Starting in 2002, I have posted an annual message for Martin Luther King Jr. Day. For the last several years, the message has been part of Hot Stove, and last year’s post was titled “Buck O’Neil on the Mountaintop.” It told the story of how Buck O’Neil, like Moses and King, had been to the mountaintop and seen – but not entered – the “Promised Land.” For Moses, the Promised Land was Israel. For King, equality, as eloquently presented in his last speech, “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop.” For Buck, the Hall of Fame. He was on the ballot in 2006, but did not receive the needed votes.

As most of you know, Buck’s story has a joyous update. Last month, he was posthumously elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame (Hot Stove #179).

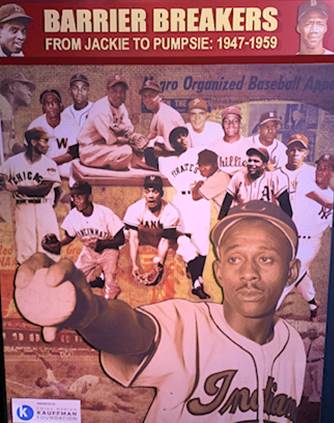

The subject for this 21st annual message – “Barrier Breakers” – involves another baseball “Promised Land” – the Major Leagues. [Note: When “Major League(s)” is used this post, I’m referring to the American League and National League, not the Negro Leagues (MLB corrected a longtime oversight in 2020 by recognizing that the Negro Leagues were indeed Major Leagues).]

Buck never reached that Promised Land. He loved his career in the Negro Leagues, saying to not shed any tears for him, “I was right on time” (the title of his 1996 autobiography). But he was proud of those who came after him and broke the color line. In his autobiography, Buck describes being in the Navy in the Philippines (below) when he heard that Jackie Robinson had been signed by the Dodgers.

“You should have heard the celebration. Halfway around the world from Brooklyn, we started hollering and shouting and firing our guns into the air. I don’t know that we made this much noise on VJ Day. This was progress. The Dodgers signing Jackie wasn’t just about baseball or about opportunities for the Negro-leaguers. This was progress for the whole country. It didn’t matter who was the first or which team had the courage; this was the first step toward integration, toward equality, since maybe Reconstruction.”

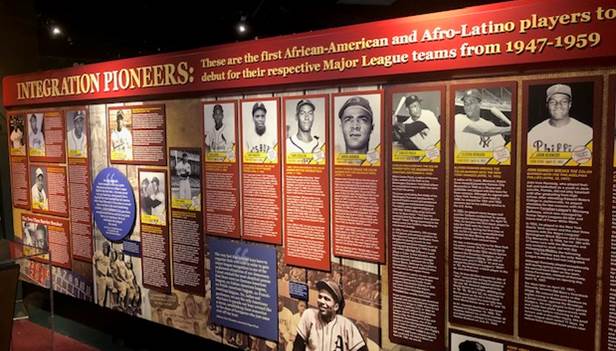

From 1947 to 1959, a brave contingent of “Barrier Breakers” broke the color line of the respective Major League teams. To put this long timeline on a personal scale, I was a five-year-old kindergartner when Jackie Robinson played his first game for the Dodgers in 1947. When the Boston Red Sox became the last team to integrate in the summer of 1959, I was 17 and getting ready to go to college.

These Barrier Breakers are the subject of an exhibit opened last year at the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum. I’ll briefly discuss each of them below, but to get the complete story, please visit the museum to view the exhibit.

I’m also going to sprinkle in some related history for context, starting with…

January 1, 1863 – Abraham Lincoln: On September 22, 1862, Abraham Lincoln issued the executive order known as Emancipation Proclamation. The effective date was January 1, 1863. Below, a print that hangs in my office. It depicts a group of slaves waiting by candlelight for the stroke of midnight when the Emancipation Proclamation would take effect and free them from bondage.

After the Civil War, actions were taken by Congress to implement the spirit of the Emancipation Proclamation. There were amendments to the Constitution and laws designed to secure equal rights for all citizens. Some of these were enforced by troops in the South. But this “Reconstruction” effort ended in 1877. It then did not take long for Jim Crow to weave itself into American culture.

