[Below is this year’s message for Martin Luther King Jr. Day. This continues an annual tradition started in 2002 when I posted an internal message at my law firm about the MLK holiday. The message expanded to friends and family, and in 2016, it moved to Hot Stove.]

Over Labor Day Weekend of 2023, Rita and I attended the Telluride Film Festival. One of the films we saw was Rustin, a biopic about Bayard Rustin, an unsung hero of the Civil Rights Movement. As soon as I saw the movie, I knew he would be the subject of my 2024 MLK message.

After its world premiere at Telluride, Rustin opened in theaters on November 3 and is now streaming on Netflix.

In my Telluride film reviews in Hot Stove, here is what I said about Rustin…

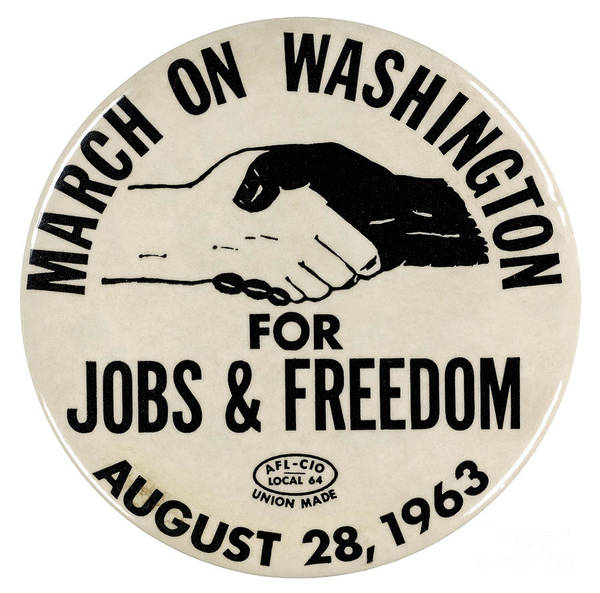

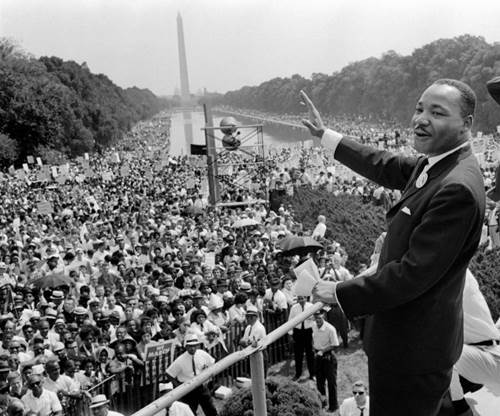

The 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom is best known for Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech and the impact the march had on pushing Congress into action on civil rights.

Who conceived the march? Who organized the logistics that came together and drew 250,000 people to the Lincoln Memorial? Who had to overcome obstacles thrown up by those within and outside the movement?

Bayard Rustin, a name often lost in the telling of this event. Why? Rustin was gay and could not be the up-front person for media purposes. This was the ‘60s. Rustin tells this important story, and Colman Domingo (below) in the title role is a worthy challenger to Cillian Murphy (Oppenheimer) for best actor. The large cast includes Chris Rock as NAACP head Roy Wilkins.

The movie was directed by George C. Wolfe (Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom), and he attended our screening to introduce the film. Rustin is produced by Barack and Michelle Obama’s Higher Ground Productions, and Barack Obama did an introductory clip for the screenings at Telluride.

Rustin’s Early Activism: The movie focuses on the 1963 march, but the full story of Bayard Rustin involves decades of activism for many causes.

He had an early mentor. He was raised by his grandparents, and his grandmother was a Quaker and a member of the NAACP. Leaders of the NAACP (e.g., W. E. B. Du Bois) were guests in the family home. Quaker pacifism became a major influence in Rustin’s embrace of nonviolence in protesting social injustice.

As a youth, Rustin campaigned against Jim Crow laws. In the mid-1930s, he attended Wilberforce University but was kicked out for organizing a strike against bad food in the dorms (a precursor to his later organizing).

Rustin moved to Harlem and became active in Quaker and civil rights causes. He joined the Young Communist League which was supportive of civil rights for African Americans and had an anti-war policy. But that anti-war policy changed after Germany invaded the USSR, and Rustin moved on. He began working with activists of the Socialist Party and met his next mentor, A. Philip Randolph, founder of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters.

