And now there are two. The World Series starts tomorrow night.

Representing the American League is Houston, the team that had the best record in baseball this year. In the National League, the pennant was won by a wild-card team, the Washington Nationals. The Astros won the Series two years ago. The Nationals franchise started as the Montreal Expos in 1969, moved to DC in 2005, and before this year, had never been in a World Series.

At first glance, the Astros would appear to be the heavy favorite. Their season record was 107-55, while the Nats were 93-69, a deficit of 14 games. But the differential came in the early part of the season. Here is the split at the 50-game mark:

First 50 Games: Nationals (19-31). Astros (33-17).

Final 112 Games: Nationals (74-38). Astros (74-38).

After their sluggish start, the Nationals were the equal of the Astros for the rest of the regular season. They have continued to play well, winning the wild-card game, beating the 106-win Dodgers in the NLDS and sweeping the Cardinals in the NLCS. They have had eight straight winning seasons, making the playoffs in five of them. The Nationals also have the support of the baby sharks (see Lonnie’s Jukebox at the end).

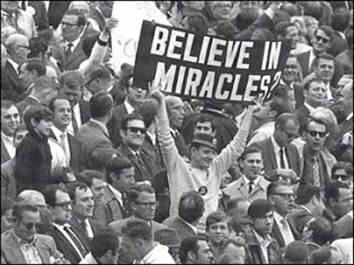

So it will not take a miracle for the Nationals to win their first World Series. Which leads me to the World Series of 50 years ago…

1969 – The Miracle Mets: There was no shortage of big events in 1969. In January, the New York Jets led by Joe Namath shocked the football world by winning the Super Bowl. In July, the first man walked on the Moon. In August, some 400,000 people gathered at Woodstock. In October, the New York Mets won the World Series. In November, some 500,000 people marched in Washington to protest the Vietnam War.

But only one of these events was widely referred to as a miracle – suggesting a result not explicable by natural or scientific laws. The Miracle Mets.

Why was the result so improbable? Well, in the first seven years of their existence, the team finished 9th or 10th in the 10-team National League. Then in their eighth year they won the World Series. They had gone from 40 wins in 1962 to 100 wins in 1969. For the fans and the media, this felt like a miracle.

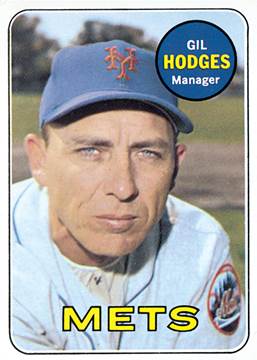

But according to author Wayne Coffey, the Mets players and officials do not agree about the “M-Word.” Manager Gil Hodges said “There’s nothing miraculous about us.” The Mets of 1969 believe that it was smart drafting, key trades, teamwork and Hodges’ leadership rather than divine intervention as suggested by dubbing them the Miracle Mets.

To sort this out, I checked out some history. Several books have been published in this 50th-annivsary year to reminisce about the team, and I chose Wayne Coffey’s They Said It Couldn’t Be Done. I also reached back to a book published soon after the 1969 Series, Joy in Mudville, by sportswriter George Vecsey who covered the Mets for Newsday and the New York Times during the 1960s.

The Case for a “Miracle”: I can see why the fans and the media felt like something extraordinary had happened. Having been deserted by the Dodgers and Giants who fled to California in 1958, their new team was created by expansion in 1962. What followed was a horrible seven years on the playing field. Then they won it all in their eighth season, and there was understandable euphoria. A good example is recounted by George Vecsey in the opening paragraph of Joy in Mudville,

“They spilled over the barricades like extras in a Genghis Khan movie, all hot-eyed and eager for plunder. The Mets had just won the 1969 World Series, and the fans wanted to take home a talisman piece of Shea Stadium, to secure good fortune for the rest of their lives. For half an hour they sacked the stadium, clawing at home plate with their fingernails, ripping out great chunks of sod for souvenirs…There had always been something mythical about Met fans, the way they kept the faith.”