Baseball was no exception. It had grown in popularity during the Civil War – a welcome diversion between battles. Baseball leagues began to spring up, most notably the National League in 1876. Other than some rare and short-lived exceptions, “organized baseball” was played only by white men. What would become the “Major Leagues” had no formal Jim Crow rule, but the owners instead relied on a misnamed “gentlemen’s agreement” to bar Blacks from the game. And it held for 70 years.

1946 – Branch Rickey and Harry Truman: Progress on civil rights got a big boost in 1946.

April 17, 1946 – Jackie Robinson took the field for the Montreal Royals. It was the beginning of “Baseball’s Great Experiment” engineered by Branch Rickey, general manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers. Robinson had played for the Kansas City Monarchs in 1945. Rickey signed Robinson for the 1946 season and chose Brooklyn’s affiliate in Montreal as the testing ground. It worked superbly. Robinson was the MVP of the International League and was cheered by the Montreal fans.

December 5, 1946 – President Harry Truman issued Executive Order 9808, establishing a President’s Committee on Civil Rights. Truman had been appalled at the violence against Black Americans, especially veterans who had served their country in WWII. Truman’s order was the first significant federal reply to racial violence since Reconstruction.

Baseball had acted first, but Truman was not far behind.

(1) April 15, 1947 – Brooklyn Dodgers (Jackie Robinson): Readers of Hot Stove know Jackie Robinson’s story. He was the first “Barrier Breaker” in Major League baseball, and on April 15 of each year, all MLB teams honor Robinson’s legacy.

What should also be remembered is that 15 more teams needed to be integrated, and in each case, a brave Barrier Breaker had to run the same gauntlet that Jackie Robinson had endured. As each joined a team, the same indignities were repeated. Many teammates were not welcoming. Team ownership and management did not always smooth the way. The Black players had to work in isolation. Look for hotels and restaurants that would serve them. Hear racist rants from fans and bench jockeys from the opposing teams. Much of the white press thought it was a bad idea, including the “Bible of Baseball,” the Sporting News. Spring training in the South was an ordeal.

But these men persevered. And got a little moral support from President Truman along the way.

June 29, 1947 – Harry Truman/NAACP: Truman became the first President to address the NAACP. Speaking from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, he repeated his call for progress on civil rights.

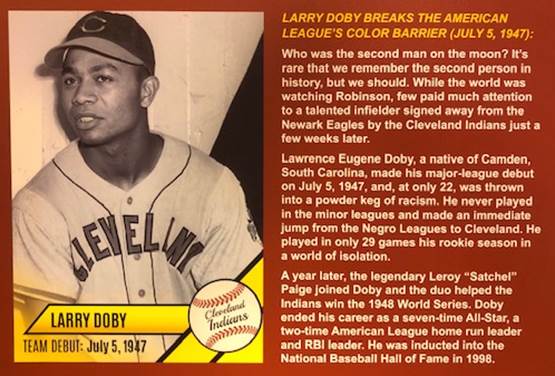

(2) July 5, 1947 – Cleveland Indians (Larry Doby): Doby was a superstar for the Newark Eagles in the Negro Leagues. Bill Veeck owned the Cleveland Indians and had long been a proponent of integration. He signed Larry Doby to be the Barrier Breaker for the Indians. Here is how his story is told in the exhibit at the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum.

President Bob Kendrick of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum likes to say Larry Doby was the second man on the moon. The one whose name we don’t remember because he broke the color line in the American League 81 days after Jackie Robinson did in the National League.

(3) July 17, 1947 – St. Louis Browns (Hank Thompson): The Browns went cross-state and signed two players from the Kansas City Monarchs – Hank Thompson and Willard Brown. Thompson broke the color line on July 17, and Brown would first play on July 19. Neither player finished the season with the Browns, and both returned to the Monarchs. Thompson made a successful return to the Majors in 1949.

