I thought my collusion topic would be good for one post. But I kept getting intrigued by side stories. Oliver Wendell Holmes. Curt Flood. Catfish Hunter. Kirk Gibson. Andre Dawson. All those commissioners. Marvin Miller. The Brothers Fehr. Others who you will see below. So it has taken three posts. I don’t know what the next post will be about, but it won’t be this. Perhaps the Royals will surge.

As we left Part Two, the owners were still trying to blunt the effects of free agency after losing three straight years of collusion cases. After the collective bargaining agreement ran out at the end of 1993, the parties entered the1994 season far apart on terms for a new CBA.

Labor Unrest: The situation went from bad to worse as the parties could not agree on free agency, arbitration and revenue sharing. The sad result: The 1994 season ended on August 11 when the players went out on strike. The postseason was cancelled – the first year without a World Series since 1904. Below, the Fehr brothers in New York on December 22, 1994, the deadline date set by the owners for the players to give up many of the rights they had gained. The players said no, and the strike carried over into 1995.

The Brothers Fehr (Steve, at left, and Don)

David Cone – “This Statesman”: The American League Cy Young winner for the strike-shortened 1994 season was the Royals David Cone. The Kansas City native and Rockhurst High School grad was signed by his hometown Royals in 1981, and had gone on to play for the Mets and Toronto before returning to the Royals for the 1993 and 1994 seasons.

After the strike was called, Cone became “This Statesman” – the title to Chapter 16 in Roger Angell’s 2001 book, A Pitcher’s Story: Innings with David Cone. One of Angell’s sources for his book was Steve Fehr, Cone’s agent and a “source of balanced judgment and essential detail.” The quotes below come from Angell’s book.

Cone was one of two player reps for the Royals, but according to Steve Fehr, not a particularly avid or attentive one. Fehr invited Cone to get more involved after the strike started, “He was known and understood the issues. Of course we had no idea he would turn into this statesman.”

Cone moved into a prominent leadership role when he was selected by his fellow team reps to be the representative of the American League. He said that he found his new role almost overnight. “I’d had experience with the media in New York and could talk in complete sentences, and now suddenly everyone was saying ‘You can do it. You’ve got the balls and you don’t care – you be our front guy.’ And there I was, being interviewed by the national reporters or going on TV after another one of those deadlocked meetings.”

Don Fehr said “You have to have people like David Cone in this work. Players are strongly individualistic but also look for leaders…That was David.” Cone was sure of his cause, telling Roger Angell “The main issue in the strike was clear. This was a major effort by the owners to break the union. Some of them had been waiting years for the chance.”

After negotiations broke down at the end of 1994, some of the action moved to Washington for talks with the Clinton administration and Congress. The work with the politicians in 1995 provided no immediate relief for the strike, but it laid the groundwork for the passage in 1998 of the “Curt Flood Act” giving baseball players the same antitrust protection as other pro athletes.

[Memorabilia Trivia: In January of 1995, part of the wooing of Congress was a gigantic reception at D.C.’s Union Station. The celebrity appeal of meeting players drew a good crowd, including my friend Congresswoman Karen McCarthy who had just been elected. Each of the politicos was given a baseball for autographs, and Karen got a few. When she next returned to Kansas City, she gave the ball to her baseball nerd friend – me. Until I read Angell’s book, I had not fully appreciated how it fit in with the strike history. The autographs on my baseball: David Cone, Dave Winfield, Don Mattingly, Don Fehr and Karen McCarthy.]

District Judge Sonia Sotomayor: The owners made preparations to use replacement players to start the 1995 season. The union went to the National Labor Relations Board claiming that the owners were not negotiating in good faith (a/k/a colluding in bad faith). The NLRB agreed with the players, and the case moved to the Federal courtroom of New York District Judge Sonia Sotomayor.

Sotomayor also ruled for the players and issued an injunction on March 31 requiring the owners to start the 1995 season under the old CBA. She had acted quickly because opening day was near, noting that “I probably would have liked more time to practice my swing.” But as reported by George Vecsey in the New York Times: “Sotomayor did not need batting practice. She was like the rare hitter who can ‘wake up on Christmas Day and pull a curve ball,’ as the old saying goes. She saw the stiches and whacked it into the corner.” Other pundits noted that Sotomayor was a “heavy hitter on the bench” and had “moved into the early lead for an MVP award.”

