Part One (in Hot Stove #172) covered the World Series of 1921 and 1946. In this Part Two, we’ll look at 1971 and 1996.

This will give you something to read between innings and during the many, many pitching changes as we finish working through the ALCS and NLCS. I’ll recap those games next week, but want to share one ALCS anecdote from two days ago.

On Tuesday, there were two games that each exceeded four hours. No, we didn’t watch all eight hours, but still quite a bit. As the Boston/Houston game went into the 9th inning on Tuesday night, I was getting ready for bed with the bedroom TV on. I noticed that there were a lot of deuces on the scoreboard (one of my obsessive traits).

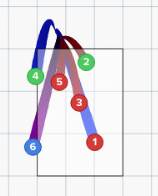

The score was 2-2. There were two out and two men on (the yellow bases at the bottom of the scoreboard icon). Jason Castro was at the plate for Houston and Nathan Eovaldi was on the mound for Boston. The count was 1-2, but it became 2-2 when a ball was called on the next pitch. I did not focus on whether the pitch should have been called a strike. I was concentrating on the scoreboard and took a photo of my TV screen to show the six deuces.

If the pitch had been called a strike, the inning would have been over and Boston would have gone to bat in the bottom of the 9th tied 2-2. A walk-off win in the making for the Fenway crowd.

Not. With the pitch called a ball, Castro was still at the plate and fouled off the next pitch. He then singled to score Carlos Correa from second, and Houston took a 3-2 lead. Things then fell apart. Houston scored six more runs in the inning for a 9-2 lead. That’s how it ended, and Boston’s big chance for a 3-1 ALCS lead was instead a 2-2 tie with three games to go. After Houston’s win last night, the Astros have a 3-2 ALCS lead as the teams head to Houston to finish the series at Minute Maid Park.

As for the pitch that was called a ball by umpire Laz Diaz, the strike zone box on TV said it was a strike. This video indicates it was not outside, and Eovaldi was so sure it was a strike that he headed toward the dugout. And many post-game analysts were of the same opinion. Below is a schematic of the six pitches to Castro, the green dots being the pitches that were called balls. Both were actually strikes, but Pitch 4 stood out because it would have been strike three to end the inning. Pitch 5 was fouled off and Pitch 6 knocked in the go-ahead run.

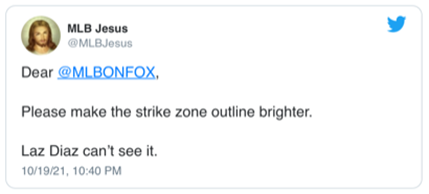

Twitter heated up and many sportswriters bemoaned how a mistaken judgment call on a ball/strike had changed the course of the game. This will no doubt be fodder for the movement to switch to robot umpires for ball/strike calls. A similar issue occurred in Game 5 of the NLDS when the Dodgers/Giants game ended on a bad judgment call of a checked swing. Tough week for umpires.

MLB Jesus tweeted a novel idea about how the TV coverage could be used to help umpire Laz Diaz on balls and strikes.

50 Years Ago (1971) – Pirates v. Orioles: In 1969, each league was divided into two six-team divisions, setting up a first round of best-of-five playoffs between the division winners in each league (ALCS and NLCS).

In 1971, the winners of the NLCS and ALCS were Pittsburgh and Baltimore, setting up a World Series between two of the best teams of the era. The Orioles, behind the likes of Brooks Robinson and Frank Robinson, won three straight AL pennants from 1969 to 1971. They were the defending World Champions after beating Cincinnati in the 1970 Series. The Pirates won the NL East six times in the 1970s.

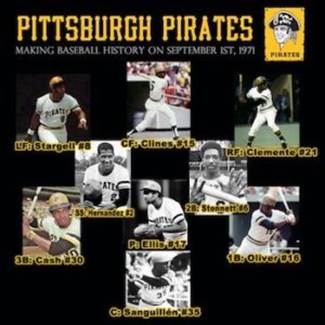

In another highlight of the 1971 season, the Pirates made baseball history on September 1 by fielding an all-Black and Latino lineup (below).

