This is my 20th annual message for Martin Luther King Jr. Day. The first, in 2002, was an internal email to the lawyers and staff at the Polsinelli law firm. We had added the MLK holiday at the firm, and I sent out King’s “Letter From a Birmingham Jail” as a reminder of why we celebrate the holiday. The annual message has grown in length and circulation over the years, and since 2016, it has been merged into my Hot Stove posts. All of the prior MLK messages are at this link on the Lonnie’s Jukebox website.

This year, I am revisiting one of my prior themes. Martin Luther King’s last speech, “I’ve Been To the Mountaintop.” But I’m adding a new player, Buck O’Neil, for a journey from Mount Nebo to Memphis to Cooperstown.

Moses on Mount Nebo: In 2009, Rita and I traveled to Jordan to see the archeological wonders of Petra. On our return to Amman, we stopped at Mount Nebo where Moses is said to have stood to view the Promised Land. Although Moses had led the Israelites across the desert to this point, he was not allowed by God to continue with them to the Promised Land. Joshua would lead them the rest of the way. Below, the Promised Land as seen from Mount Nebo.

Martin Luther King in Memphis: Fast forward from biblical times to April 3, 1968. Martin Luther King was in Memphis to support striking sanitation workers. That night, he gave what would be his last speech: “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop.” King prophetically spoke of his likely early death and that he would not get to see the full fruits of his labor in the Civil Rights Movement. “I would like to live a long life; longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will. And He’s allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I’ve looked over. And I’ve seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land.” The next night, Martin Luther King was assassinated.

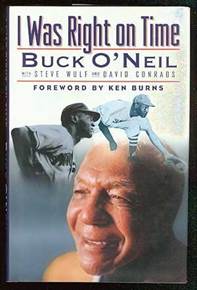

Buck O’Neil – “I Have a Dream”: I don’t know that Buck O’Neil ever phrased it this way, but he had a dream – that people would know about and appreciate the Negro Leagues. In his 1996 autobiography (I Was Right on Time), Buck made this Moses-like statement:

“I have another reason for sticking around: Sometimes I think the Lord has kept me on this earth as long as He has so I can bear witness to the Negro Leagues.”

Buck’s approach was simple. Tell the stories of the players and the games. And he was a storyteller of legend.

After Buck ended his playing and managerial career for the Kansas City Monarchs in 1955, he became a scout and then a coach for the Chicago Cubs. In 1988, he retired so he could be home more with his wife Ora in Kansas City. The Royals came calling and he began scouting for them. All along the way, Buck told his stories.

In 1990, he reached an important milestone for his dream. He was one of the co-founders of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City. This gave him an expanded forum for telling his stories.

In 1994, Buck took his stories to the national stage. His “I Have a Dream” moment was not an iconic speech, but he succeeded in reaching and charming millions of people. During a series of appearances in Ken Burns’ PBS documentary series Baseball, Buck’s personality and storytelling captivated the viewers. He became a national celebrity. At the age of 82.

Ken Burns: “After the documentary was first broadcast in 1994, and Buck became known to a national television audience, he told me he felt lucky to get the attention because he said, ‘I’ve been sayin’ these things for 60 years – and now people are listening.’ I told him we were the lucky ones, for having the chance to listen to him.” Below, Buck and Ken in their Monarchs uniforms.

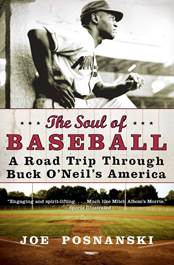

“The Promised Land” – Baseball Hall of Fame: A big target for Buck’s “witnessing” for the Negro Leagues was the Hall of Fame in Cooperstown. In Joe Posnanski’s road-trip book about Buck (The Soul of Baseball), Buck lamented that the HOF process was so slow that most Negro Leaguers were inducted posthumously. From Joe’s book:

“The Hall of Fame meant even more to those great Negro League Players who never got a chance to play in the Major Leagues. Buck said to them the Hall of Fame meant redemption. A Hall of Fame induction was their chance to hear at last after all the years that they were great. They belonged in the gallery with Babe Ruth and Stan Musial, Sandy Koufax and Walter Johnson. To those few Negro League players elected to the Hall of Fame, it was bigger than immortality. It was an apology.”