Willard Brown was the first Black player to hit a home run in the American League. But he struggled because of the racism endemic in his new surroundings. Also, the hapless Browns were likely not as good as the Monarchs team he had left. Brown never returned to the Majors, but his stellar career in the Negro Leagues put him in the Hall of Fame.

December, 1947: The President’s Committee on Civil Rights issued its report titled “To Secure These Rights,” saying it was past time to secure the rights of all Americans to enjoy full citizenship and equal participation in American life. Recommendations included ending the Supreme Court’s “separate but equal” doctrine and passing laws for equal rights in voting, public accommodations and housing. Below, President Truman receives the report from his committee members.

1948 MLB Season: In 1947, three teams had fielded a total of five Black players. Robinson and Don Bankhead with the Dodgers (Bankhead was the first Black pitcher in MLB). Doby with Cleveland. Thompson and Brown with the St. Louis Browns. Both of the Browns players were gone for 1948, leaving Cleveland and Brooklyn as the only integrated teams. They each added a new Black player, Satchel Paige in Cleveland and Roy Campanella in Brooklyn.

The other teams continued to stand pat. But Harry Truman, in the middle of a re-election campaign, did not.

July 26, 1948 – President Truman Executive Orders: Two historic orders were issued by Truman on July 26, 1948: Executive Order 9980 mandating the elimination of discrimination in the federal workplace, and Executive Order 9981 integrating the armed services. Jim Crow was being chased from the federal government. The orders were issued on “Turnip Day,” which Truman described as an old Missouri farmers’ adage that this is the day to “sow your turnips, wet or dry.” The story behind this was the subject of my MLK message in 2014 (click here).

Truman did what he could by executive order, but Congress and the Supreme Court continued to be major roadblocks.

October 11, 1948 – World Series: The NL pennant winner was the Boston Braves (“Spahn and Sain and pray for rain”). In the AL, it was Cleveland. The Indians took the Series in six games.

Owner Bill Veeck’s mid-season addition of Satchel Paige to the Indians in 1948 had been a big success. Paige went 6-1 with an ERA of 2.48. In three starts by Satchel at Cleveland’s Municipal Stadium, the attendance total was 201,829. Satchel became the first Black pitcher to appear in a World Series.

The Indians top hitter in the Series was Larry Doby who was on his way to a Hall of Fame career. Doby received many accolades, but the temporary euphoria did not speed up baseball integration. The next year, only one new team would add Black players (the Giants). When Larry Doby arrived in Tucson for spring training in 1949, the team hotel was still off-limits to him. When the team left Tucson to complete spring training on the road, this happened…

April 11, 1949 – Texarkana, Texas: The Indians had added a third player from the Negro Leagues – Minnie Minoso joined Doby and Paige on the roster. The three of them made news in Texas. The local stadium would not allow Black players to suit up in the locker room. So the three suited up at the hotel and went out to get a cab to the park. No cabs would take them. They walked to the park in their uniforms – a one-and-a-half-mile trek. Below, a headline and an excerpt from an article reporting on the incident:

“They arrived more than 30 minutes late, but they arrived. Doby was obviously peeved. Paige, an old trouper who lets nothing ruffle him, appeared unmoved. Minoso, carefree in the mold of the average Cuban, laughed about it. The latter was so unperturbed that he slammed out a two-run homer to thrill the taxi drivers who passed him up on their way to see the game.”

Let that sink in. Three future Hall of Famers.

(4) July 8, 1949 – New York Giants (Monte Irvin and Hank Thompson): Hank Thompson had been the Barrier Breaker for the St. Louis Browns in 1947. He returned to the Kansas City Monarchs, but on July 8, 1949, he was again in the Major Leagues, breaking the color line for the New York Giants. Also debuting that day for the Giants was Monte Irvin, a star from the Newark Eagles of the Negro Leagues. Two years later, Irvin and Thompson would start in the outfield in the 1951 World Series with Willie Mays. The three former Negro Leaguers were still with the team when the Giants won the 1954 World Series.