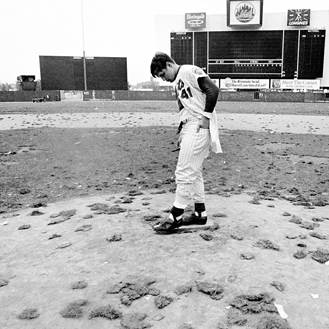

One fan charging the field that day was Wayne Coffey, then a 15-year-old attending the game with his grandfather. When the last out was made, he first watched as the “happy hordes” headed to the field where they “reveled, ransacked, pillaged, plundered.” He could not resist, saying “I’m going to go out there, Gramps” (who said “be careful”). Coffey pulled up a three-inch-square chunk of world-championship turf that became a treasured piece of sod in the family backyard. Below, Tom Seaver checking out the vandalized field.

To fully appreciate the case for a miracle, we need to look at it through the eyes of those who witnessed the first seven years of the Mets. It all started with a lousy expansion draft.

Baseball Expansion: The American League expanded from eight to ten teams in 1961, and the National League followed suit in 1962. The new NL teams were the New York Mets and the Houston Colt .45s (who became the Astros when they moved to the Astrodome in 1965). The Mets and Colt .45s drafted players from the existing NL teams, but the other owners had selfishly protected most true major leaguers from the draft. This left mostly (i) unproven young players and (ii) veterans in the twilight of their careers.

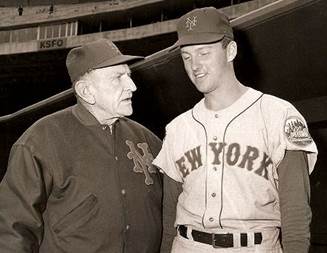

The Mets felt the best way to draw fans was to stock up on veterans, especially those well known to the former Dodgers and Giants fans. The Mets also used that approach when they named Casey Stengel as the manager. Casey was available because he had been fired by the Yankees after the 1960 World Series loss on Bill Mazeroski’s walk-off homer. Casey was a perfect choice – he was a beloved character in New York and could distract the fans from the dreadful baseball they were likely going to see. It worked like a charm.

As for what was to be put on the playing field, Casey said of the expansion draft, “I want to thank all those generous owners for giving us those great players they did not want.”

1962 – The “Amazin’ Mets” (40-120): The inaugural year was awful on the playing field (the Polo Grounds for the home games). The Mets went 40-120, finishing 60.5 games behind the pennant-winning Giants (who just five years before had called the Polo Grounds home).

But the fans did not mind. National League ball had returned to New York. The likes of Willie Mays and Hank Aaron came to play against the Mets. The Mets roster included some fading Dodger stars, the most notable being first baseman Gil Hodges. He was one of the fabled “Boys of Summer” and had knocked in both runs in the 2-0 victory that wrapped up the 1955 World Series, the only Series the Dodgers won during their decades in Brooklyn.

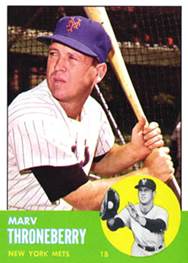

The Mets were aware that the 38-year-old Hodges would need backup and so acquired Marv Throneberry from Baltimore. Marv started his major league career with the Yankees where he mostly rode the bench from 1955 to 1959 under manager Casey Stengel. Then, as colorfully recounted by George Vecsey in Joy in Mudville, “In 1960, he was dispatched on the underground railroad to Kansas City, the elephant boneyard of the Yankee farm system. Later he washed up in Baltimore.” As a former KC A’s fan, I well remember the pain of the “elephant boneyard.”

Throneberry called himself “Marvelous Marv,” a moniker not indicative of his skills as a batter, fielder or baserunner. Throneberry took over first base on a regular basis after Hodges was out for the season with kidney stones. Marv’s less than stellar play often made him the face of the hapless Mets, but he also became something of a folk hero. So many entertaining things happened around Marvelous Marv that he gets a whole chapter in Vecsey’s book.

I’ll finish 1962 with two quotes from Casey Stengel, always the master of misdirection and humor to keep the press and fans happy.

Casey enjoyed referring to his team as the “Amazin’ Mets.” An example: “Come see my Amazin’ Mets. I’ve been in this game a hundred years, but I see new ways to lose I never knew existed before.” He used the term so much that it became a common way for the fans and the media to refer to the team.

Casey also famously said “Can’t anybody here play this game,” and that became the title of Jimmy Breslin’s book about the 1962 Mets. To give a flavor, Bill Veeck quipped in his introduction that Breslin succeeds in “preserving for all time a remarkable tale of ineptitude, mediocrity, and abject failure.” But the book, just like the fans and the media, found them to be a lovable bunch of losers.