For decades, admission to the HOF was denied to Negro League players. After a nudge from Ted Williams, the Hall of Fame set up a Negro Leagues Committee that led to the induction of nine Negro League players from 1971 to 1977. For the next 17 years (1978-1994), Negro Leaguers were eligible via the Veterans Committee, but only two were elected.

Buck O’Neil joined the Veterans Committee in 1981 and was not happy with the pace. So he argued that at least one Negro Leaguer should be elected each year. He said in his book that is was ironic that he was arguing for a segregated category, but he wanted better results. The committee agreed to start that process in 1995, quite possibly influenced by Buck’s celebrated appearance in Ken Burns’ 1994 documentary. Under Buck’s plan, seven Negro League inductees were added from 1995 to 2001.

It was still too slow. MLB stepped in with a grant to the HOF for an extensive study of Black baseball. This led to a special committee that considered a pool of 94 players and executives. This was narrowed down to 39 for the ballot. Buck O’Neil was not on the committee – he was on the ballot. The committee met on February 27, 2006, and elected 17 new members to the Hall of Fame. But not Buck. The reaction from the public and the press was virtually unanimous. Buck was robbed!

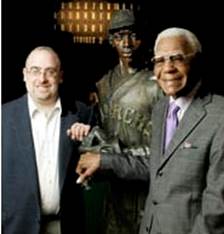

There was one notable exception to the outrage. Buck O’Neil. To tell that part of this story, I turn to Joe Posnanski who was with Buck when the news came in (below, Joe and Buck on the Field of Legends at the NLBM).

Joe has written many times about that day, and the excerpts below are from a 2016 article (see full article here).

“I will always remember the moment Buck found out that he was not elected. I will always remember the way his head dropped, ever so slightly, before he quickly (too quickly) said: ‘Well, that’s the way the cookie crumbles!’

I will always remember how moments later, he turned to me and asked: ‘Who do you think will speak for the 17 who were elected?’ I was so angry for him, so hurt for him, I barely understood the question. Who would speak? Who cares?

‘I wonder if they’ll ask me to speak,’ he said. I looked at him with a new sort of awe. He had already recovered from the shock. He was disappointed — I know he was disappointed — but it had taken only a few minutes for him to find his equilibrium. Buck’s life was full of potential disappointments. He did not get a chance to play in the Major Leagues. He did not get a chance to manage in the Major Leagues, and I think he would have loved that. He was mocked at times, ignored for many years, and then in the last months of his life he was told that the Committee didn’t find him quite Hall of Fame worthy.

But he didn’t see any of those things as disappointments because he embraced the joys of life. He didn’t play in the Major Leagues, but he got to play with some of the greatest players in the world. He didn’t get to manage in the Major Leagues, but he managed Ernie Banks, Satchel Paige, Hilton Smith, Elston Howard and so many others. He also heard a kid named Charlie Parker play saxophone before anyone had ever heard of him. He had dinners with Lionel Hampton and Ella Fitzgerald and Count Basie and Jesse Owens and Joe Louis. He told stories to David Letterman, sang for Ken Burns and was put into the Stephen Colbert Hall of Fame.

‘Would you really speak at the Hall of Fame?’ I asked him — remember this was mere moments after he found out that he was not elected.

‘Son’ he said, ‘what is my life about?’”