In the Series, the evenly matched teams split the first six games. The fourth game, played in Pittsburgh, was the first night game in World Series history. Now all are night games (a/k/a prime time).

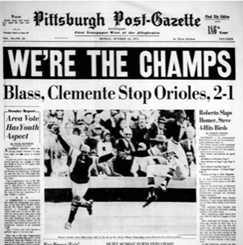

The seventh game was in Baltimore and was a pitching duel between the Orioles’ Mike Cuellar and the Pirates’ Steve Blass. The two had squared off in Game 3 when Blass pitched a 5-1 complete game victory. Blass repeated in Game 7 by again allowing only one run in a complete game. With a homer by Roberto Clemente providing the margin, the Pirates won the game 2-1 and the Series 4-3.

Blass was the pitching star for the winning Pirates – two complete games and a 1.00 ERA. The batting star and Series MVP was 37-year-old Roberto Clemente. The “Great One” had 12 hits in 29 at bats, an average of .414. His 12 hits included 2 doubles, 1 triple and 2 home runs. He got a hit in each of the seven games, just like he had done in the 1960 Series when the Pirates beat the Yankees on Bill Mazeroski’s walk-off homer.

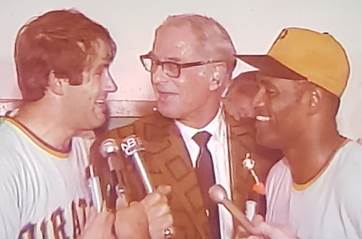

Below, after Game 7, Steve Blass, broadcaster Bob Prince and Roberto Clemente. Video here.

The Pirates followed up with a good year in 1972, finishing with the best record in the National League. World Series pitching star Steve Blass (19-8) was the runner-up for the Cy Young Award. Slowed by injuries, Roberto Clemente played in only 102 games, but he hit .312 and in his last game of the regular season got career hit #3,000.

But that was the end of good news for 1972. The Pirates lost the NLCS to Cincinnati – so no World Series berth. On New Year’s Eve, Roberto Clemente died in an airplane crash while on an earthquake relief mission to Nicaragua. At the memorial service in Clemente’s homeland of Puerto Rico, Steve Blass gave a moving eulogy, concluding with…

Let this be a silent token

Of lasting friendship’s gleam

And all that we’ve left unspoken—

Your friends on the Pirate team.

The next season, Blass lost his touch on the pitching mound. He retired in 1974.

[Royals Trivia: Roberto Clemente got hit #3,000 on September 30, 1972. Exactly 20 years later (9/30/92), George Brett got his 3,000th hit. And then George got picked off first base (video here).]

Roger Angell on the 1971 World Series: Roger Angell, the legendary baseball essayist, is now 101 years old. In October of 1971, Angell penned a New Yorker essay about the World Series. Some quotes:

[The 1971 World Series was] “a shared experience, already permanently fixed in memory, of Roberto Clemente playing a kind of baseball that none of us had seen before – throwing and running and hitting at something close to the absolute perfection, playing to win but also playing the game as if it were a form of punishment for everyone else on the field. He is a frightening batter…a pitch…in his power zone is in imminent danger of departure.”

“[Clemente] carrying his bat up to the plate like a surveyor setting up his transit, he precisely measured out a low single, a high drive that was caught, and a long, beautiful geodetic line straight to the foot of the right field barrier.”

On Steve Blass, “…a right-hander, standing almost primly on the right-hand first-base corner of the mound, and throwing with a quick pump and a double flurry of legs and elbows ending in an unstylish little stagger.”

In 1975, Angell wrote a New Yorker essay on Steve Blass who had retired from baseball. The article starts with a look back at the iconic photo showing Blass and catcher Manny Sanguillen celebrating the Pirates winning the 1971 World Series:

Here is Angell’s take on the photo:

“The photograph shows a perfectly arrested moment of joy…the catcher is running toward the camera at full speed, with his upraised arms spread wide. His body is tilting toward the center of the picture, his mask is held in his right hand, his big glove is still on his left hand, and his mouth is open in a gigantic shout of pleasure…the pitcher is just past the apex of an astonishing leap… two of the outreaching hands have overlapped so that the pitcher’s bare right palm and fingers are silhouetted against the catcher’s glove…There is a further marvel – a touch of pure fortune – in the background, where a spectator in dark glasses…is lifting his arms in triumph…and it binds and recapitulates the lines of force and the movements of the theme of the composition as serene and well-ordered as a Giotto. The subject of course, is classical – the celebration of the last out of the seventh game of the World Series.”

