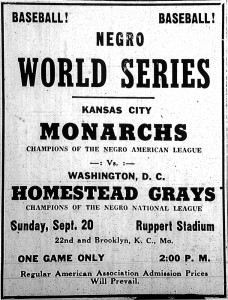

Hot Stove #62 covered the 1942 MLB World Series between the Cardinals and Yankees. Now for the counterpart from the Negro Leagues.

1942 – Kansas City Monarchs v. Washington Homestead Grays: Under the cloud of war, the Negro Leagues entered the 1942 season.

The 1942 Monarchs may have had the best team in the storied history of the franchise. The pitching staff was so good that one pundit quipped that the infielders “have come close to getting arrested for loitering.” Buck O’Neil, the bard of Negro League baseball and first baseman of the Monarchs, said in his autobiography I Was Right on Time,

“…1942 was my favorite year…the 1942 Monarchs…were the best team I ever played with. Someone asked Newt Joseph who he would take with him if he could play in the major leagues, and Newt replied, ‘The whole Monarchs team.’ That’s the way I felt about the ’42 Monarchs. I do believe we could have given the New York Yankees a run for their money that year.”

The Homestead Grays were also baseball royalty. They were founded in Homestead, Pennsylvania, in 1912, and by the 1920’s were playing their home games in Pittsburgh. From 1940 to 1942, they played about half their “home” games in Washington, D.C. Hence, they were often known as the Washington Homestead Grays. Two of their stars, Josh Gibson and Buck Leonard, were the second and third Negro League players inducted into the Hall of Fame (1972). The first was Satchel Paige in 1971.

In the six seasons from 1937 to 1942, the Monarchs won the Negro American League pennant five times. Ditto for the Grays in the Negro National League. With the two premier Negro League teams winning their respective pennants in 1942, it was an opportune time to schedule a World Series, the first since 1927. Again quoting Buck O’Neil, “For a fan of black baseball, a Monarchs-Grays World Series was a dream come true, although we were definitely the underdogs.”

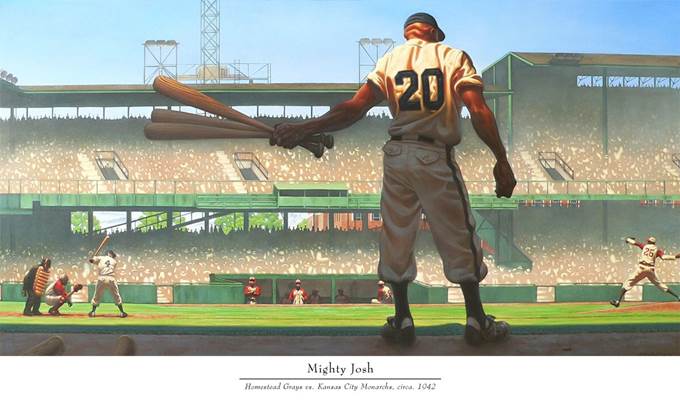

In addition to the team rivalry, the fans were excited to see the faceoff between the best pitcher and hitter in Negro Leagues history – Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson. They would not be disappointed. This “Mighty Josh” artwork by Kadir Nelson shows Gibson on deck at Griffith Stadium in DC, circa 1942, and a pitcher who looks like Satchel Paige on the mound.

Game 1 of the 1942 Series was played in DC’s Griffith Stadium, one of the two home fields of the Grays. Satch started the game and pitched five innings of 2-hit ball. Jack Matchett relieved Satch and allowed no hits the rest of the way. The Monarchs won 8-0.

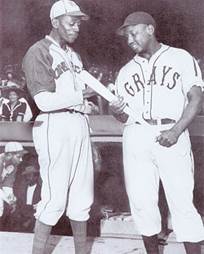

For Game 2, the Series moved to the other home of the Grays, Forbes Field in Pittsburgh. This game has long been part of Negro Leagues lore because of the various versions of the facts that go with this headline: SATCH STRIKES OUT JOSH GIBSON WITH BASES LOADED.

