The sports pages and news pages are filled with “collusion” talk. But the Russians are not coming to Hot Stove. Just baseball.

Over the last several years, baseball owners have been in competitive pursuit of free agents. Big-dollar/long-term contracts were the norm. Not so much in 2018. What happened?

There are two primary schools of thought on this. One is that the owners have found that the big contracts have not resulted in the expected return in performance. The other is that the owners are colluding in an effort to reduce salaries and increase team profits – just as the owners did in the 1980’s, costing them $280 million in damages paid out to the players.

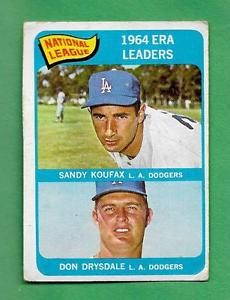

That big damage payment by the owners had its genesis in a two-man holdout in spring training of 1966. I knew about the Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale holdout, but did not know that it had a key connection to the baseball collusion battles of the 1980’s. Over lunch one day with long-time friend and fellow Kansas City lawyer Steve Fehr, I got the scoop.

Some background on Steve: his labor practice has included working as a sports agent (David Cone, Frank White, Dan Quisenberry) and as special counsel to the Major League Baseball Players Association (MLBPA). We met back in the 1970’s while working on political campaigns where we also each met a future wife (each keeping her last name). Steve’s wife Cynthia Wendt is one of the biggest sports fans I know, especially of the Royals and KU (which she did not attend, but as Steve says, “One of her standard jokes is that when she married me she converted to Judaism and KU basketball, but not necessarily in that order.”).

Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale: In the 1965 season, three players for the Los Angeles Dodgers finished in the top five of the MVP voting: Sandy Koufax (2nd), Maury Wills (3rd) and Don Drysdale (5th). The Dodgers won the pennant and beat the Twins in the World Series. The players were looking for big raises, but this was long before a strong union and any right to move to another club. The leverage for players was limited to not playing. Koufax, Wills and Drysdale threatened to do just that and became holdouts when spring training opened in 1966.

Dodgers’ owner Walter O’Malley told shortstop Maury Wills that the two pitchers “might be able to get away with this, but you can’t.” Wills quickly caved, “He put a contract in front of me and I signed it. I didn’t even look at it.”

Koufax and Drysdale remained out. They had won a combined 49 games in 1965 and felt that a joint holdout might net them a big raise. They waited it out while working on a movie at Paramount Studios where they had potential roles in the David Janssen film Warning Shot.

The pitchers knew that Willie Mays, the MVP, had just signed for two years at $125,000 per year. The team offers had been $100,000 for Koufax (a $15,000 raise for his 26 wins) and $85,000 for Drysdale (a $5,000 raise for his 23 wins AND 7 home runs). The Dodgers’ general manager Buzzie Bavasi worked the media and the fans to discredit the players. This was a big discouragement to them after they had led the Dodgers to the title.

After a 32-day holdout, the players signed new contracts. Koufax – $125,000, Drysdale – $110,000. Better numbers, but neither side was pleased. As Bavasi wrote in a Sports Illustrated:

“To tell the truth, I wasn’t too successful in the famous Koufax-Drysdale double holdout in 1966. I mean, when the smoke had cleared they stood together on the battlefield with $235,000 between them, and I stood there with a blood-stained cashbox. Well, they had a gimmick and it worked; I’m not denying it. They said that one wouldn’t sign unless the other signed. Since one of the two was the greatest pitcher I’ve ever seen (and possibly the greatest anybody has ever seen), the gimmick worked. But be sure to stick around for the fun the next time somebody tries that gimmick. I don’t care if the whole infield comes in as a package; the next year the whole infield will be wondering what it is doing playing for the Nankai Hawks.”

So Bavasi gave his “warning shot” to any players who might collude in the future. Little did he realize that the owners were the ones getting a warning shot.