Leave it to Roger Angell to connect the classic photo to a Renaissance painter. The copy desks around the country also loved the photo, starting with the hometown paper:

My law partner Tim Sear has an original clipping of the page shown above. He would have been 13 at the time, growing up in Iowa with a father who was a big fan of the Pirates. A family friend sent the clipping from Pittsburgh, and to this day is part of Tim’s “Pirates Archives.”

Some others…

The photographer was Rusty Kennedy of the Associated Press. According to a recent excellent article by Joe Capozzi, Kennedy took the photo from a platform behind the centerfield fence, some 400 feet away. This was before cameras had auto-focus, and as he looked through his long-range lens, he saw that Blass looked fuzzy. He quicky manually focused and clicked. The players were actually celebrating about 35 feet apart, but the distance and angle of the shot combined for the famous result.

The photo was hung on the walls of hundreds of taverns, offices and dens in Greater Pittsburgh, alongside the photo of Bill Mazeroski hitting his walk-off homer in the 1960 World Series.

Roberto Clemente Award: Major League Baseball presents the annual “Roberto Clemente Award” to the player who “best exemplifies the game of baseball, sportsmanship, community involvement and the individual’s contribution to the team.” Each team nominates a player, and the winner is announced at the World Series.

The Royals nominee for 2021 is Salvy Perez, and like all of his fellow nominees, Salvy wore Clemente’s #21 on September 15, the first day of Hispanic Heritage Month. MLB announced that this date will be celebrated as Roberto Clemente Day in perpetuity. Salvy responded by hitting home run #44, circling the bases in his #21 jersey. Video here.

When Salvy hit his home run wearing #21, I emailed a heads-up to Tim Sear. Tim’s response: “What a rare treat it is to have picked Clemente as my hero more than 50 years ago—when I knew him only as a player—and through all these years—and all the examinations of his life—he only stands taller as a hero not just for his sports career—but for how he lived his life.”

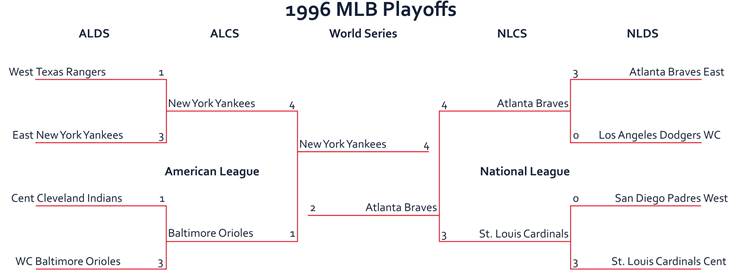

25 Years Ago (1996) – Yankees v. Braves: By 1996, the post-season playoffs included an extra round of games structured on a 3-division/wild-card format. It played out like this:

The year would prove to be the start of a new Yankee dynasty. Starting in the 1920s, the Yankees won at least five AL pennants in each decade through the 1960s. They slowed slightly in the 1970s, winning only three (1976, 1977 and 1978, each time beating the Royals in the ALCS). They won the AL pennant in 1981, but lost the Series to the Dodgers. The Yankees then hit a dry spell for 15 years, their longest drought since 1920.

But they are the Yankees. They again became dominant, winning six pennants in eight years from 1996 to 2003 – four of those ending in World Series victories. The new core was on the rise in 1996 – rookie shortstop Derek Jeter, second-year starting pitcher Andy Pettitte, and second-year setup reliever Mariano Rivera. Pettitte and Rivera finished second and third in Cy Young voting and Jeter was rookie-of-the-year.