Hilton Smith started for the Monarchs and pitched five hitless innings for a 2-0 Monarchs lead. Satch then entered the game. It was still 2-0 in the bottom of the 7th when the fans saw “the most famous confrontation in the history of black baseball, one that boiled down a hundred years of history into one at-bat” – as recalled by Buck O’Neil who then became part of the show and told this story.

With a man on third and two out, Satch called Buck to the mound to let him know that he was going to intentionally walk the next two batters so he could face his archrival Josh Gibson for the third out. Buck frantically called manager Frank Duncan to the mound to tell him “what this fool wants to do.” Duncan’s response: “Buck, you see all these people out here? They came to see Satchel pitch to Josh.”

All the while taunting Gibson, Satch walked the two batters to load the bases and bring Josh to the plate. But the great showman Paige was not done setting the stage. He claimed that his well-known stomach problems were acting up and called out the trainer to bring him his bicarbonate of soda. He drank it down and let out a big belch. “He was playing the crowd like a fiddle.” Satch then threw three fastball strikes that were so good that Josh never took a swing.

Satchel and Josh

Satch, Buck and others have told various versions of that day. There is also a version from contemporary newspaper reports: The bases had been loaded with three singles and there were two outs. Gibson indeed struck out, but not by taking three pitches. As one paper reported, “Josh fouled off the first two tosses weakly, then fanned on the third.” The box score shows that Paige did not walk anyone in the game.

I enjoy Buck’s version, apocryphal as it might be. Buck said that this was the story that everyone always wanted him to tell at banquets. You can still hear him tell it via YouTube (3:32; click here).

Now back to the game. The Monarchs scored three in the 8th to make it 5-0, but Paige gave up four runs in the bottom of the 8th to reduce the lead to 5-4. The Monarchs scored three more in the 9th and won the game 8-4.

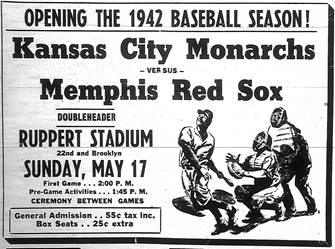

Game 3 could not be in Kansas City because the minor league Blues were also in postseason play and had preference on Ruppert Stadium. So the game was played at Yankee Stadium, a popular stop for Negro League teams because of the good crowds. Satch pitched only the first two innings, and the Grays took a 2-0 lead. The Monarchs took the lead with back-to-back homers by Ted Strong and Willard Brown, leading the way to a 9-3 win. Below, Willard “Home Run” Brown crossing the plate after his homer, greeted by Joe Greene while catcher Josh Gibson looks on.

The Monarchs led the Series three games to none. And they were now “Goin’ to Kansas City.” [More on that in Lonnie’s Jukebox below.]

The Monarchs hoped to complete a sweep by winning Game 4 in front of their home fans at Ruppert Stadium. But it was not to be as the Grays won 4-1. Or not. Monarchs owner J. L. Wilkinson quietly filed a protest because the Grays had brought in several ringers to replace injured players. Wilkinson did not try to stop the game from being played – he still wanted the gate receipts from the big crowd. One of the ringers was pitcher Leon Day (on loan from the Newark Eagles) who outpitched Satchel Paige that day for the victory. However, the league officials upheld Wilkinson’s protest and this first Game 4 was thrown out.

The second Game 4 was scheduled for Chicago, but bad weather forced a move to Shibe Park in Philadelphia, the fifth different city for the five games. Again, Satchel Paige was the story, and I’ll recount it the way Satch told it in his autobiography Maybe I’ll Pitch Forever.

On the night before the Philadelphia game, Satch was in Pittsburgh. “As much as I was thinking about the series, there was a mighty nice gal over there that I just had to see.” The next morning, he hopped in his car to drive the 300 miles to Philly. “I really stepped on the gas and was clipping right along when I heard this siren while I was busting through Lancaster.” He pleaded with the officer, “But I got to pitch a ball game over in Philadelphia – the World Series.” The response from the officer: “All you got to do is see the justice of the peace.”

