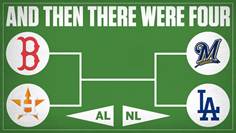

How about those Milwaukee Royals (a/k/a Brewers)? Lorenzo Cain knocked in the winning run in the tiebreaker to win the NL Central. In Game 1 of the NLDS, Mike Moustakas stroked a hit for the walk-off win in the 10th inning (below, #6 Cain celebrates with Moose). In Game 2, Moose doubled and scored the first run, and then he and Erik Kratz knocked in the other three runs in a 4-0 win. Kratz was a backup catcher for the Royals in 2014 and 2015, but never made it into a postseason game. Kratz continued his success In Game 3, getting three more hits to finish with an NLDS average of .625. Kratz is the oldest player (38) to make his postseason debut since 1905. Joakim Soria had a 0.00 ERA in three relief appearances. The Brewers easily swept the Rockies – Rocktober is over and out.

Milwaukee is also on a winning streak similar to the Royals of 2014. The Royals won the last regular season game, then the Wild Card and then swept both the ALDS and ALCS, a total of nine straight games. Milwaukee won their last seven games of the regular season, then the tie-breaker and now three in the NLDS, a total of eleven straight (and counting).

The other NLDS pairing also featured a Royals alumnus. Ryan Madson won a couple of games in the postseason for the 2015 Royals. The 38-year-old pitcher started the season with the Nationals and came to the Dodgers five weeks ago on the waiver deadline. In Game 4 of the NLDS against the Braves, Madson entered the game in the bottom of the 5th with the bases loaded and one out. All runners were stranded as Madson got two pop-up outs. The Dodgers took the lead in the next inning and Madson was credited with the win as the Dodgers finished off the Braves in the NLDS, three games to one.

In the American League, I had two primary hopes: (i) Cleveland would break its 70-year World Series drought, and (ii) the Yankees would not be in the Series. Cleveland was quickly dispatched in a Houston sweep. So I am left celebrating in the negative. With apologies to Hot Stove readers/Yankee fans Gary Barnett and Jay Anderson, I enjoyed watching Boston eliminate the Yankees. So did fellow law firm retiree Tommy Taylor who emailed me as the game ended, “At least the Yankees lost!! I can now enjoy the rest of the season.” My personal highlight: Boston’s Brock Holt hit for the first-ever cycle in postseason history.

The ALCS should be a barn burner, matching two 100+ teams: Boston (108 wins) and Houston (103 wins). I don’t have a favorite there, but I am rooting for the Brewers over the Dodgers in the NLCS. And not just because of the Royals expats. The franchise has never won the World Series. It’s time.

2018 – Home Runs, Strikeouts and Walks: Attendance in baseball was down this season. Some blame the length of the games which in turn are full of plays that only involve three players: the batter, pitcher and catcher. With batters swinging for the fences, they strike out a lot. The pitchers are more careful as they try to avoid home runs, so they walk more. If the batter does not hit a home run, he lines it to an infielder who has shifted to the right place based on analytics. So there are less singles. Less people on base to steal bases. Less reason to steal if you do get on – just wait for the homer to bring you in. And so on.

So the powers that be are contemplating rules changes. If this happens, it won’t be the first time that the rules have been tweaked to satisfy the fans. Let’s take a look at what happened 50 and 100 years ago.

1918 – Beginning of the End of the Dead-Ball Era: The season of 1918 was not good for baseball attendance. Much of that related to the war, but the owners found that fans were also tiring of the lack of offense. A good indicator of pitching dominance was the scoring in the World Series of 1918. The Red Sox won four games: 1-0, 2-1, 3-2 and 2-1. The Cubs won twice: 3-1 and 3-0. There were no home runs.

So in 1919, the baseball establishment started looking for ideas to steer the game to more offense. One person found a way to excite the fans – Babe Ruth started playing more games in the outfield on days he did not pitch for the Red Sox. He liked the accolades for his home runs and swung for the fences. He hit 29 homers in 1919, more than anyone else had ever hit. That was one of the few bright spots for the year that became best known for the Black Sox scandal.

In 1920, a confluence of factors changed the game forever. Babe Ruth, now with the Yankees, continued to do his part by swinging away and connecting for 54 homers. But he was still an outlier – the second most was George Sisler with 19. Legendary hitters like Ty Cobb and Tris Speaker kept hitting for average and avoiding strikeouts. The Babe saw no shame in strikeouts as long as he gained fame with home runs. That plus his celebrity instincts helped reinvigorate baseball (reminder here, Jane Leavy will be in KC on October 24 to promote her new book Big Fella on this very subject).