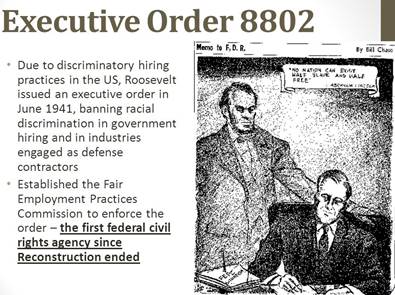

1941 March on Washington (Not): In early 1941, Rustin, Randolph and pacifist A. J. Muste organized a march on Washington to protest segregation of the armed forces and discrimination in employment. The march was scheduled for July 1, but was cancelled when President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802 prohibiting discrimination in the defense industry (by companies, unions and federal agencies). Rustin opposed the cancellation because the armed forces remained segregated, but the order was a partial win, the first executive civil rights directive since Reconstruction.

In the fall of 1941, Rustin joined the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR), a pacifist organization, and in 1942 co-founded the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). Rustin was an organizer for both organizations and travelled the country to give workshops and lectures on nonviolent activism. This included visiting conscientious objectors in Civilian Public Service (CPS) camps and Japanese Americans in internment camps (set up by FDR’s Executive Order 9066).

Rustin was an excellent organizer, but his work was harshly interrupted…

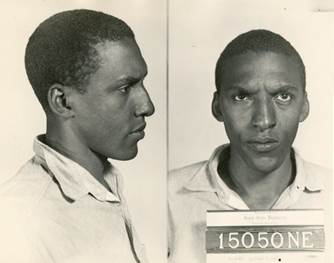

1944 – A Pause for Jail: Living his beliefs, Rustin was a conscientious objector and refused to report for the draft. He also refused sequestration in a CPS camp. So, he was imprisoned from 1944 to 1946, during which time he was disciplined many times for protesting the segregation and condition of the facilities. He was officially labeled a “notorious offender,” and this was compounded by homophobia because Rustin did not hide that he was gay.

Nonviolent Protesting and Harry Truman: In 1947, Rustin helped organize one of the earliest nonviolent protests in the Civil Rights Movement. It was the Journey of Reconciliation (a/k/a “First Freedom Rides”) when fourteen men, equally divided by race, tested the right to travel together on interstate transportation. There were many arrests, and one put Rustin on a chain gang in North Carolina for 22 days.

In 1948, as a new military conscription bill was being considered, Black leaders pressured President Harry Truman and Congress to include language for desegregation of the armed services. In March, A. Philip Randolph met with Truman and went before a Senate committee to threaten that Black conscripts would refuse the draft if the bill did not provide for desegregation. The bill passed in June without the requested provision.

Two of the primary organizations protesting the passage of the bill were led by Randolph and Rustin, and they joined forces to apply civil disobedience to the cause. Among other acts, they picketed the 1948 Democratic Convention in Philadelphia, and on July 13, were joined on the picket line by a white man they did not know. The man introduced himself. He was Hubert Humphrey, the young mayor of Minneapolis who the next day would deliver his impassioned plea for a civil rights plank in the platform (he got it, prompting delegates from the South to walk out and form the Dixiecrats to support Strom Thurmond for president).

Two weeks later, on July 26, Harry Truman signed Executive Order 9981, integrating the armed services. Truman was especially offended by the harsh treatment of Black soldiers returning from war, but the pressure from the likes of Randolph and Rustin no doubt played a role. And it was an election year.

Randolph considered this a victory that should be treated as such. But Rustin felt just like he had with FDR’s order in 1941. The pacifist Rustin wanted more and chastised Randolph for giving in. Rustin and his followers continued conscription protests, and he was jailed 15 days in New York for disorderly conduct.

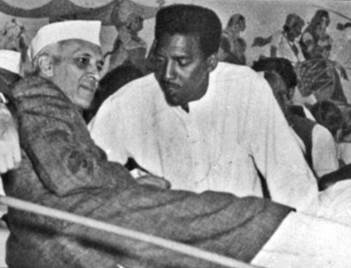

After his release from jail, Rustin travelled to India where his seven-week visit included becoming more educated in the Gandhian philosophy of nonviolent civil resistance. Rustin had supported India’s independence movement and met with Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first prime minister. [At the Golden Globe awards this past Sunday, Colman Domingo wore a custom Nehru jacket because Nehru “was a colleague of Bayard Rustin, who I am representing tonight as a leading actor in a film…[Nehru] represented peace and strength and love.”]

