this email.

Standing With Ukraine: Congress just passed a funding bill that allocates substantial funds to aid Ukraine in its fight against the Russian invasion. Seventy five years ago (March 12, 1947), President Harry Truman addressed a joint session of Congress asking for funds to protect against a communist takeover of Greece and Turkey (the “Truman Doctrine”). HST: “It must be the policy of the United States to support free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures. I believe that we must assist free peoples to work out their own destinies in their own way.”

In 1949, under Truman’s leadership, the United States became a founding member of NATO.

The county judge from Pendergast did good.