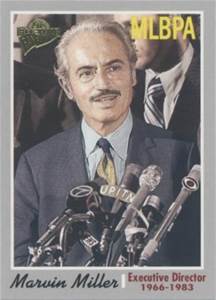

Marvin Miller: In a separate but related story in spring training of 1966, Marvin Miller was going from team to team to speak to the players. Miller was an economist and negotiator for the Steelworkers Union, and he was seeking to be named the next Executive Director of the MLBPA. Miller was told by Minnesota player rep Bob Allison (Raytown native) that he might want to shave off his mustache before meeting with players who in those days were all clean shaven. Miller declined, and he and his mustache won the vote 489-136.

Koufax and Drysdale did not vote because they were holding out and not at spring training. Miller spoke with Koufax at the all-star game that year and congratulated him on standing up to Walter O’Malley and Buzzi Bavasi. Maury Wills, who had cut short his holdout, was also in the all-star game and talked with Miller after the game. Wills lamented the indignities still suffered by minorities, especially in Jim Crow Florida in spring training. Wills had enthusiastically supported Miller and told him “The black and Latin ballplayers are especially eager to support the union. Discrimination is not dead.”

[Steelworker Trivia: Miller worked for the Steelworkers Union from 1950 to 1966. My dad was a machine operator at Sheffield (later Armco) Steel for some 35 years and was a proud member of the Steelworkers Union. When Miller was doing his team meetings, the Phillies’ Robin Roberts suggested that Miller hire former VP Richard Nixon as general counsel for the association. Miller said he would not take the job if he had to hire Nixon. Miller got his way and instead hired one of the Steelworker Union’s in-house lawyers, Dick Moss. It would prove to be one of his smartest moves.]

Miller’s early successes were getting bumps in minimum salaries and better pension benefits. He also helped the players earn more money on licensing the use of their names – such as on baseball cards.

With the union firmly in place, labor relations were now regulated by a collective bargaining agreement (CBA) between the players and owners. The CBA was for a fixed period, subject to renegotiation when it expired. One of the key provisions Miller bargained for was the use of a 3-party arbitration panel to settle grievances under the CBA. The panel would have one rep for the players, one for the owners, and a neutral member jointly picked by the other two.

He also had a big target in mind – the reserve clause.

The Reserve Clause: In the early days of the major leagues (really early, the 1800’s), teams began using “reserve” clauses to keep players from jumping to other teams or leagues for higher salaries. When a player signed a contract for an upcoming season, he also agreed to be “reserved” to play for the same team the following season. The player had two choices for the following season: (i) play for the same team at the salary designated by the team, or (ii) quit baseball. The team also had the power to trade the player without player consent.

All of the teams agreed that they would not attempt to sign any player so reserved. The result was full control of both player salaries and movement of players among teams – some called it slavery with better (but owner controlled) wages. It was also called anti-competitive and a monopoly, possibly in violation of the Sherman and Clayton Antitrust Acts.

Oliver Wendell Holmes to Curt Flood: In 1913, the Federal League came into existence and enticed players to jump from other leagues. In 1914, the Federal League decreed that it was a major league, but would operate without a reserve clause – a player friendly move. The American and National Leagues fought back hard, and the Federal League filed an antitrust suit after the 1914 season. The case languished in court while the 1915 season played out (the judge was Mountain Kenesaw Landis who would become the first baseball commissioner in 1920). The league folded after 1915 with most Federal League owners being bought out or merging their teams within the old leagues. But the Baltimore Terrapins’ owners were not satisfied and filed a new antitrust lawsuit.

[Federal League Trivia: One team did not need to get bought out. The Kansas City Packers were bankrupt at the end of the 1915 season. More on them in a Hot Stove post to be named later.]