The 1949 Dodgers added Don Newcombe from the Negro Leagues. The early moves to integration by the Dodgers and Giants paid off. From 1947 to 1956, they won eight of the ten NL pennants.

(5) April 18, 1950 – Boston Braves (Sam Jethroe): After the Braves lost the World Series to Cleveland in 1948, owner Lou Perini acknowledged the edge that Larry Doby had given Cleveland. Perini said that when the Braves opened spring training in 1949, he would have a contingent of Black players trying out for the team. After the 1949 season, Perini acquired Sam Jethroe, a former Negro Leagues star who was playing in the minors for the Dodgers. Jethroe not only made the Braves roster in 1950, the 33-year-old was named NL Rookie of the Year.

Perini would soon have his eye on another Negro Leaguer. Hank Aaron signed with the Indianapolis Clowns in late 1951 and quickly learned the indignities of being a Black baseball player. He told this story about a road game in Washington DC:

“I can still envision sitting with the Clowns in a restaurant behind Griffith Stadium and hearing them break the plates in the kitchen after we finished eating. What a horrible sound. Even as a kid [he was 17], the irony of it hit me. Here we were in the capital in the land of freedom and equality, and they had to destroy the plates that had touched the forks that had been in the mouths of Black men. If dogs had eaten off those plates, they’d have washed them.”

The Braves signed Aaron in 1952, and in 1954, after Perini had moved the franchise to Milwaukee, Aaron made his Major League debut. Even though he became one of the best players ever, he could not totally escape racism. After the Braves moved to Atlanta, Aaron broke Babe Ruth’s career home run record in 1974. Although most Atlanta fans cheered for Aaron, the occasion was marred by the hundreds of hate letters he received, many threatening his death.

(6) May 1, 1951 – Chicago White Sox (Minnie Minoso): After three seasons in the Negro Leagues, Minnie Minoso was signed by the Cleveland Indians and played mostly in their minor league system in 1949 and 1950. In 1951, he was traded to the White Sox and became their Barrier Breaker. Despite having better stats, he was runner-up to Yankee Gil McDougald for Rookie of the Year (some say racial bias affected the voting).

In January of last year, Joe Posnanski finished his countdown of the list of the Top-100 players NOT in the Hall of Fame (the “Outsiders”). #1 was Minnie Minoso. #2 was Buck O’Neil. Last month, both were voted in. I’m sure Joe will enjoy updating his list of Outsiders.

1952 – Glacial Pace: Through 1951, only 20 Black players had been added to Major League rosters, and only six teams had integrated. In 1952, no new teams added any Black players. Integration in baseball was proceeding at a glacial pace.

[Kansas City A’s Trivia: One of those 20 was Harry Simpson who made the Cleveland roster in 1951. “Suitcase” Simpson had two stints with the Kansas City A’s in the mid-to-late 1950s.]

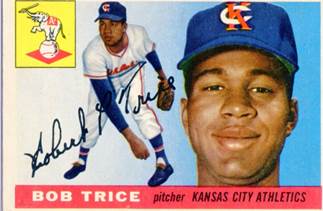

(7) September 13, 1953 – Philadelphia Athletics (Bob Trice): Pitcher Bob Trice played for the Homestead Grays in the Negro Leagues before being signed by the A’s in 1952. His one full season in the Majors was 1954 when he went 7-8. The next season, Trice moved with the team to Kansas City and was “impressive” in spring training wrote Ernie Mehl in the Kansas City Star. But after playing in only four games in KC, Trice went back to the minors and never returned to the Majors.

(8) September 17, 1953 – Chicago Cubs (Ernie Banks): Buck O’Neil had a hard time keeping shortstops while managing the Kansas City Monarchs. Gene Baker was his shortstop in 1949 and 1950 before signing a minor league deal with the Cubs. In 1951, Ernie Banks became Buck’s shortstop, and on September 8, 1953, Ernie also signed with the Cubs. On September 17, Ernie became the Barrier Breaker for the Cubs. Gene Baker was called up from the minors to be Ernie’s roommate. Baker moved to second base, and the two former Monarchs became the double-play combo for the Cubs.