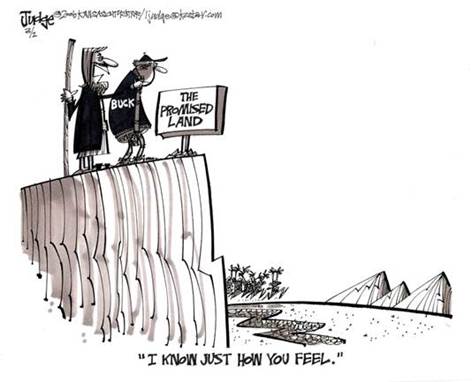

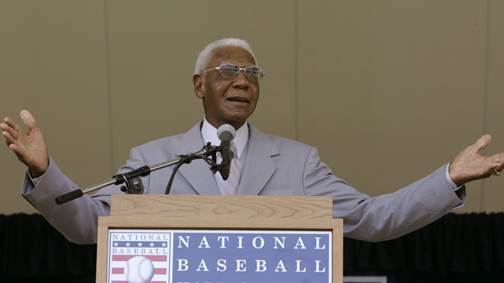

Buck O’Neil in Cooperstown – “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop”: Buck was indeed asked to speak for the 17 inductees (all were deceased). So Buck went to the mountaintop (the podium for the induction ceremony) to witness and testify for the 17 honorees who were entering the Promised Land (the plaque room of the Hall of Fame). Lee Judge, political cartoonist for the Kansas City Star, aptly compared Buck to Moses on Mount Nebo.

Buck was of course the star of the show at the induction ceremony held on July 30, 2006. He talked of the importance of the Negro Leagues to the community – the third largest Black business in the country at the time (after insurance and cosmetology). As for the 17 players and executives being inducted, Buck said…

“Next, Negro League baseball. All you needed was a bus, and we rode in some of the best buses money could buy, yeah, a couple of sets of uniforms. You could have 20 of the best athletes that ever lived. And that’s who we are representing here today. It was outstanding…That was Negro League baseball. And I’m proud to have been a Negro league ball player. Yeah, yeah….I’d rather be right here, right now, representing these people that helped build a bridge across the chasm of prejudice…This is quite an honor for me.”

Buck then spoke on one of his signature themes. Although he had suffered disappointments, many because of racism, he was never bitter. “I never learned to hate.”

But love, oh yes. Buck believed in the kind of love embraced by Martin Luther King – the concept of “agape.” Buck explained this Greek term of philosophy to the Hall of Fame crowd:

“So, I want you to light this valley up this afternoon. Martin said “agape” is understanding, creative — a redemptive good will toward all men. Agape is an overflowing love which seeks nothing in return. And when you reach love on this level, you love all men, not because you like ’em, not because their ways appeal to you, but you love them because God loved them. And I love Jehovah my God with all my heart, with all my soul, and I love every one of you — as I love myself.”

He concluded the event in Buck O’Neil style, asking the crowd to join hands and sing along with him…

The greatest thing in all of my life is loving you.

The greatest thing in all of my life is loving you

The greatest thing in all of my life is loving you.

The greatest thing in all of my life is loving you

[See the video of Buck’s speech here (7:24).]

Just over two months later, on October 6, 2006, Buck O’Neil died. He was 94.

Next Monday on the MLK holiday, please reflect on the legacy of Martin Luther King and give a nod to his fellow hero on the mountaintop, Buck O’Neil, the Soul of Baseball.

Lonnie’s Jukebox (1) – Buck O’Neil Sings: Royals fans are familiar with Buck’s singing voice from his ads for the team. The same song is also played on his bobble-head. Click on “Take Me Out to the Ballgame” and find yourself smiling.

Lonnie’s Jukebox (2) – Bob Kendrick – The Joshua Generation: When Moses was not allowed to enter the Promised Land, Joshua led the rest of the way. When Barack Obama gave his Selma speech in 2007, he spoke of standing on the shoulders of the Moses Generation of the Civil Rights Movement (MLK, John Lewis and others). But the battle for social justice was not over, and the Joshua Generation would need to continue the cause.

The Moses Generation of the Negro Leagues (Buck, Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson, etc.) have passed on. But a Joshua Generation is in place. A timely example of this is that Major League Baseball recently agreed that the statistics of the Negro Leagues will now be part of the MLB record book (a key part of the Promised Land). This would not have happened without the dedicated work of many authors, archivists, researchers and statisticians. Kudos to Ray Doswell, Phil Dixon, Larry Lester, Pete Gorton and others from this Joshua Generation.

Another fine example of the Joshua Generation is Bob Kendrick, President of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum. There are countless ways he has expanded the reach of the museum, but I’m going to focus on the one that honors the legacy of Buck O’Neil – Bob’s storytelling. I’m sure that most readers of Hot Stove have seen Bob on local and national television. He always provides a joyous account of the Negro Leagues, delightfully sprinkled with anecdotes. He also sells the beauty of baseball – encouraging kids and fans to enjoy the game of today. (Rita says whatever Bob is selling, she’s buying). He is also the best-dressed man in and out of baseball (always “dressed to the nines”).