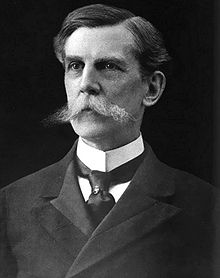

Justice Holmes

The litigation filed by the Baltimore team slowly moved through the court system until a decision was finally handed down by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1922. Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, speaking for a unanimous court, held that baseball was not involved in interstate commerce (what?) and therefore not subject to Federal antitrust laws. “The business is giving exhibitions of baseball, which are purely state affairs…the exhibition, although made for money, would not be called trade or commerce…personal effort, not related to production, is not a subject of commerce.”

And so the monopoly (and the reserve clause) remained safe. The decision went uncontested until 1953 when a Yankee minor leaguer, George Toolson, wanted to try to reach the majors with another team, but could not do so because of the reserve clause. The Supreme Court, in a 7-2 decision, upheld the Federal League precedent because the owners had been developing their business over the last thirty years on the understanding that they were not subject to antitrust legislation. Oliver Wendell Holmes may have made some bad law, but the court said it was now up to Congress to fix.

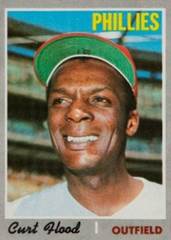

The next man up to bat at the Supreme Court was Curt Flood who was traded by the Cardinals to the Phillies after the 1969 season. Flood refused to report and filed suit to challenge the reserve clause (arbitration was not available because it was not yet in the CBA). He felt like he was being treated as a “piece of property to be bought or sold.” Flood succeeded in raising the visibility of the issue, but he lost his case on a 5-3 vote. He did change the mind of one Justice who had voted with the majority in the Toolson case. Judge William O. Douglas now dissented (as did Justices Bill Brennan and Thurgood Marshall), saying:

“I have lived to regret [Toolson]; and I would now correct what I believe to be its fundamental error…Baseball is today big business that is packaged with beer, with broadcasting, and with other industries. The beneficiaries of the Federal Baseball Club decision are not the Babe Ruths, Ty Cobbs, and Lou Gehrigs. The owners, whose records many say reveal a proclivity for predatory practices, do not come to us with equities. The equities are with the victims of the reserve clause. I use the work “victims” in the Sherman Act sense, since a contract that forbids anyone to practice his calling is commonly called an unreasonable restraint of trade.”

Even the majority opinion of Justice Harry Blackmun conceded the lack of logic in saying that baseball was the only professional sport entitled to a judicial exemption to the antitrust laws.

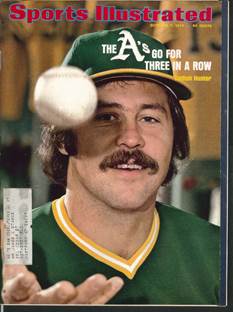

Catfish Hunter: After helping lead the Oakland A’s to World Series titles in 1972 and 1973, James Augustus “Catfish” Hunter signed a new 2-year contract with owner Charlie Finley. Part of the agreement was that Finley would make payments for an annuity. The A’s won another World Series in 1974, but then Hunter discovered that Finley had not paid for the annuity. Hunter claimed that the remedy was termination of the contract. The dispute went to arbitration under the CBA, and neutral arbitrator Peter Seitz (remember that name) ruled that Hunter was a free agent for the 1975 season.

Hunter was courted by almost every team and signed with the Yankees to become the highest paid player – by far – with a previously unheard of guaranteed multi-year contract. The arbitration decision had nothing to do with the reserve clause, but it loudly announced to the players and owners the value of free agency.

[Mustache Trivia: Note that the last three photos show men with mustaches.]

Marvin Miller’s Plan: Marvin Miller had a theory. What if a player signed a contract for one season (say 1972) and then played the next season (1973) as required by the reserve clause – but did not sign a new contract in 1973. Just played out 1973 as required by his 1972 contract. The 1972 contract said nothing about 1974. Had the reserve right run out? Not automatically renewed from year-to-year? Was the player a free agent in 1974?