Rustin continued his involvement in many areas, but his good work was again harshly interrupted. In 1953, he was arrested in Pasadena, California, for sexual activity in a car. He pled guilty to a reduced charge of “sex perversion.” This caused some organizations in the movement to shy away from Rustin, but his talents were too good to ignore. The War Resisters League hired him in 1953, and during his 12 years there, he was often granted leave to continue his civil rights work.

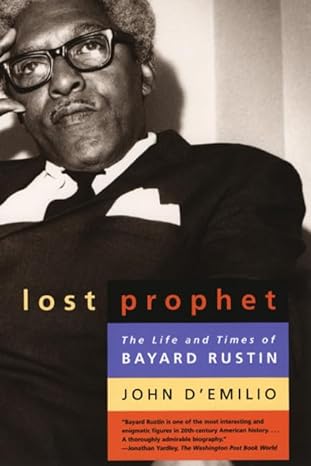

Martin Luther King Jr.: At the suggestion of A. Philip Randolph, Rustin went to Alabama in 1956 to support Martin Luther King Jr. in the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Rustin and King met frequently, and Rustin initiated the process of transforming King into the best-known proponent of nonviolent protest. Although King had an academic understanding of Gandhi, he was not schooled in nonviolent tactics. As recounted in John D’Emilio’s biography of Rustin (Lost Prophet), Rustin said…

“We hit it off immediately, particularly in terms of the whole concept of nonviolence. The fact of the matter is, when I got to Montgomery, Dr. King had very limited notions about how a nonviolent protest should be carried out…The glorious thing is that he came to a profoundly deep understanding of nonviolence through the struggle itself.”

King was warned by many that the presence of Rustin could be detrimental to the movement (gay, jail, former communist). But the young Dr. King had found an experienced mentor who helped King make nonviolence a cornerstone of the Civil Rights Movement. At the urging of Rustin, and with guidelines outlined by Rustin, King founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) in 1957.

Although their relationship was sometimes tenuous, Rustin remained a friend, confidant and advisor to King until King’s assassination in 1968.

School Integration Marches: Brown v. Board was decided in 1954, but school integration was proceeding at a glacial pace. This gave Rustin his opening to finally organize a march on Washington. Three years in a row.

After being rebuffed by President Eisenhower on civil rights matters, the SCLC and NAACP held a “Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom” on May 17, 1957 (the third anniversary of Brown v. Board). Rustin was instrumental in organizing the event which drew 25,000 to Washington, the biggest civil rights demonstration to that date. A national audience saw Martin Luther King Jr. deliver his famous “Give Us the Ballot“ speech.

In 1958, working closely with his old friend A. Philip Randolph, Rustin organized a “Youth March for Integration,” drawing 10,000 young people to Washington. A second youth march in 1959 drew a crowd of 25,000.

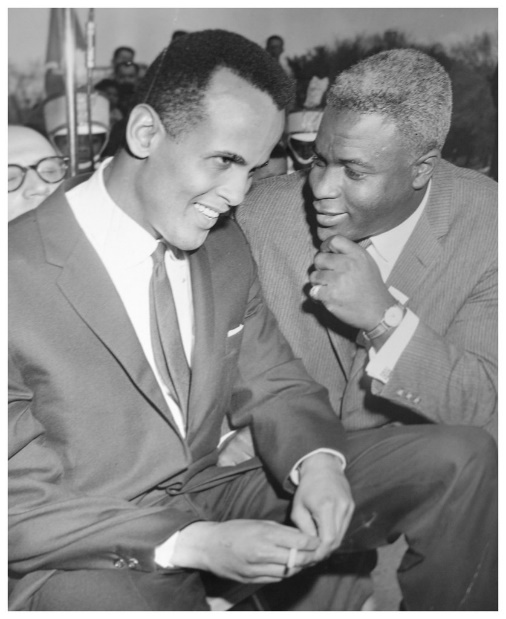

Rustin was savvy about drawing celebrities to events for good publicity. Two of his recruits for the youth marches were Harry Belafonte and Jackie Robinson (below, at the 1958 march). They would both also attend the 1963 march.