Over the past 22 weeks, Bob has been releasing vignettes (3 to 5 minutes each) to recount Black America’s journey toward equality through the game of baseball. The 22 chapters of “Storied” are available here. Buck is Chapter 10. Storytelling at its best.

Below, Bob on the Field of Legends. Yes, that’s a golf club in his hands. Bob often joined Buck for a round and, as you might guess, has a story about that. It was the last round of golf in Buck’s life. Playing at Wolf Creek, on the same tees as the rest of the foursome, Buck shot 94…at age 94. Buck joked “Well, fellas, I shoot my age. But that ain’t a good score anymore.”

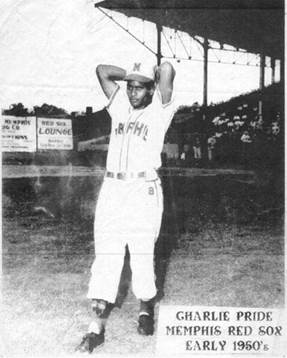

Lonnie’s Jukebox (3) – Charley Pride (RIP): In 1953, the Kansas City Monarchs were managed by Buck O’Neil. On another Negro League team, the Memphis Red Sox, there was a rookie pitcher named Charley Pride. Fifty-three years later, on July 30, 2006, they were on the same stage at the Baseball Hall of Fame. Charley to sing and Buck to make the induction speech. Like Buck, Charley was chronicled by Ken Burns – in the 2019 PBS documentary series Country Music.

Charley Pride’s career path was indeed unique. When he was 13 years old in 1947, Jackie Robinson broke the color line. This gave Charley hope that he could escape his cotton-picking world. He became a good pitcher and began his career with the Memphis Red Sox in 1953. Over the next five years, he played on various Negro League and minor league teams. But a sore arm forced him to change course and take up his second passion, country music.

How did that go? Charley Pride became a trailblazing Jackie Robinson of country music. He was the first Black artist with a #1 country record. He had 52 top-10 country hits, 30 of which made it to #1. He was the first artist of any race to win the Country Music Association’s male vocalist award two years in a row. In 2000, he was inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame.

Charley Pride died last month of complications of COVID-19. He was 86.

Pride never forgot his baseball roots. He was a part-owner of the Texas Rangers and sometimes took the field during spring training. He was also a good friend of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum. He attended many events, including several years at the Buck O’Neil Golf Classic. Below, at the 2013 Classic, he picked up Rick Sutcliff’s guitar and turned the awards banquet into a concert. Bob Kendrick is enjoying the show.

I’m not well versed in country music, but here are a couple of good jukebox selections…

“Kiss an Angel Good Morning” – Charley Pride’s biggest hit. Watch out, it will be an earworm that sticks with you for a while.

“Mountain of Love” – I picked this one because it covers two of the subjects in this Hot Stove post. Mountain (top) and love (Buck). I’m familiar with the song because it was a hit by Johnny Rivers in 1964 (#9 on the pop chart). It was a #1 country hit for Charley Pride in 1982.

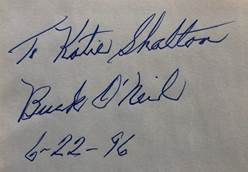

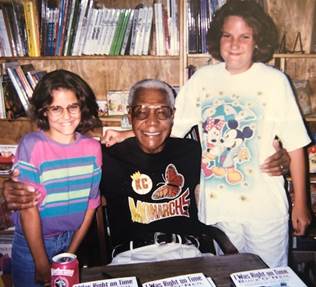

A Personal Note: My copy of Buck’s book belonged to my mother. She was a big baseball fan and adored Buck O’Neil. They both died in 2006, mom at 85 and Buck at 94.

Inside the book…

At the book signing, Buck gave it up for mom’s great-granddaughters (my granddaughters) Carly (10) and Alex (12). Their dad is Brian, the webmaster of the Lonnie’s Jukebox website. The girls (women) now have their own children as tall as Carly was then (making Brian a grandfather).

Thank you Buck.