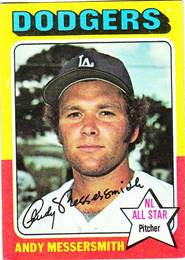

Miller needed a test case. This meant some player would need to play out a reserve year without signing a new contract. Several players started the 1975 season without signing contracts, but the teams upped some salaries to sign most of them. But two did not sign new contracts: Andy Messersmith (Dodgers) and Dave McNally (Expos). McNally was planning to retire, but the association wanted to establish that he was nevertheless a free agent if he came out of retirement. The Expos tried to buy him off, but he wanted to stay in for the benefit of other players. He was also the backup if Messersmith made a deal with the Dodgers. Both pitchers got the same result, but I’ll uses Andy’s facts to tell the story.

Andy Messersmith Case: The Dodgers best pitcher in the mid-60’s was Sandy Koufax. In the mid-70’s, it was Andy Messersmith. In both cases, Dodger owner Walter O’Malley did not like their demands for higher pay. Koufax held out for more money, but never questioned the reserve clause. Messersmith took the next step.

In 1974, Andy had a record of 20-6 with an ERA of 2.59, finishing second in Cy Young voting. He thought he deserved a substantial raise and was not happy with the $115,000 offer from the Dodgers. At the suggestion of Marvin Miller, Andy did not sign a contract for 1975. He was still bound to play for the Dodgers in 1975 because of the reserve clause in his 1974 contract. He had another good season, finishing at 19-14 with an ERA of 2.29. With the knowledge that Andy might test the reserve clause, the Dodgers were willing to pay a better salary, but would not bend on giving Andy a no-trade clause.

Andy claimed he was now a free agent and could sign with any club for the 1976 season. The Dodgers disagreed. The grievance went to the 3-person arbitration panel under the CBA. The members representing the owners and players voted as expected. The impartial member, Peter Seitz, sided with the position of the players, and what became known as the “Seitz Decision” made Andy Messersmith and David McNally free agents on December 23, 1975.

In litigation filed in the Western District Court of Missouri in Kansas City (the lead plaintiff was the Kansas City Royals), the owners argued that the reserve clause was not subject to arbitration and therefore the Seitz Decision should be set aside. The case was heard by Judge John Oliver who ruled for the players, and his decision was affirmed by the 8th Circuit on March 9, 1976.

[Lawyer Trivia: The players were represented in the Federal Court litigation by their general counsel Dick Moss who brought in KC attorneys Bill Jolley and Don Fehr to help with the case. In 1977, Fehr succeeded Moss as general counsel to the association. Moss became an agent for individual players, and his young associate in that business was Steve Fehr, Don’s younger brother. The teams were represented by Harry Thomson of Shughart, Thomson and Kilroy, a firm that merged in 2009 with the firm of Polsinelli, Shalton, Flanigan and Suelthaus.]

Don Fehr, Marvin Miller, Dick Moss

It was a whole new ball game.

The 1976 Collective Bargaining Agreement (CBA): As Steve Fehr would lay out for me in our lunch, this is when the roles played by Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale in this saga came into play.

In the wake of the Messersmith case, the owners and players now needed to deal with free agency rules in the CBA. Neither the players nor the owners wanted full free agency from year to year. The owners wanted control as long as possible, and the players didn’t want to have 600 players flooding the market every year – the key was spreading free agency out so that supply did not outstrip demand. The argument would be over the number of years before free agency and the use of arbitration for a period prior to free agency. There was also a wild card: the Koufax/Drysdale issue.

The owners were worried that players might use their free agency to act in unison as Drysdale and Koufax had done ten years earlier. So the owners asked for a prohibition against such player collusion. Marvin Miller said sure, but what is good for the goose is good for the gander. This led to the “individual nature of rights” clause which says that the players AND clubs must act solely in their own individual self-interest:

“The utilization or non-utilization of rights under [free agency] is an individual matter to be determined solely by each Player and each Club for his or its own benefit. Players shall not act in concert with other Players and Clubs shall not act in concert with other Clubs.”