Baseball was back. Below, Judge Sotomayor in 1995 (Courtroom sketch artist Marilyn Church).

1995 and 1996 – Albert Belle and Jerry Reinsdorf: With the strike ending on April 1, 1995, the season had a late start, so the schedule was reduced from 162 games to 144. Notwithstanding the shortened season, Albert Belle of the Cleveland Indians became the first player ever (and true to this day) to hit at least 50 doubles (52) and 50 home runs in the same season. He was also an RBI machine – 126 in 1995 and 148 in 1996. Please be patient, I will connect the dots.

The players and owners continued under the expired CBA as ordered by Judge Sotomayor. The owners tried to get her decision overturned in the 2nd Circuit, but they lost the appeal. Although the relationship between the parties was still very strained, there was a need to move forward with negotiations on a new CBA. And still in the mix was the warning from former commissioner Fay Vincent after the collusion cases of the 1980’s:

“The Union basically doesn’t trust the Ownership because collusion was a $280 million theft by Selig and Reinsdorf of that money from the players. I mean, they rigged the signing of free agents. They got caught. They paid $280 million to the players. And I think that’s polluted labor relations in baseball ever since it happened. I think it’s the reason Fehr has no trust in Selig.”

I am repeating this quote from Part Two to focus on Jerry Reinsdorf, the owner of the Chicago White Sox. He was one of the hardliners in dealing with the players, working closely with fellow owner Bud Selig who moved into the commissioner’s chair in 1992. Some thought Reinsdorf was the puppeteer of Selig and it was said that “people are amazed at how little Reinsdorf’s lips move when Selig speaks.” A few days before Judge Sotomayor issued her 1995 injunction, Reinsdorf compared Don Fehr to Jonestown cult leader Jim Jones and wondered if Fehr was offering Kool-Aid to the striking players.

By October of 1996, a tentative agreement was reached by the negotiating committees headed by Don Fehr for the players and chief negotiator Randy Levine for the owners. On November 6, the owners voted 18-12 in favor of the agreement, but their by-laws required a supermajority of 23 for approval. Reinsdorf lobbied against the agreement, saying “we need some meaningful salary restraint and sharing of revenue.” Thirteen days later, Reinsdorf signed controversial free agent Albert Belle to a 5-year contract for $55 million dollars, the richest in baseball history (plus an unusual guaranty – Belle could request an increase over the term as necessary to keep him in the top three salaried players in baseball). As noted by one pundit, “To his peers Reinsdorf would not have appeared more duplicitous if had been caught in a hot tub with Don Fehr.”

Within days, the owners (still over the objection of Reinsdorf) ratified by a 26-4 vote what had been negotiated in October. Reinsdorf had not helped his cause, but defended the Belle signing as just moving forward when he could tell the owners “were caving” on the CBA. Belle and White Sox first baseman Frank Thomas would together make $18 million in the coming season, an amount exceeding the whole payroll of four small-market teams, including Selig’s Brewers.

It did not work out that well for Reinsdorf. Although Belle did his part, over 100 RBIs each year, the White Sox dropped to below .500 the next two seasons. Some players on other teams by then had a higher salary than Belle, and so he invoked his right to an increase in salary. The White Sox declined, giving Belle the right to again become a free agent. He signed an even bigger contract with Baltimore and returned to being the highest paid player. He lasted only two years before injuries forced him into retirement. Belle’s long list of controversies meant he would not be missed by the press and some players. As summed up by one sportswriter: “Sorry, there’ll be no words of sympathy here for Albert Belle. He was a surly jerk before he got hurt and now he’s a hurt surly jerk…He was no credit to the game.”

It would appear that Belle did not mellow after leaving baseball. In 2006, he was convicted for stalking a former girl-friend. Two months ago, he was arrested for indecent exposure and driving under the influence. But hey, his contract with Reinsdorf put new life in the settlement negotiations for a new CBA that covered six seasons (1997-2002).

The Gang of Four: In 2002, the last season under the existing CBA, both sides knew they had to reach an agreement without any work stoppage. Attendance and TV ratings had plummeted after the 1994 debacle. In July, the union’s Michael Weiner and Steve Fehr and MLB’s Bob DuPuy and Rob Manfred met to jump-start talks for a new agreement. They were called the “Gang of Four” and are given credit for pounding out an agreement that was approved by the players and 29 of the 30 owners (George Steinbrenner was the no vote – he did not like the revenue sharing formula).