In 1962, the Cubs made Buck O’Neil the first Black coach in the Majors, reuniting him with Ernie Banks (below). Six months later, the Pirates hired the second Black coach in the Majors – Gene Baker.

(9) April 13, 1954 – St. Louis Cardinals (Tom Alston): Jackie Robinson said he was jeered in all cities, but the worst was St. Louis. The Cardinals had no interest in fielding Black players until Anheuser-Busch bought the team in 1953. When Gussie Busch found out there were no Black players, he said, “How can it be the great American game if Blacks can’t play.” He also knew that Budweiser was the top-selling beer among Black customers. Busch quickly went to work, and on opening day in 1954, the Cards had their first Black player, first baseman Tom Alston.

It took a while to trade for and develop Black players, but the reputation for diversity grew and many greats ended up in St. Louis. Lou Brock, Bob Gibson, Curt Flood, Bill White and others were integral to the World Championships that followed.

(10) April 13, 1954 – Pittsburgh Pirates (Curt Roberts): Branch Rickey, the man who signed Jackie Robinson, became the general manager of the Pirates in 1951. The team had not been scouting Black players, and Rickey quickly set up a scouting network. The first Black player to reach the Pirates was Curt Roberts who had played for the Monarchs. Roberts played little for the Pirates, but the Rickey scouting network soon found Roberto Clemente and others. Ricky was replaced in 1956, but his legacy of recruiting Black players was highlighted on September 1, 1971, when the Pirates famously fielded an all-Black and Latino lineup.

(11) April 17, 1954 – Cincinnati Reds (Nino Escalera and Chuck Harmon): Escalera and Harmon broke the color line for the Reds in back-to-back pinch hit appearances.

Two years later, Frank Robinson joined the Reds and was Rookie of the Year. But it would be the 1960s before the Reds spring training camp would be integrated. Below, Reds hitting star Vada Pinson getting a drink at the Red’s camp in Tampa.

May 17, 1954 – Brown v. Board of Education: Although Truman left office in 1953, his Department of Justice had been working in support of cases seeking to end segregation in schools – one of the key goals of his Committee on Civil Rights. When these cases reached the Supreme Court in 1954 under the consolidated title of Brown v. Board, the “separate but equal” doctrine was overturned and schools were ordered to desegregate “with all deliberate speed.”

When Brown v. Board was handed down, there were still five Major League teams maintaining a whites-only policy. Four were in the American League, which was falling behind the National League in talent and excitement. The Yankees were the exception, but they had traditionally had a concentration of the best white players and therefore less need to improve their team. But they may have learned a lesson in 1954. They lost the AL pennant to Cleveland, a team led by AL MVP runner-up Larry Doby. Cleveland then lost the World Series to the New York Giants, a team led by NL MVP Willie Mays. Even Yankee fans appreciated Willie and “The Catch” in the Series.

The difference between the two leagues was notable in the Rookie of the Year awards. The award began in 1947 and only one was initially awarded – it went to Jackie Robinson. The award was split starting in 1949, one for each league. From 1949 to 1959, the NL Rookie of the Year award was won by a Black player eight times. In the American League, zero times. And much the same with MVP. The NL MVP was a Black player nine times in the eleven seasons from 1949 to 1959. In the AL, zero again.

(12) September 6, 1954 – Washington Senators (Carlos Paula): The Barrier Breaker for the Senators was Carlos Paula who played parts of three seasons for the Senators. He was mocked by some of the D.C. press for his accent (Cuban) and baseball intelligence, a precursor to how some of the press treated Latino players like Roberto Clemente (called him Bob and quoted his broken English).

The baseball team was years ahead of the NFL team in the nation’s capital. Owner George Preston Marshall did not want any Blacks to be Redskins (get that?), but he was forced to change. The city had built a new stadium which was on Federal land, and President Kennedy said the Redskins could not use the stadium if the team did not integrate. Reluctantly, Marshall did so in 1962, becoming the last NFL owner to integrate. Eight years after the Senators.