They went to town and stopped in front of the barber shop. Satch said “I don’t have any time for haircuts.” Officer: “Just mind your tongue. The justice of the peace is the barber.” Satch had to sit while the barber “finished snipping,” and he then pled guilty and paid a three dollar fine. He hopped back in his car and resumed at an even higher speed, but luckily did not get stopped again. He arrived at the park in the fourth inning.

The Monarchs were behind 5-4 when Satch entered the game with two outs and two on in the 4th. He wasn’t warmed up, so he “tried picking off that runner on first about ten times until I got loosed up.” He struck out the batter to end the 4th inning, and over the next five innings, the Grays never got a hit off of Satch. The Monarchs meanwhile scored five more runs to win the game 9-5 and sweep the Series.

Satchel’s take on the game: “Sometimes it seems to me like that was the best day I ever had pitching. Maybe it was, but when a fellow has pitched two thousand or more games there’s a lot of best days.” Amen to that.

The Monarchs had dominated the Series. They scored a total of 34 runs to the Grays 12. The Monarchs team hit .345 while the Grays struggled at .206. Josh Gibson hit .077. Counting the game that was thrown out, Satchel Paige appeared in all five games.

Hall of Famers: Seven players from this 1942 Series are enshrined at Cooperstown. The Monarchs: Satchel Paige, Hilton Smith, Willard “Home Run” Brown. The Grays: Josh Gibson, Buck Leonard, Ray Brown, Jud Wilson.

If the first Game 4 had counted, there would be two more in the Hall of Fame from the 1942 Series. Leon Day, the winning pitcher in that game, is in the HOF. Also, since the game was in KC, local umpire Bullet Joe Rogan was part of the umpiring team. Rogan was a long time pitching star for the Monarchs and is in the HOF.

1942 – Monarchs v. One of the Cardinals: With baseball apartheid still firmly in place, the Cardinals and Monarchs would not be playing each other in 1942. But the Monarchs did face an all-time Cardinal great, Dizzy Dean. By 1942, Dean had finished his major league career, but he kept active with a barnstorming all-star team. Any pairing of Dean and Satchel was bound to be a draw, so to raise funds for the war effort, the Monarchs agreed to an exhibition against Dean’s team. The game was played before 30,000 fans at Wrigley Field, the first time a Negro League team was allowed to play at Wrigley.

Satchel was also loaned to the Homestead Grays for a similar fund raiser against Dean’s all-stars in Washington, D.C. Major League Commissioner Kenesaw Landis then put a stop to such games by telling MLB owners to not rent their parks for interracial fundraisers.

Satch and Dizzy at Wrigley Field – 1942

Baseball and War: Just like the Major Leagues, the Negro Leagues started losing players through enlistment and the draft. Seven players from the 1942 Monarchs ended up in the war, including Willard “Home Run” Brown, Buck O’Neil and player-manager Frank Duncan. When Duncan returned to manage the Monarchs in 1945, he mentored a returning war veteran who was playing his first professional season – Jackie Robinson.

The war added to the pressure for the Major Leagues to integrate. If black players could fight for the country, why not play baseball? The armed forces were still mostly segregated, but baseball was one of the places that provided an opening. Negro Leaguers Leon Day and Willard “Home Run” Brown led an integrated military all-star team that won the “ETO World Series” (European Theater of Operations).

Commissioner Kenesaw Landis and the owners continued the fiction that there was no color line. Sportswriters from black newspapers pushed hard for change. They were aided by Lester Rodney of the Communist Daily Worker who in 1942 started the “Judge Landis, Can You Read” campaign. In Rodney’s open letter to Landis, he began with the war card: “The first casualty lists have been published. Negro soldiers and sailors are among those beloved heroes of the American people who have already died for the preservation of this country and everything this country stands for – yes, including the great game of baseball.”

Landis would not budge even though many MLB players and some owners thought it was time. Landis died in November of 1944 and his successor was named in April of 1945. It was U.S. Senator Happy Chandler from Kentucky. Soon after he was named, Chandler met with two black sportswriters who wanted to know where he stood on integration of baseball. His response: “I’m for the Four Freedoms, and if a black boy can make it in Okinawa and go to Guadalcanal, he can make it in baseball.”