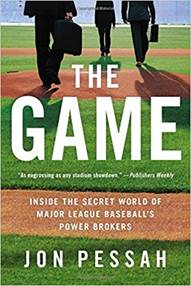

In Jon Pessah’s book The Game: Inside the Secret World of Major League Baseball’s Power Brokers, there is a blow-by-blow account of the negotiations through July and August of 2002. The heavy lifting was left to the Gang of Four as Don Fehr and Commissioner Selig remained in the background (not much trust – see Fay Vincent quote above). In an article in Sports Business Journal, MLB’s Rob Manfred said Steve Fehr was instrumental in getting a deal done, serving as “calming force” in the “the most important thing he has done.” Manfred did okay for himself too. He became Commissioner Manfred in 2015.

Today in Baseball: There has not been a work stoppage since 1995, but as one pundit has noted, there is no true labor peace in MLB: it’s simply the time in between negotiations where ownership regroups to figure out how they can scale back gains of the players. Certainly the poor market for free agents this year has again raised the specter of collusion. Or maybe the true issue is that there needs to be a reallocation of baseball revenues. If older free agents are going to get less, players in their prime should get more. Revenue sharing between small and big markets may need a tweak. It’s all very complex, and Commissioner Rob Manfred and Executive Director Tony Clark have their work cut out for them.

[Brothers Fehr Trivia: Don Fehr retired in 2009, but a year later took on a new sport by becoming Executive Director of the NHL Players Association. Steve Fehr serves as outside counsel for that entity. The photo below shows the two Fehrs in their hockey lawyer uniforms – Steve in the middle and Don on the right.]

Miller/Fehr/Heeter Licensing Legacy: One of Marvin Miller’s first moves in 1966 was do what he could to help players get a fair return for the use of their images. It started with baseball cards and expanded to other areas. Two lawyers from Kansas City then took it to another level.

Don Fehr graduated from law school at the University of Missouri at Kansas City in 1973. His first position was clerking for Western District Judge Elmo Hunter, and he helped recruit his replacement, Judy Heeter, also a UMKC graduate. Don moved on to a Kansas City labor law firm which led to working as local counsel on the Messersmith free agent case and then to in-house general counsel and ultimately Executive Director of the MLBPA. After Judy’s clerkship, she went to work at Hallmark where she became the lead licensing lawyer. In 1989, she joined KC law firm Shughart, Thomson and Kilroy.

In 1990, Fehr was looking for a lawyer to help with the expanding field of protecting and marketing players’ rights to their names and images. He reached out to Judy to see if she might apply her Hallmark licensing expertise to baseball players. And that’s how Judy Heeter and the Shughart firm began their long relationship with the union. Coincidentally, the Shughart firm had represented the owners in the Messersmith case in 1975 (on the other side of the table from Don Fehr).

Judy’s early work included an audit of the four baseball card companies that resulted in additional millions of dollars for the players. With the growth potential for licensing, she was soon asked to join the staff of the MLBPA as the Director of Business Affairs and Licensing. She enlisted several of her Shughart colleagues to work on a wide range of MLBPA matters, but maybe the best shorthand way to tell the story is this: during her tenure (1990-2010), the group licensing program diversified well beyond baseball cards and increased from $50 million per year to $800 million at retail per year. Another benefit was that it gave the union significant revenues for a meaningful strike fund to pay players and help them stay unified as they did in the 1994-95 strike.

Photo below from a 2006 Kansas City Business Journal article titled “For licensing deals, the players bring the Heeter.”

Judy left her position with the union in 2010 and left Shughart in 2011. She now advises a variety of clients in strategic business matters and serves as a director of two public companies.

[Lawyer Trivia: By pure coincidence, Judy was my partner for the last year of her work for the union. On February 1, 2009, Shughart merged with Polsinelli, Shalton, Flanigan and Suelthaus to create a newly named firm, Polsinelli Shughart. Although Judy left the firm in 2011, many of her Shughart colleagues who worked on MLBPA matters still roam the halls with me here at the Polsinelli building – Russ Jones, Larry Swain, Jeb Bayer, etc.]

Hall of Fame: Former commissioners Bowie Kuhn and Bud Selig, big losers in the baseball labor battles, are in the Hall of Fame. Marvin Miller is not. A travesty. Even Bud Selig thinks Miller should be in.