Jackie Robinson was familiar with the glacial pace of integration. He had integrated “organized” baseball in 1947, but most teams did not participate until the 1950s. The Red Sox were the last holdout, integrating in 1959, 12 years after Jackie’s debut.

The same gestation period of 12 years applied to Harry Truman’s order on the armed forces in 1948. The Marines did not fully integrate until 1960.

The flaunting of “all deliberate speed” as called for in Brown v. Board was universal.

1960 March on the Democratic Party (Not): In 1960, Rustin and King planned a civil rights march on behalf of the SCLC outside the Democratic National Convention in Los Angeles. Congressman Adam Clayton Powell objected and threatened to leak fake rumors of an affair between Rustin and King. King bowed to the pressure, and the march was cancelled. Devastated, Rustin left his position in the SCLC.

But Rustin never stopped working, and his tour de force was coming…

1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom: In December of 1961, Rustin and Randolph started planning their next march on Washington. Having already confronted Presidents Roosevelt, Truman and Eisenhower, it was now time to nudge President John Kennedy. The focus was to be on jobs and employment discrimination, but as the coalition developed over the next year, a broader civil rights agenda was adopted.

The coalition was led by the “Big Six” of A. Philip Randolph, Martin Luther King Jr. (SCLC), James Farmer (CORE), John Lewis (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee), Roy Wilkins (NAACP) and Whitney Young (National Urban League). Randolph proposed Rustin to be the organizer of the march, but Wilkins and Young objected (for the usual reasons). Randolph was adamant and said he would take on the public role as the organizer, but only if Rustin could be his deputy and oversee the logistics.

Senator Strom Thurmond was no fan of the march. He went to the floor of the Senate to accuse Rustin of being a “sex pervert” and a “draft dodger.” He placed info on Rustin’s arrests and other history in the Congressional Record. His source was the FBI where J. Edgar Hoover was running a comprehensive operation of surveillance and wiretapping of civil rights leaders.

Thurmond proved to be the perfect enemy. A Washington Post column gave much of Thurmond’s info a positive spin, noting that Rustin had made a decisive break with communism and most of the arrests were on behalf of peace and racial justice. Randolph defended Rustin at a press conference, and the coalition did not back down. Thurmond failed just like he had when he ran against Truman in 1948. Poetic justice for a racist hypocrite.

Speakers at the march included the Big Six plus four white leaders (together, the “Big Ten”). The four were UAW President Walter Reuther and three religious leaders (Catholic, Protestant and Jewish). Many celebrities were in the crowd and several singers performed (see Lonnie’s Jukebox below).

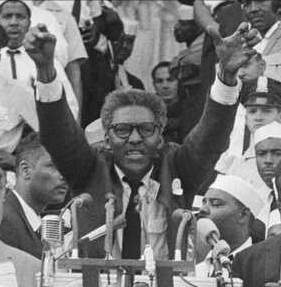

The march was a huge success, drawing 250,000 people and capped off with Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech. Rustin even had a public role, taking the podium to list the specific demands being made (video here).

It proved to be a watershed event in the Civil Rights Movement, ultimately pressuring and persuading President Lyndon Johnson to champion and pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

For more details on the march, I recommend that your upcoming holiday weekend include a viewing of Rustin on Netflix.

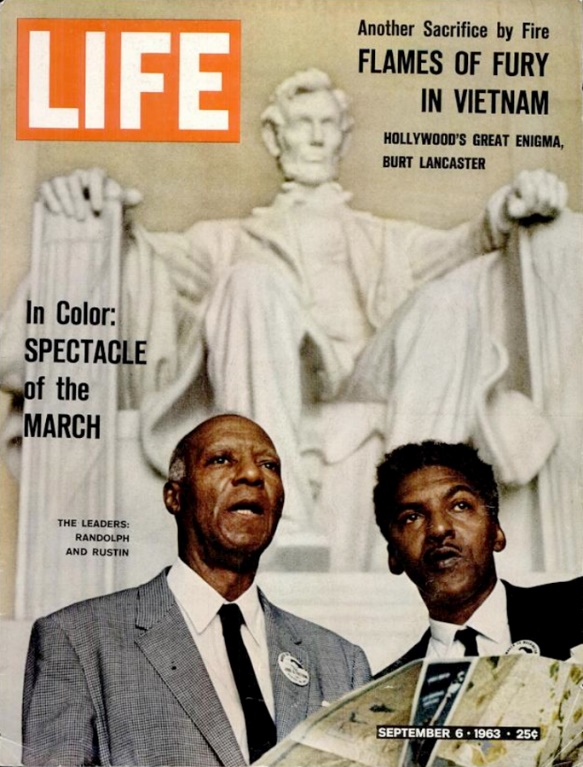

Bayard Rustin, the man “behind the scenes,” finally got some public recognition, including this cover of Life. “THE LEADERS RANDOLPH AND RUSTIN.”