A few months later, Branch Rickey signed Jackie Robinson for the Dodgers.

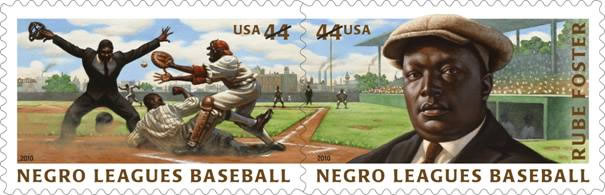

Art Gallery Report: Kadir Nelson, the artist who created the “Mighty Josh” piece shown above, also designed of the Negro Leagues Baseball stamps issued in 2010.

On the left side of the dual stamp is an umpire reminiscent of Bob Motley who recently had his statue unveiled on the Field of Legends at the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum. On the right is Rube Foster who was the force behind the founding of the National Negro League at the Paseo YMCA in Kansas City in 1920. Foster likewise is honored with a statue on the Field of Legends, as are four players from the World Series of 1942: Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson, Buck Leonard and Buck O’Neil.

At the new Rye Restaurant on the Plaza, on your left as you walk in, is this fabric Monarchs piece:

Lonnie’s Jukebox: The late 30’s and early 40’s were glory days for the Monarchs. They were heroes in the black community and this meant quite a bit of time in the “fifty night clubs between 12th and 18th Streets,” quoting Buck O’Neil who used a whole chapter in his autobiography to describe the nightlife. “The club owners loved the Monarchs to patronize their establishment because we attracted a crowd, so they often gave us free drinks. We all might have become drunks, but most of the bartenders had been instructed by Wilkie [Monarchs’ owner J. L. Wilkinson] to cut us off if they thought we couldn’t handle anymore.”

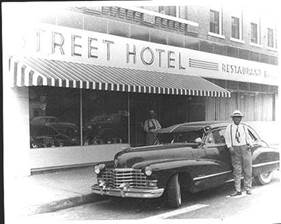

“At 18th and Vine, you couldn’t toss a baseball without hitting a musician, and you couldn’t whistle a tune without having a ballplayer join in. Baseball and jazz, two of the best inventions known to man, walked hand in hand along Vine Street. We had Satchel Paige and Satchmo Armstrong; Blues Stadium, where we played our ball, and the Blue Room at the Streets, where we had a ball.” Kansas City was still wide open when “anything went, including prostitution, gambling and reefer.”

Buck’s reference to “Streets” was the Street Hotel where many of the players stayed and often saw the jazz and blues stars in the Blue Room. They mingled with Count Basie, Charlie Parker, Cab Calloway, Duke Ellington, Jay McShann and many others.

Another quote, this one from the autobiography of Satchel Paige: “The folks in Kansas City treated me like a king and you never saw a king of the walk if you didn’t see old Satch around Eighteenth and Vine in those days, rubber-necking all the girls walking by.”

Buck also mentions Big Joe Turner, the bartender and blues shouter who worked at the Sunset Club near 12th and Vine. Turner became an R&B recording star, and one of his first records was an ode to Piney Brown, the revered manager of the Sunset Club. Some of the lyrics of “Piney Brown Blues” may sound familiar: “Well I’ve been to Kansas City/Girls and everything is really alright…Yes I dreamed last night /I was standing at 18th and Vine.”

In 1952, two 19-year old songwriters who had never been to Kansas City wrote a song about the city based on listening to the records of Big Joe Turner. Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller wrote of goin’ to Kansas City to see some crazy little women while standing on the corner at 12th Street and Vine. The song was first recorded by Little Willie Littlefield in 1952 and became nationally known in 1959 when Wilbert Harrison recorded his version that went to #1.

So when you hear “Kansas City” – and you will at Royals stadium at the end of every game by either the Beatles (wins) or Wilbert Harrison (losses) – please reminisce with thoughts of Big Joe Turner, Buck O’Neil and Satchel Paige strolling from 12th to 18th on Vine. Or you can listen now by clicking here.