There are also some yarns (pun intended) about a change in ball construction. One of the stories is that the manufacturer, Spalding, started using Australian wool to provide the strings of yarn that were wrapped around the core of the ball. This yarn was stronger and so could be more tightly wound – the result, a somewhat “livelier” ball. But a livelier ball at the start of a game was not enough. Sad to day, it took a dead man to cause the rule changes needed to truly start the “live-ball” era.

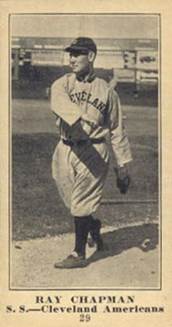

On August 16, 1920, Ray Chapman of Cleveland was at the plate facing the Yankees Carl Mays. Mays liked to pitch inside to intimidate batters, and he hit Chapman in the head, causing the only death of a player by a pitched ball in MLB history. It appeared that Chapman did not move before he was hit, so may not have seen the pitch or did not detect what may have been erratic movement (Mays also threw spitballs).

In those days, baseballs were not often changed during the game. Even foul balls hit in the stands were retrieved and stayed in play. In addition to the ball getting dirty from normal play, some pitchers would add substances, like tobacco juice, to further darken the surface. The ball became hard to see, especially on cloudy days or at twilight (there were no stadium lights). There was also the active and sometimes erratic ball movement caused by scuffing the ball or adding substances to create spitballs. Another major issue was that the ball (livelier or not) lost elasticity from continued use. These facts combined to create a “dead-ball” that favored pitchers over hitters.

The death of Chapman resulted in major rules changes. Umpires were required to frequently change to a new ball to assure that the ball in play was white for better visibility. This also meant it would not become soft from overuse. Starting with the 1921 season, spitballs were to be phased out. The “live-ball” era was born.

1968 – The Year of the Pitcher: In the 1920’s, the balance of power (pun intended) shifted to the offense. As the decades went by, there were changes to the rules, the ball and strategy that altered the balance from time to time. In 1968, pitchers reigned supreme. Why?

For the answer, I turn to Hall of Fame sportswriter Roger Angell and his New Yorker piece on the 1968 World Series:

“All the technical and strategic innovations of recent years have helped the defenses of baseball; none have favored the batter. Bigger ballparks with bigger outfields, the infielders’ enormous crab-claw gloves, more night games, the mastery of the relatively new slider pitch, the persistence of the relatively illegal spitter, and the instantaneous managerial finger-wag to the bullpen at the first hint of an enemy rally have all tipped the balance of the delicately balanced game.”

“The 1968 season has been named the Year of the Pitcher, which is only a kinder way of saying the Year of the Infield Pop-Up. The final records only confirm what so many fans, homeward bound after still another shutout , had already discovered for themselves; almost no one, it seemed , could hit the damn ball any more. The two leagues’ combined batting average of .236 was the lowest ever – four points below even the .240 compiled by the Mets in 1962, their first year of hilarious ineptitude…Carl Yastrzemski’s….average of .301 was the lowest ever to win a batting title.”

[Roger Angell Trivia: Angell turned 98 last month. His birth year of 1920 appropriately coincides with the beginning of the live-ball era. He blogged about the World Series last year, and I hope to see that again this year.]

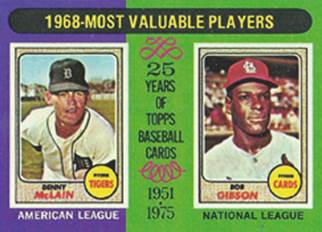

There were many pitchers who had great seasons in 1968, but three stood out:

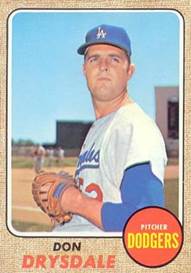

Don Drysdale of the Dodgers pitched 58 2/3 consecutive scoreless innings to break Walter Johnson’s record.

Denny McLain of the Tigers won 31 games. To this day, only three players have won 30 games in the live-ball era: McLain, Lefty Grove (31 in 1931), and Dizzy Dean (30 in 1934).

Bob Gibson of the Cardinals had an ERA of 1.12, by far the lowest in the live-ball era (still the record).

The baseball establishment was not that keen on The Year of the Pitcher. Shutouts were boring to many fans. So the game took a page from 1920 – the rules were changed. In 1969, the mound was lowered from 15” to 10” and the strike zone was changed from “between the top of the batter’s shoulders and his knees” to “between the batter’s armpits and the top of his knees.”

Gibson was not happy about that, but as Cardinal sportswriter Bob Broeg told him, “Goddam it Gib, you’re changing the game. It isn’t fun anymore. You’re making it like hockey.” And from Roger Angell, “Bob Gibson, we may conclude, was the man most responsible for the next major change in the dimensions of the sport.”

1968 – A Game with a Low ERA, A Country with a Low Era: I borrowed that title from somewhere on the internet. The country indeed had a rough year. Riots, assassinations, Viet Nam, Richard Nixon’s win, etc. Even baseball could not completely escape the turmoil.