As Taylor Branch wrote in his epic MLK trilogy: “The outcome so embarrassed predictions that march organizer Bayard Rustin gained credit as a fresh wizard of social engineering, whose command of scheduling and portable toilets had worked a miracle on the races. Overnight, Rustin became if not a household name at least a quotable source for racial journalism, his former defects as a vagabond ex-Communist homosexual henceforth overlooked and forgiven.”

But “defects” being “overlooked and forgiven” was an optimistic view that was not to be. Prejudice is hard to overcome.

1965 Selma to Montgomery March: Rustin was involved in the strategy of the Selma voting rights campaign, consulting with King and Andrew Young (SCLC’s executive director). Below, at one of the Selma events, he is at the far left, next to John Lewis. On the right are Martin Luther King Jr. and his wife, Coretta Scott King. Rustin was also proud to be part of the entourage in the Oval Office when President Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

But Rustin did not play the leadership role as he had in the 1963 march. He had been proposed as the chairman of the Selma campaign, but the old prejudices returned. He was again pushed aside.

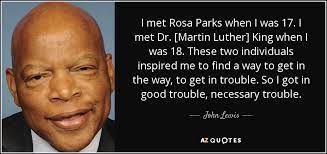

John Lewis still remembered this slight in 1996 during the legislative battle over the mislabeled Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA). Lewis said DOMA gave him the same feeling in the pit of his stomach as when civil rights leaders opposed Rustin as chairman of the Selma march. “[Rustin] was pushed aside. He was brilliant, but they thought it would hurt the movement – that certain senators would use it against the march. It was wrong.”

Speaking on the House floor in opposition to DOMA, Lewis said, “I have fought too hard and too long against discrimination based on race and color not to stand up against discrimination based on sexual orientation. Mr. Chairman, I have known racism. I have known bigotry. This bill stinks of the same fear, hatred and intolerance. It should not be called the Defense of Marriage Act. It should be called the defense of mean-spirited bigots act.”

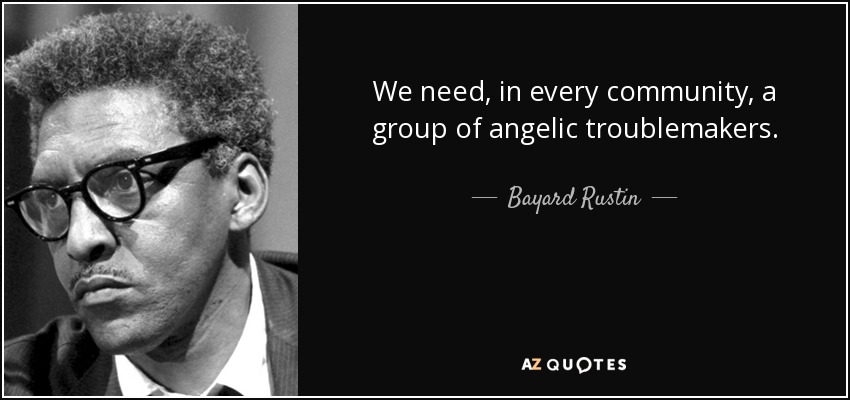

The often-quoted mantras for Lewis and Rustin show how they shared a similar approach to activism. Trouble!

When Rustin came back from India in 1948, he wrote, “We need in every community a group of angelic troublemakers. The only weapon we have is our bodies, and we need to tuck them in places, so wheels don’t turn.”

Lewis mentioned “good trouble” so often that it is the title of the 2020 documentary about his life.

One of the joys of my life was seeing John Lewis talk about “good trouble” at a Truman Library event in 2017 (below, Lewis with Congressman James Clyburn and interviewer David Von Drehle).

After Selma: Rustin rarely slowed down for the next 20 years. After Dr. King was assassinated in 1968, Rustin worked less with the traditional civil rights leadership. He charted his own course and worked in a variety of social justice and human rights matters. A partial list: the labor movement, international affairs (e.g., support of Israel), refugees, apartheid, party politics, etc. Way too much to cover in a Hot Stove.