Baseball’s top stats guru, Bill James, wrote the introduction to Miller’s autobiography, A Whole Different Ball Game: The Inside Story to the Baseball Revolution. James’ first sentence: “If baseball ever buys itself a mountain and starts carving faces in it, one of the first men to go up is sure to be Marvin Miller.” Hall of Fame broadcaster Red Barber has said that the three most important people in baseball history are Babe Ruth, Jackie Robinson and Marvin Miller. I agree with both of them, and so my personal baseball Mount Rushmore would be Ruth, Robinson, Miller and a player or executive to be named.

Marvin Miller has been on several HOF Veterans Committee ballots, but that has often been a stacked deck. For example, in 2008, the 12-person committee had seven owners/executives, three writers and two players from the pre-Miller era. Miller and Bowie Kuhn were both on the ballot. Miller got only three votes, while Kuhn was voted into the Hall of Fame. Miller died in 2012, and so any correction of this travesty will need to be a posthumous award.

Justice Sotomayor Trivia: President Obama called Sonia Sotomayor up to the big leagues in 2009. In his Supreme Court nomination, Obama said that some would say Sotomayor saved baseball. He was of course referring to her 1995 decision ordering the teams to open the season. David Cone agreed with Obama and testified (below) before the Senate at Sotomayor’s confirmation hearing. Click here for a short clip of his testimony. The person behind Cone’s left shoulder is the ubiquitous Steve Fehr.

A month after joining the Supreme Court, the Bronx-born Justice Sotomayor threw out the first pitch at Yankee Stadium.

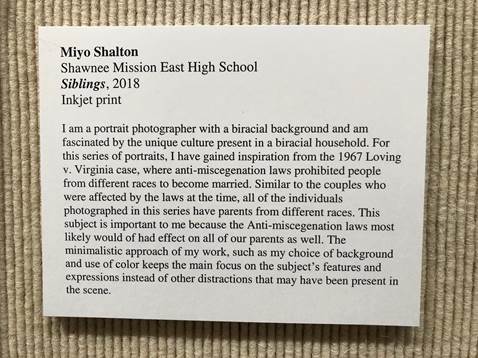

Lonnie’s Jukebox – Miyo: For this post, I’m switching the jukebox from music to the visual arts.

My granddaughter Miyo (18) was born in Japan and the family moved to Kansas City when she was 10. She initially concentrated on ballet and performed in the Kansas City Ballet’s Nutcracker on the stages of the Folly Theatre and the Kauffman Center. She is also a budding photographer and is one of 15 high school students selected this year for the Nelson-Atkins Photography Scholars Program. This eight-week program recently ended, and the results are featured in a wonderful exhibition at the Nelson.

Rita and I went to the opening of the exhibit and were blown away. But not just because of the photos.

Each student chose a theme that has a personal significance and then transformed that theme into an “artist statement” and a series of photos.

Miyo’s work is about the unique culture present in a biracial household. Her father is my son Jason and her mother Mika is Japanese. The parents met while attending the Berklee College of Music in Boston.

Each artist has a photo in the exhibition posted next to their artist statement. Other themes include racial segregation (the Troost line), mental illness, the environment and school shootings. Their insight, social awareness and sense of history is so much more advanced than the “adults” might think. It made me realize that the Parkland students are not some aberration.

If you get a chance, the exhibit continues until June 18. It is located in the Ford Education Center near the main desk in the Block Building. No admission charge.

It will make you proud of this upcoming generation. I know I am.

Below, (i) Miyo with one of her photos, (ii) her artist statement, and (iii) her photo of her brother Ian.

[Ian Trivia: Early followers of Hot Stove may recall a series of posts in which my grandson Ian and I picked an all-time MLB team. We were in agreement on Ted Williams (LF), Willie Mays (CF), Yogi Berra (C), Lou Gehrig (1B), Honus Wagner (SS) and George Brett (3B; a shameless parochial choice over Mike Schmidt). We differed on two, but I can hardly quarrel with his choices. At 2B, after recognizing that Rogers Hornsby was likely the best, we limited our choice to “modern” players – his pick was Jackie Robinson, mine was Joe Morgan. In RF, he picked Hank Aaron over my Babe Ruth.

You also have seen Ian in some little league baseball photos, and he is again playing this season. When Hot Stove started, he was 10 and the Royals had just won the World Series. He assumed the winning ways would continue. Ian is now 12 and has learned that life throws some curves. For years, Ian has been a subject of unique photos taken by his sister Miyo. As you see above, that continues.]