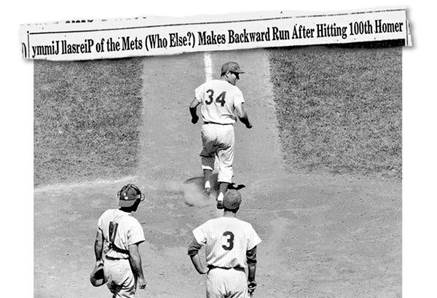

1963 (51-111): Another 10th place finish. The aging Gil Hodges returned for another season, but was “traded” in May to the Washington Senators who signed him as their manager. In return, Washington sent outfielder Jimmy Piersall to the Mets. Piersall was well known to fans for his 1955 book (and adapted movie) Fear Strikes Out, depicting his struggle with bipolar disorder. After joining the Mets, he hit his 100th major league homer and proceeded to round the bases while running backwards. His hitting was otherwise anemic and he was released in July. But we will always have this photo and the clever headline.

1964 (53-109): The Mets relocated to the new Shea Stadium, but it did not move them up in the standings. Casey said that the Mets came in 30th in 1964, reflecting that they had finished 10th for three straight seasons.

But fans swarmed to the new stadium for a season attendance of 1,732,597. The Yankees won the AL pennant and drew 1,305,638. The Mets continued to outdraw the Yankees for the next 11 years.

A new pitcher on the roster was Kansas City native Bill Wakefield (“the bright Stanford boy who replaced Bearnarth as the ace of the bullpen” per George Vecsey). Wakefield appeared in 62 games for the Mets in what would be his only major league season. He started a few games, including the first night game at Shea (he lost). Small world story: The first major league night game was in Cincinnati in 1935. The losing pitcher that night was the Reds Joe Bowman – Wakefield’s next door neighbor when Wake was growing up in Kansas City.

On May 31, the Mets and Giants played a Sunday doubleheader at Shea before a crowd of 57,037, the biggest MLB crowd of the season. The Giants won both games, the first taking 9 innings (time of game, 2:29) and the second, 23 innings (time of game, 7:23). Almost ten hours of baseball.

Bill Wakefield started the second game for the Mets, but he pitched only 2 innings of the 23. With a rally going in the bottom of the second, Casey pulled Wakefield for a pinch hitter. As Wake tells the story, he asked Casey why the quick hook and was told “Because you can’t hit and you’re not getting them out.” As the extra-inning game got deeper into the night, a tired Casey spotted Wakefield on the bench and told him to head to the bullpen to loosen up. He had to tell Casey he had already pitched, and then to make it easier for the manager, Wake went up to the stands to watch the rest of the game.

1965 (50-112): Last place for the fourth year. Or in Casey parlance, 40th place.

A new coach arrived to supplement the humor and tortured syntax that endeared the fans to Casey. It was Yogi Berra, the man behind the plate during all of Casey’s 12 years managing the Yankees. Yogi had been the Yankees manager in 1964, but was fired after the Yankees lost to the Cardinals in the World Series. The same thing that had happened to Casey after the Yankees lost the 1960 Series. Or as Yogi might say, déjà vu all over again.

On July 30, Casey fell and broke his hip while celebrating his 75th birthday at Toots Shor’s in Manhattan. He decided not to return, and the managing duties were turned over to Wes Westrum.

1966 (66-95): The Mets finally escaped the cellar. They came in 9th, beating out the Chicago Cubs. In an odd turn, they finished higher than the Yankees who slipped to 10th in the AL.

This was also the season of some rare serendipity for the Mets. The team signed Tom Seaver even though they had not drafted him. Seaver played college ball at USC. In 1966, he was drafted by Atlanta and signed a contract. But USC had already played two exhibition games, and under MLB rules, there could be no signing during a current college season. The contract was voided, and Seaver decided to continue at USC. But then the NCAA ruled him ineligible because he had signed a pro contract. He had nowhere to play, and his father threatened a lawsuit. This prompted the league to let any team, other than Atlanta, match the Atlanta offer. Three put in a bid, and the lottery drawing awarded Seaver to the Mets. Akin to a miracle.