When his civil rights recruit Jackie Robinson died in 1972, Rustin was part of the big crowd gathered for the funeral at Riverside Church in New York. Ever the organizer, the New York Times reported, “More celebrities crowded into the waiting room as Bayard Rustin, the civil rights leader, tried to smooth out the logistical problems.” Below, Jackie’s Dodger teammates and Bill Russell are pallbearers at the funeral. Rustin is the white-headed man standing in the right foreground.

In 1977, Rustin met Walter Naegle who would be his partner for the remainder of his life. With the support and urging of Naegle, Rustin became more active in the gay community and in supporting gay rights. He gave speeches and used his influence and connections to further the cause.

One example was during the AIDS crisis in the 1980s. Rustin lobbied Mayor Ed Koch and the city council to add sexual orientation to the list of protected categories in the human rights codes. He told reluctant African American council members that opposing the bill would be “tantamount to the filibustering that succeeded in blocking the Civil Rights Legislation in the U.S. from 1876 until 1964…History demonstrates that no group is ultimately safe from prejudice, bigotry and harassment so long as any group is subject to negative special treatment.”

In an interview, Rustin said, “In the 1960s, the barometer of people’s thinking was the Black community. Today [the 1980s], the barometer of where one is on human rights questions is no longer the Black, it’s the gay community.”

On March 19, 1987, Rustin turned 75 and was feted with a party of 600 guests and a formal dinner at the New York Hilton. His next trip was to Haiti to monitor elections, but he and Naegle both fell ill. After returning to New York, Naegle was soon better, but a series of complications caused Rustin’s death on August 24, 1987.

Final Word from Bayard Rustin: John D’Emilio’s biography ends with a couple of quotes. The first is one Rustin was fond of repeating and attributed to A. Philip Randolph…

“The struggle must be continuous, for freedom is never a final act.”

The other is a quote from Rustin after he was asked how he kept hopeful in dismal times…

“I have learned a very significant message from the Jewish prophets. They taught that God does not require us to achieve any of the good tasks that humanity must pursue. What the gods require of us is that we not stop trying.”

Lonnie’s Jukebox (1)– Rustin and Obama: In August of 2013, marking the 50th anniversary of the 1963 march, President Barack Obama announced that Bayard Rustin would be posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom. The ceremony took place at the White House in November (video here).

Ten years later, Barack and Michelle Obama’s Higher Ground Productions released the biopic Rustin.

“King to March” and “Rustin Shuffle” – Two short clips from the score by Branford Marsalis.

“Road to Freedom” (as performed on Jimmy Kimmel Live! – excellent). This original song was written and performed for the movie by Lenny Kravitz. Director George C. Wolfe asked Kravitz to move audiences from feeling to action, suggesting the use of trombones. Wolfe: “Lenny took my request to the next level and brought on board the legendary Trombone Shorty. ‘Road to Freedom’ captures both 1963 and 2023; a bold celebration, as Lenny’s voice sermonizes and soars.”