After Martin Luther King was assassinated, his funeral was set for Tuesday, April 9. Opening days for the baseball season were set for April 8 and 9. Commissioner William Eckert initially left it to the team owners to decide whether or not to delay any openers. Some team owners cancelled, but some held out. Houston did not want to postpone their opener with Pittsburgh, but the Pirates players, led by Roberto Clemente and Maury Wills, unanimously refused to play. Dodger owner Walter O’Malley proposed a west-coast night game that would take place after the afternoon funeral. Sportswriter Dick Young of the New York Daily News wrote “It was as though someone was standing by the side of the bier with a stopwatch and a starter’s gun.”

Bob Gibson and other Cardinals met at the apartment of Orlando Cepeda and decided they would not play in the scheduled opener. “We’ve been waiting seven weeks, a day won’t matter,” Gibson told the Associated Press. Similar sentiments came from some teams, while others thought the games should be played. With all the turmoil, hard feelings and bad press, Eckert had little choice but to retreat and move back the entire slate of openers to Wednesday, April 10.

In less than two months, it happened again.

On June 4, Don Drysdale pitched a shutout against the Pirates in a night game at Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles. It was his sixth straight shutout, still the all-time record.

On that same night, Robert Kennedy was also in Los Angeles. It was primary election day and Kennedy was seeking the California delegates for the upcoming Democratic Convention. Drysdale and Kennedy were acquainted, originally meeting through the Job Corps program. Drysdale had been to Kennedy’s home in suburban Washington and they sometimes got together with mutual friends in California. In talking to reporters after his shutout that night, Drysdale had inquired “How’s the election coming out?”

Late that night, Kennedy was declared the winner. As the clock moved past midnight into June 5, Kennedy took the ballroom stage for his victory speech. The very first thing he said was…

“I want to express my high regard to Don Drysdale who pitched his sixth straight shutout tonight, and I hope that we have as good fortune in our campaign.”

He was sadly wrong on the “good fortune” for his campaign. Soon after the speech, Kennedy was shot. Drysdale heard the news on the radio as he drove home from the park. Kennedy died on June 6.

As had been the case with Martin Luther King, there was a question of baseball games being played. Kennedy’s funeral was set for Saturday, June 8, at St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York. His body was then to be taken by train to Washington for burial at about 5:00 at Arlington National Cemetery. Lyndon Johnson declared Sunday, June 9, as a national day of mourning.

Commissioner Eckert ordered that no game would start on Saturday until after the burial. Otherwise, he left it up to the management of each home club. The Giants wanted to play Saturday night, but the visiting Mets refused. The Cards did not want to play either Saturday or Sunday, but their Cincinnati host said all games were on. There were other variations that added up to baseball again embarrassing itself.

And then it got worse. The train carrying Kennedy’s body was delayed by large crowds as it made its way from New York to Washington. This delayed the burial for several hours. But parks were filling up with fans, and no one knew when the games would start. The Cardinal players again tried to get their game called off, but had to defer to the home team. The Reds players voted 13-12 to play, and the game got underway 45 minutes late.

The press was not kind. The Sporting News: “Baseball wallowed in a morass of confusion and acrimony…there was no concrete plan…”. The Cleveland Press: “Baseball’s observance of Senator Kennedy’s death was disorganized, illogical and thoroughly shabby.” It was no surprise when Eckert was fired a few months later.

One of the night games on June 8 was at Dodger Stadium, and as fate would have it, Drysdale was the starting pitcher. He needed to pitch shutout ball through the first seven outs to set a new record for consecutive scoreless innings. It was a bittersweet situation, and Vin Scully set the tone in his broadcast:

“They say the eye of the storm is the quiet part, and here, Dodger Stadium, has suddenly become the eye of the storm. A large crowd, approximately 50,000, and the winds of all kinds of emotions swirling around the ballpark. Certainly there are still the winds of sorrow; what a dreadful, drab and heartbreaking day it has been. But the gray skies now slowly start to disappear to night, so, too, the feelings in the ballpark are turning. And from almost the pits of despair, we concentrate on a child’s game – a ball, a bat and some people hitting it and catching it, and particularly Don Drysdale’s big night in baseball.”

Drysdale had watched the TV coverage of the funeral. At the game, he reflected his and the nation’s sorrow by wearing a black armband on his left, non-pitching arm. He pitched five scoreless innings before giving up a run, and that was more than enough. His consecutive scoreless inning streak ended at 58 2/3 innings, three innings more than the old record set by Walter “Big Train” Johnson in 1913.

MLB produced an excellent video with clips of the Kennedy speech interspersed with Drysdale’s pitching feats and Vin Scully’s game commentary. Well worth your time (5:30).