The owners got what they were after: star players would not be able to hold out as a group. But the added clause for the “gander” owners would someday be their undoing.

1981 Strike: Before the ink was dry on the 1976 CBA, the owners started looking for ways to weaken free agency. As the owners feared, salaries escalated and stars changed teams. Reggie Jackson moved from Baltimore to the Yankees, Pete Rose from Cincinnati to the Phillies and Nolan Ryan from the Angels to Houston. The bitterness reached a boiling point in 1981 with the owners insisting on changes that left the union with no effective remedy other than a strike. They did so in June and July with a total of 713 games cancelled before a settlement was reached. The players stayed unified and the owners (who had divergent goals) made little progress.

Changing of the Guard: Marvin Miller retired at the end of 1982, leaving behind a series of victories – achieving bona fide collective bargaining, a grievance and impartial arbitration procedure, salary arbitration, free agency and safeguards against owner collusion. As noted in the press, the MLBPA was “unbeaten, untied, and unscored upon.” The players had become loyal union members and they were handsomely rewarded. As Peter Seitz would later write, Miller was the “Moses who led Baseball’s Children of Israel out of the land of bondage.” Miller’s replacement was Ken Moffett, but he was ousted by the players in less than a year. In December of 1983, Moffett was replaced by Don Fehr, the general counsel who had worked closely with Miller for many years.

Marvin Miller and Bowie Kuhn

Miller’s counterpart Bowie Kuhn had been commissioner since 1969. Kuhn was an imposing figure at six-feet-five, but Miller found that “one didn’t have to deal with Kuhn for very long in order to be unimpressed by his height.” Kuhn’s employers, the team owners, were also not impressed with Kuhn and forced him out in 1984. So a new sheriff came to town – Peter Ueberroth. As colorfully described by George Vecsey in the New York Times: “Ueberroth knew he would be entering murky waters with the 26 assorted sharks, whales, sting rays, sea turtles and barnacled mossbunkers in baseball’s sea of ownership.”

Ueberroth famously lectured the owners in St. Louis during the 1985 World Series (Cardinals/Royals). In a meeting at the headquarters of Anheuser Busch (Gussie Busch being one of the hardline owners), he told them…

“If I sat each one of you down in front of a red button and a black button and I said, ‘Push the red button and you’d win the World Series but lost $10 million. Push the black button and you would have a $4 million profit and you’d finish in the middle.’ You are so damned dumb. Most of you would push the red button. Look in the mirror and go out and spend big if you want, don’t go out there whining that someone made you do it…You all agree we have a problem. Go solve it.”

As Marvin Miller later described, it was “tantamount to fixing, not just games, but entire pennant races, including all post-season series.” The new Black Sox.

[Game 3 Trivia: Although I did not know about it at the time, I was in St. Louis when Ueberroth lectured the owners. I was there with my friends Rich and Mary Ellison to see our Royals start their comeback against the Cardinals. Steve Fehr remembers the date as being on the day of Game 3 of the Series – that was also the day his wife Cynthia told him she was pregnant with their first child. And the day his client Frank White batted cleanup and hit a crucial 2-run homer and a run-scoring double to sew up the Game 3 victory.]

Collusion Cases: The owners took to heart what Ueberroth had told them. They understood that his message could be reduced to one word: collusion. That story will be in Part Two to be posted as Hot Stove #73.

Curt Flood Trivia: Flood missed the entire 1970 season. In 1971, his owner (the Phillies) traded him to the Washington Senators. He appeared in only 13 games before he became discouraged and retired. So Flood never wore a Phillies uniform, but the Topps baseball card company did not know that would be the case when they issued their 1970 cards. Topps took an old Cardinals photo with the hat logo hidden and made Curt a Phillie.