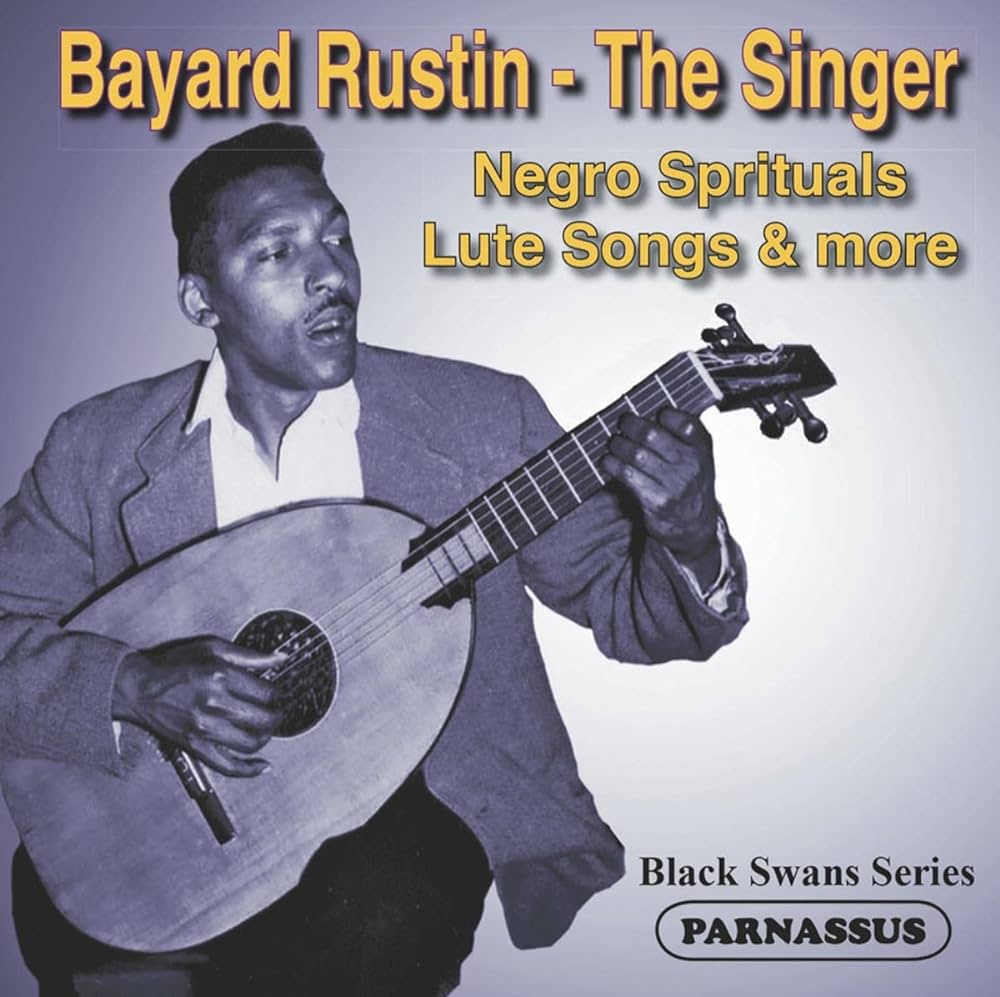

Lonnie’s Jukebox (2): Rustin the Singer: Bayard Rustin had a fine tenor singing voice and appeared in the chorus of a Paul Robeson musical on Broadway in 1939. With contacts he made there, he performed and recorded with a group that played at Café Society, an integrated club in Greenwich Village. He also did some individual recordings. Here’s a sample:

“Swing Low Sweet Chariot” by Bayard Rustin.

“You Don’t Have to Ride Jim Crow” by Bayard Rustin. The clip begins with Rustin introducing the song, which he co-wrote. “You can sit anywhere…someday we’ll all be free.”

Lonnie’s Jukebox (3)– 1963 March Edition: In addition to the speeches at the 1963 march, there were several music performances. Here are a few.

“I’m on My Way” by Odetta.

“We Shall Overcome” by Joan Baez.

“How I Got Over” by Mahalia Jackson.

“When the Ship Comes In” by Bob Dylan. In the clip, Joan Baez joins Dylan on stage, and Bayard Rustin can be seen behind them (dark glasses). He then walks away (smoking a cigarette).

Dylan also sang “Only a Pawn in Their Game” about the murder of Medgar Evers. Soon after the march, Dylan wrote “The Times They Are a-Changin’” which became an anthem for the civil and political unrest in the 1960s. All three of these Dylan songs were on his next album, The Times They Are a-Changin’ (1964).

“He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands” by Marian Anderson. In 1939, Anderson was denied access to sing at Constitution Hall in Washington D.C. Only white singers were allowed to perform at the 4,000-seat concert hall owned by the Daughters of the American Revolution. Eleanor Roosevelt pushed for a change of policy but was rebuffed. With the assent of her husband, Eleanor arranged for Anderson to perform at the Lincoln Memorial where she drew a diverse crowd of 75,000 and a radio audience of millions. She sang “The Star-Spangled Banner” at the inaugurations of Dwight Eisenhower (1957) and John Kennedy (1961).

“Blowing in the Wind” by Peter, Paul and Mary. Written by Bob Dylan, the song inspired Sam Cooke to write his own civil rights anthem, “A Change is Gonna Come.”

“We Shall Not Be Moved” by the Freedom Singers.

While enjoying your upcoming holiday weekend, please make a toast to Bayard Rustin. And cheer for the Chiefs!