After his playing career, Drysdale became a broadcaster for several teams, and from 1988 to 1993, he broadcast for his Dodgers. This meant he was on hand to call the breaking of his own record. On September 28th, 1988, Dodger Orel Hershiser made his last start of the season. He entered the game with a streak of 49 consecutive scoreless innings. If he pitched a 9-inning shutout, he would reach 58 innings – just 2/3 of an inning short of Drysdale’s record. If he got the shutout, it appeared he would need to wait until the next season to go for the record. But then the improbable happened. Hershiser did pitch 9 innings of shutout ball, but his Dodgers also did not score. So he also pitched a scoreless 10th and got to 59 innings (one more out than the old record). He then came out of the game. The next season, he gave up a run in the first inning of his first game, ending his streak.

When the World Series starts this year, the coverage will no doubt include clips of famous Series moments. This means you will see for the umpteenth time Kirk Gibson pumping his arm as he rounds the bases after his walk-off homer in Game 1 in 1988. The play-by-play that goes with the TV clip features Vin Scully, but the radio broadcast by Drysdale was also worthy:

[Gibson enters the game as a pinch hitter] “Well, the crowd is on its feet and if there was ever a preface to ‘Casey at the Bat’ it would have to be the ninth inning. Two out. The tying run aboard, the winning run at the plate, and Kirk Gibson, standing at the plate. [play-by-play as Gibson works to a 3-2 count] Gibson, a deep sigh…re-gripping the bat…shoulders just shrugged…now goes to the top of the helmet, as he always does…steps in with that left foot. Eckersley working out of the stretch…here’s the three-two pitch…and a drive hit to right field…WAY BACK! THIS BALL…IS GONE! [followed by delay for crowd noise] This crowd will not stop! And this time, Mighty Casey did NOT strike out!”

In July of 1993, Drysdale was on the road to broadcast some Dodger games in Montreal. He died in his hotel room at age 56. Among his belongings in the room was a cassette tape of Robert Kennedy’s victory speech in Los Angeles. Drysdale apparently always carried the tape with him.

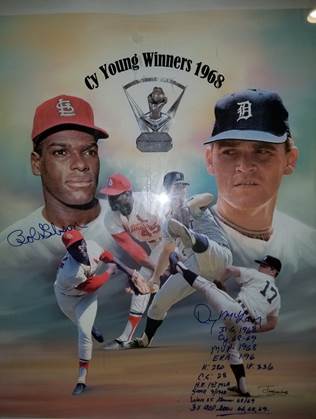

1968 World Series: Drysdale’s heroics were not enough for an otherwise poor Dodgers team – they finished 8th in the 10 team league. But the two big guns were going to the World Series. The 31 wins by McLain and the 1.12 ERA of Gibson not only got them the Cy Young Award for their league, they also were both named MVP. And they were poised to face each other in Game 1, Game 4 and, if necessary, Game 7 of the upcoming World Series. Potentially one of the all-time pitching duels. More about that in Hot Stove #85.

Lonnie’s Jukebox – Fifty Years Ago – The Smothers Brothers and “Hey Jude”: As McLain and Gibson approached their matchup in the Series, they were not the only notables making big plays in the fall of 1968. On September 30, Yale student Garry Trudeau published his first strip (about a quarterback named B.D.) that evolved into cultural icon Doonesbury – still going strong and one of my first things to read every Sunday morning. Over on the music calendar, the Beatles “Hey Jude” climbed the charts and was the number one song in the U.S. for nine weeks.

We were accustomed to the Beatles hitting #1, but “Hey Jude” really got “under your skin” – to borrow from McCartney – and you did feel “better, better, better…”. Beatles aficionado Paul Donnelly remembers where he was and who was driving when he first heard it. He also recalls the disc jockey commenting on its length. The song clocks in at a little over seven minutes, uncommonly long for a rock ‘n’ roll single.

My friend Bill Carr remembers where he was when “Hey Jude” was newly released. He was in New York on his honeymoon (married Robin on September 1), and the song was booming out from Tower Records and just about all of the other music stores. And if you are counting, you realize that Bill and Robin just celebrated their 50th anniversary. They returned to New York last month to mark their 50th and then continued on to Provence to extend the celebration.

I’m not sure when I first heard the record, but I know when it got under my skin. With Google reminding me of the date, it was on October 6, 1968, while I was watching The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour. A video of the song had run on David Frost’s show in England in September and then made its way to the Smothers Brothers’ show. I was captivated by Paul’s singing and the effect it had on the sing-a-long crowd that gathered around the band. I saw it on my low resolution black and white TV (like the photo below, see Paul at lower left). The original video was in color and has been updated in quality. Enjoy by clicking here.

Nah nah nah nah nah nah, nah nah nah, hey Jude…