(13) April, 14, 1955 – New York Yankees (Elston Howard): The story of integrating the Yankees is the tale of two Black players on the 1953 roster of its AAA farm team, the Kansas City Blues. The star of the team was first baseman Vic Power who led the league in hitting. This appeared to put him in line to move up to the Yankees in 1954, but Yankee general manager George Weiss said he was waiting for a Black player that met the “high Yankee standards.” Power did not qualify and was traded to Philadelphia where he played the 1954 season, then moving with the A’s to KC for 1955.

Also on that 1953 Blues roster was Elston Howard who had played for the Kansas City Monarchs and was now in the Yankee farm system. Unlike Power, he was not known to date white women, drive a Cadillac or field like a “showboat” nor was he outspoken, a code word for Power not knowing his place. Howard stayed in the minors in 1954 to improve his skills as a catcher and then moved up to be the Barrier Breaker for the Yankees in 1955. He was initially the backup to Yogi Berra and eventually replaced Berra to go on to an excellent career with the Yankees.

Below, Elston Howard with the Monarchs in 1948.

[Kansas City Monarchs Trivia: The Monarchs were by far the primary source of Negro Leaguers to the Majors. Jackie Robinson and Satchel Paige had played for the Monarchs. When Buck O’Neil became the Monarchs manager in 1948, his lineup included five players who were the first or second Black player on a Major League team: Hank Thompson, Willard Brown, Gene Baker, Curt Roberts and Elston Howard. By the time Buck ended his tenure as manager in 1955, several other Monarchs would be playing in the Majors or would soon be there, including Ernie Banks and George Altman.]

December 1, 1955 – Rosa Parks: The civil rights icon was jailed in Montgomery, Alabama, for refusing to give up her seat on a public bus to a white man. In the following 1956 baseball season, the Phillies, Tigers and Red Sox channeled Montgomery and kept their roster bus all-white. Then…drip…drip…drip…over the next three years.

(14) April 22, 1957 – Philadelphia Phillies (John Kennedy): Since the days of Jackie Robinson, Philadelphia (the “City of Brotherly Love”) was known for its racist fans and racial bench jockeying. The Barrier Breaker for the Phillies was John Kennedy who had played in the Negro Leagues for the Birmingham Black Barons and Kansas City Monarchs. Unfortunately, his stay in MLB was only 11 days.

(15) June 6, 1958 – Detroit Tigers (Ozzie Virgil): Ozzie Virgil first played for the Giants who traded him to Detroit where he was the Barrier Breaker for the Tigers.

(16) July 21, 1959 – Boston Red Sox (Pumpsie Green): Boston owner Tom Yawkey was given the opportunity to sign Jackie Robinson and Willie Mays. He passed. It wasn’t personal about the two players. He did not want any Blacks on his team. And the Yawkey family never won a World Series during their 68 years of ownership.

With the other 15 teams integrated, Yawkey bowed to the pressure in 1959, and Elijah “Pumpsie” Green became the Red Sox Barrier Breaker. Green received moral support from Ted Williams who made it a point to warm up with Pumpsie before games. Below, a photo widely circulated in the press showing Ted giving batting tips to Pumpsie. The rest of the roster would not be causing trouble with Ted on board.

Pumpsie played five MLB seasons, but said playing baseball was often overshadowed by the negative daily routines on the road – “Where will you stay, where are you going to eat, what are you going to do, and where are you going to go.”

Post-Pumpsie Green: The integration of the final MLB team did not end discrimination and racism in baseball. I’ll use a couple of Buck O’Neil anecdotes to illustrate.

In 1959, Billy Williams was playing for the Cubs farm team in San Antonio. He grew dissatisfied in mid-season, jumped the team and went home. “I was not accustomed to being treated like an animal away from the baseball diamond. I couldn’t take the bigotry, discrimination and overt racism.” Buck O’Neil was then a scout for the Cubs and was dispatched to urge Williams to return. Who could turn down Buck? Two years later Billy Williams was the NL Rookie of the Year. He is in the Hall of Fame.