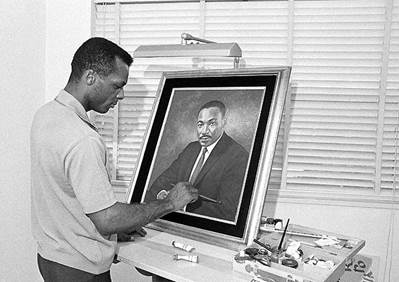

Curt Flood was also an artist of some talent. Below, putting the finishing touches on his portrait of Martin Luther King Jr.

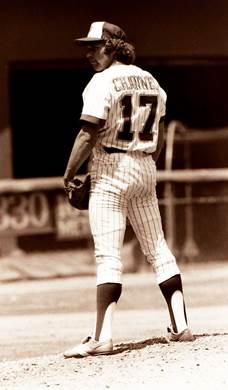

Andy Messersmith Trivia: Free agent Andy Messersmith spurned his old team, the Dodgers, and signed with the Atlanta Braves. In 1976, the Braves started putting player nicknames on their uniforms, and the one chosen for Andy drew the ire of the league. Andy was #17, the same as the channel number for superstation TBS owned by Braves owner Ted Turner. Turner thought it would be fun (and good advertising for his station) to give Andy the nickname “Channel.” The league fined Turner and Andy’s nickname was changed to “Bluto.”

After two years with the Braves, Andy was traded to the Yankees for the 1978 season. He was then released after an injury-plagued season – which made him a free agent again. Ironically, he was signed for 1979 by the Dodgers. This time they gave him a no-trade clause, the very clause they refused to give that led to the reserve clause arbitration. Andy only played a partial season before retiring after being released.

Lonnie’s Jukebox – Hill Street Blues: Steven Bochco died earlier this month at age 72. He was the creator, producer and writer of some of my favorite TV shows: Hill Street Blues (1981-1987), L.A. Law (1986-1994) and NYPD Blue (1993-2005). One of Bochco’s early pieces of work was a good signal of where he was headed. In 1971, the premier episode of Columbo was written by Bochco and directed by Steven Spielberg. Bochco mentored many others who would also go on to produce quality television, including David Milch (Deadwood) and David Kelley (Ally McBeal and Boston Legal).

After actor Dennis Franz became a scene stealer as Lt. Norman Buntz in Hill Street Blues, Bochco later cast him as Detective Andy Sipowicz in NYPD Blue. Andy became one of TV’s most popular antiheroes, leading the way for the genre that spawned Tony Soprano, Dexter, House and Breaking Bad’s Walter White.

[Dennis Franz Trivia: Rita and I have some personal history with Dennis Franz. He started his acting career in Chicago and one of his fellow young actors was my cousin, Tom Myers. They both moved to L.A. and remained friends. Tom married Marcy Vosburgh who was a TV writer whose credits included The Jeffersons, Married with Children, Unhappily Ever After and Caroline in the City (Caroline being their neighbor Lea Thomson).

Tom and Marcy lived in a modern home that they had built in the hills above Hollywood. The unique architecture of their house (from Tom’s ideas) led to its use as a location for TV and movies. In one of the early years of Curb Your Enthusiasm, Rita and I were watching the show and eagle-eye Rita ID’d the house’s interiors – as it turned out, it was used on the TV show for several seasons as the home of Larry David’s manager Jeff Greene).

The house had a private apartment above the garage, and Rita and I had the pleasure of staying there several times. On one of those visits, Tom and Marcy hosted a dinner party that included Dennis Franz and his wife Joanie. Also at the table were actors Nikki Cox and Kevin Connolly (Entourage) who were then cast members on Unhappily Ever After. Apologies for the name dropping, but it was a delightful evening.]

As much as I like the opening music of Mash, Mission Impossible, Cheers and Curb Your Enthusiasm, it’s hard to top the opening bars of Mike Post’s theme from Hill Street Blues. Click here to listen and also see shots of the superb ensemble cast (1:21).

And as you await Hot Stove #73, remember the weekly caution in the squad room from Sgt. Phil Esterhaus: “Let’s be careful out there” (Click here).