The Atlanta Braves were likewise dominant in the NL, winning five pennants in the 1990s. The key for the Braves was a trio of Hall of Fame starting pitchers: Tom Glavine, Greg Maddux and John Smoltz. From 1991 to 1998, they combined to win seven Cy Young Awards.

So lots of Cy Young talent on both teams. And the hero of the 1996 World Series was indeed a pitcher. But not one who received any Cy Young votes. Here’s what happened.

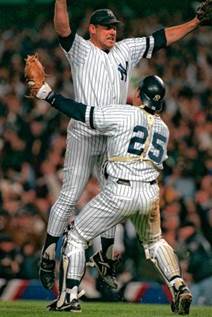

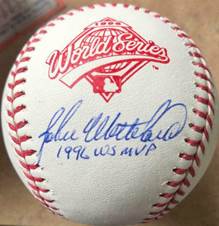

After the Braves won the first two games, the Yankees won the next four to win the Series. All of the Yankee wins were close (5-2, 8-6, 1-0 and 3-2). The same Yankee pitcher finished each game for the save – John Wetteland (below, celebrating the Series victory with catcher Joe Girardi). The MVP of the 1996 World Series: John Wetteland.

Wetteland had played five seasons with the Dodgers and Montreal before moving to the Yankees in 1995. In 1996, he led the AL with 46 saves. But his time with the Yankees was closing out. Budding star Mariano Rivera was set to take over the closer role, and Wetteland became a free agent. He signed with Texas and finished out a 12-year MLB career with 330 saves (for some perspective, Dan Quisenberry had 244). In a sad turn of events, Wetteland is scheduled to go to trial in January of 2022 on child sexual abuse charges. Most articles on the criminal case reference his 1996 World Series MVP award.

Lonnie’s Jukebox – 1971 World Series Edition: The year of 1971 was good for the Pirates, and it was also good for rock ‘n’ roll fans. It was a rich year in music, and to give you an idea, click here to see the Top 100 songs of the year. The music from 1971 is currently being celebrated in a 8-episode series on Apple TV+ (trailer here). Click on the song titles below to listen to the jukebox.

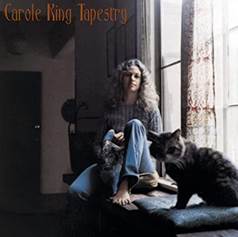

Among the #1 songs that year were three written by Carole King: “It’s Too Late” (sung by Carole), “Go Away Little Girl” (Donny Osmond) and “You’ve Got a Friend” (James Taylor). “Go Away Little Girl” was co-written with Gerry Goffin and was also a #1 hit by Steve Lawrence in 1963. “It’s Too Late” was one of the singles released from Carole’s megahit album Tapestry.

Among other big albums that year: Marvin Gaye – What’s Going On; Joni Mitchell – Blue; The Rolling Stones – Sticky Fingers; and John Lennon – Imagine.

“Me And Bobby McGee” by Janis Joplin. A posthumous hit, recorded days before her death in October of 1970.

“Signs” by Five Man Electrical Band. As part of our Covid world, many businesses are having trouble finding enough employees. Rita saw a tweet of a sign being used by one desperate business: “The employee shortage is so bad that long-haired freaky people can now apply.” This was a reference to the 1971 song “Signs,” which opens with these lyrics…

And the sign said

“Long-haired freaky people

Need not apply”

So I tucked my hair up under my hat

And I went in to ask him why

“Joy to the World” by Three Dog Night. This record plays over the end credits in the baby boomer movie The Big Chill (1983). But what I most remember about the song is that it also starts the movie with a kid singing the opening lines…”Jeremiah was a bullfrog/Was a good friend of mine.” The scene then transitions into the opening credits that include the cast plus clips of preparing a body for a funeral, all set to Marvin Gaye’s “I Heard it Through the Grapevine” (video here). [Movie Trivia: The body being prepared for the funeral is that of a then unknown Kevin Costner. His face is not seen in the opening clip, and the flashback scene with him was cut from the movie.]

“Maggie May” by Rod Stewart.

“Family Affair” by Sly & The Family Stone.