1967 (61-101): The Mets returned to last place.

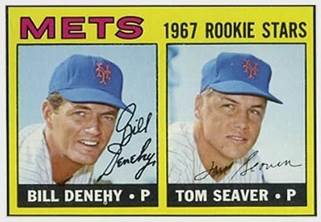

Tom Seaver was rookie of the year, proving he was indeed a star as reflected on his Topps baseball card.

The other pitcher on the card also played a major role in the future of the Mets. Bill Denehy was traded after the 1967 season to the Washington Senators. In exchange, the Senators agreed to release manager Gil Hodges so he could sign with the Mets. It was a reverse of the trade made by the teams in 1963 when the Senators hired Hodges as manager and gave the Mets Jimmy Piersall in return. Denehy played mostly in the minors before ending his playing career in 1973. But his rookie card remains valuable in the marketplace.

1968 (73-89): Manager Gil Hodges led the Mets to their best season to date, but still only good enough for 9th place, just one game ahead of the last place Astros.

The Case for “Not a Miracle”: In hindsight, the Mets roster was not an overnight success, i.e., not a miracle. The development had been methodical (other than Seaver, which was blind luck). There were three general managers from 1962 to 1969: George Weiss (1962-1966), Bing Devine (1967) and John Murphy (1968-1969). Here is how they obtained the key players for the 1969 roster.

Amateur free agents – 1962: Ed Kranepool; 1963: Ron Swoboda, Cleon Jones and Bud Harrelson; 1964: Jerry Koosman and Tug McGraw.

MLB Drafts (Instituted in 1965) – 1965: Ken Boswell and Nolan Ryan; 1966: Tom Seaver (indirectly); 1967: Gary Gentry and Rod Gaspar; 1968: Wayne Garrett.

Trades – 1966: Jerry Grote from Houston; 1967: Ed Charles from the Kansas City A’s; 1968: Tommy Agee and Al Weis from the White Sox and Art Shamsky from Cincinnati; 1969 in mid-season: Donn Clendenon from Montreal.

1969 (100-62): Everything clicked. The players astutely assembled by the Mets came together under manager Gil Hodges to win 100 games – 27 more wins than in 1968. They chased the Cubs most of the season. A newspaper in Chicago ran a daily cartoon of Cubs manager Leo Durocher showing the team’s current magic number. When the Mets moved into first place in September, the cartoon disappeared. The Mets finished with a 38-11 surge and won the Eastern Division by eight games. Many players had career years. Seaver won the Cy Young Award with a record of 25-7.

1969 NLCS: Although the Mets won the most games in the NL, they still did not own the pennant. Each league had expanded to 12 teams in 1969 and divided into two six-team divisions for an extra round of postseason play. In the NL, the Mets won the East and faced the Atlanta Braves of the West in a 5-game Series. The Mets swept the Braves in three games to take the NL pennant. Next stop, the World Series.

1969 World Series: The American League pennant was won by the Orioles. They won 109 games that year and were heavily favored over the Mets. Led by Brooks Robinson and Frank Robinson, the Orioles had won the World Series in 1966, and they would also go on to play in the World Series in 1970 and 1971. A dynasty team.

In the clubhouse after the ALCS, Frank Robinson said “We’re going to whip the Amazin’ Mets. The World Series might go five or it just may go four…the Birds haven’s decided yet. We’re here to prove there’s no Santa Claus.” Or did he mean to say “no miracle”?

Frank was right about a short series, but he had the team wrong. The Mets lost the first game, but won the next four to win the World Series. The O’s got only nine runs in five games and hit .146. Casey Stengel attended and said “You can’t be lucky every day, but you can if you get good pitching.” Mid-season acquisition Donn Clendenon slugged three homers and hit .357 to win the Series MVP Award.

Miracle or not, the Mets were the 1969 World Champions and New York celebrated.

1994 World Series (Not): The first World Series was played in 1903, and the Boston Americans (later Red Sox) beat the Pittsburgh Pirates. In 1904, Boston again won the AL, and the New York Giants won the NL. Giants manager John McGraw declined to meet the winner of the “junior” (or “minor”) league. McGraw declared that the Giants were champions of the “only real major league.” The leagues agreed that would not happen again and then 90 years went by…to 1994.