In 1964, O’Neil was coaching for the Cubs and heard they were about to trade Lou Brock. Buck had scouted Brock and advised GM John Holland not to make the trade. Buck found himself arguing against an unwritten quota system limiting the number of Black players on one team. The Cubs had five, including stars Ernie Banks and Billie Williams. Holland showed O’Neil complaint letters from season ticket holders, one saying “What are you trying to make the Chicago Cubs into? The Kansas City Monarchs.” Buck lost the argument, and the quota-Cubs traded away a future Hall of Famer to the lucky Cardinals.

The good news was that progress was being made. When baseball expanded in 1961, the new teams were integrated on day-one. There was no need for new Barrier Breakers.

1964-1968 – Harry Truman, Martin Luther King Jr. and Lyndon Johnson: Major League baseball took its time integrating all of its teams, but it was faster than a Congress gridlocked by the filibuster. In 1964, many of the goals of the Truman Committee on Civil Rights had still not been met. That would soon change. The Civil Rights Movement led by Martin Luther King Jr., John Lewis and others was gaining support, including from President Lyndon Johnson. The President applied his negotiating skills to convince Congress to implement key recommendations originally proposed by Truman’s Committee. These efforts led to the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the Fair Housing Act of 1968.

Honoring the Barrier Breakers: Each of the Barrier Breakers played a role in the advancement of civil rights. Martin Luther King Jr. agreed. Don Newcombe, a Dodger teammate of Jackie Robinson and Roy Campanella, attended a meeting with King in 1968. Newcombe said he was honored to hear these words from King: “Don, you’ll never know how easy you and Jackie and Doby and Campy made it for me to do my job by what you did on the baseball field.”

So as you enjoy your Martin Luther King Jr. Day holiday, please raise a toast to the Barrier Breakers. And to President Truman.

Lonnie’s Jukebox – Barrier Breakers Mixed Media Edition

Podcast: Bob Kendrick hosts a podcast series titled Black Diamonds. It is excellent. One of the episodes is on the Barrier Breakers, and Bob’s special guest is Patrick Mahomes whose father, MLB pitcher Pat Mahomes, taught him to respect the Barrier Breakers who paved the way for future generations of Black athletes. Click here (one hour). Below, Patrick in his Monarchs jersey.

Online Program: Last month, the Truman Library hosted an excellent program for the 75th anniversary of Truman’s 1946 order establishing the Committee on Civil Rights (video here; one hour).

Website: My 20 prior annual MLK messages are archived at this link.

Movie Clips: Sidney Poitier died last week at the age of 94. In addition to being a great actor, he was a civil rights activist. Below, with Harry Belafonte at the March on Washington in 1963.

Poitier was also a Barrier Breaker. A month after the March on Washington, the movie Lilies of the Field was released. Poitier starred in the movie and won an Oscar for Best Actor, the first Black actor to do so. Like Jackie Robinson, Poitier felt this was more than a personal accomplishment: “I was happy for me, but I was also happy for the ‘folks.’ We Black people had done it. We were capable. We forget sometimes, having to persevere against unspeakable odds, that we are capable of infinitely more than the culture is yet willing to credit to our account.”

My first memory of Sidney Poitier is from the 1955 movie Blackboard Jungle. He played one of the rebellious students in a racially-mixed high school, but I admit my primary memory of the movie is that it opened and closed with Bill Haley’s “Rock Around the Clock.” Click here for a clip of the opening credits (Poitier, etc.) and the sound of a rock ‘n’ roll anthem.

In 1967, Poitier hit the trifecta, starring in Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, In the Heat of the Night, and To Sir, with Love (click here for clips from the movie and Lulu singing the title song).

RIP Mr. Tibbs.

Jukebox Selection: After its release in 1964, Sam Cooke’s “A Change is Gonna Come” became an anthem for the Civil Rights Movement. I think the lyrics in the refrain can also be applied to the integration of baseball:

“It’s been a long time coming/But I know a change is gonna come, oh yes it will.”

Thanks to the Barrier Breakers, oh yes it did.

Click here to listen to Sam.