There was a nice logo for 1994, but no World Series. During the season, the owners and the union were negotiating a replacement for the collective bargaining agreement (CBA) that had expired. The negotiations failed, and the players went out on strike August 12. When the impasse continued into September, the postseason was called off.

The dispute carried over to 1995, and the owners prepared to start the season with replacement players. The union went to court and won a ruling from Judge (now Justice) Sonia Sotomayor that the owners had bargained in bad faith. The owners were forced to open spring training and temporarily operate under the expired CBA. Baseball was back.

The American League player representative in the labor negotiations was David Cone of the Royals. When President Obama appointed Sonia Sotomayor to the Supreme Court in 2009, Cone was among those testifying on her behalf at the Senate confirmation hearings. Speaking of David Cone…

The Royals in 1994: The Royals were playing well when the 1994 season was cut short. They had a record of 64-51 and were four games behind the first place White Sox in the Central Division. Two of their players received major awards: David Cone won the AL Cy Young and Bob Hamline was the AL Rookie of the Year.

Cone was originally drafted by the Royals in 1981, but was traded to the Mets in 1987. He moved to Toronto in 1992 and became a free agent at the end of the season. He was then signed by…the Royals. He played in KC in 1993 and 1994 before moving on to other teams to complete a 17-year career. In recent years, he has been a color commentator for Yankees TV games. This season, the Yankees had a David Cone bobblehead night to celebrate the 20th anniversary of his perfect game against the Expos at Yankee Stadium on July 18, 1999.

Cone’s career and his take on the philosophy and science of pitching are the subjects of a book published earlier this year with co-author Jack Curry (Full Count: The Education of a Pitcher). My old friend Jay DeSimone gave me a copy signed by Cone. It’s a good read.

Lonnie’s Jukebox – 1969 Series: Woodstock was an example of good music in 1969, but just as impressive is the list of Billboard’s top 100 songs of the year. Check out the list here. Some real classics. Many great artists (except for the top song of the year – “Sugar, Sugar” by the Archies, a fictional band). Skipping past that one leads to the Stones, CCR, Tommy James, Sly and the Family Stone, Temptations, Three Dog Night, Elvis, Doors, Dylan, etc. Three songs from the Broadway musical Hair. The Boston Red Sox 8th inning anthem, “Sweet Caroline.” Johnny Cash’s biggest single, “A Boy Named Sue.” A Beatles record with a hit on both sides, “Something” and “Come Together.”

Too many to choose from. So I’m taking an objective approach and linking the three that spent the most time at #1:

7 weeks – Marvin Gaye – “I Heard it Through the Grapevine”

6 weeks – Zager and Evans (one-hit wonder) – “In the Year 2525”

6 weeks – Fifth Dimension – “Aquarius/Let the Sunshine In”

Lonnie’s Jukebox – 2019 Series: In January of this year, a new hit entered the Billboard charts. It was Pinkfong’s “Baby Shark.” It went viral. A real earworm. And I missed the whole thing.

But the Washington Nationals have educated me. Have you seen their fans and players doing that shark motion thing? Click here for a video (1:37).

Early in the season, Nationals outfielder Gerardo Parra was in a slump (0-22), and the team still had a losing record (33-38). Parra decided on a change. He chose a new walk-up song, an earworm ditty that his 2-year-old daughter kept playing at home. Parra started hitting, the catchy song was embraced, and “Baby Shark” evolved from a walk-up song to an anthem for the team. Sales of shark toys and costumes shot up in the Washington area – they can be seen all over Nationals Park.

Click here for an animated version of the song (2:16; note that this version has been watched some 3.7 BILLION times). Caution: You may catch yourself hearing “doo doo doo doo doo doo” the rest of the day.

Go Baby Sharks! Go Nationals!

///

This electronic mail message contains CONFIDENTIAL information which is (a) ATTORNEY – CLIENT PRIVILEGED COMMUNICATION, WORK PRODUCT, PROPRIETARY IN NATURE, OR OTHERWISE PROTECTED BY LAW FROM DISCLOSURE, and (b) intended only for the use of the Addressee(s) named herein. If you are not an Addressee, or the person responsible for delivering this to an Addressee, you are hereby notified that reading, copying, or distributing this message is prohibited. If you have received this electronic mail message in error, please reply to the sender and take the steps necessary to delete the message completely from your computer system.