This message is a combination of my annual MLK message (since 2002) and the newest Hot Stove post.

The theme for this message started percolating in 2015 when I saw an exhibit at the Kansas City Public Library. The exhibit honored Lucile Bluford as a civil rights activist and for her influential career as a journalist with Kansas City’s premier African American newspaper, the Call. The exhibit chronicled her “separate but equal” litigation with Missouri University when she was denied admission in 1939. Her case and others seeking fairness in education helped lay the foundation for Brown v. Board of Education in 1954.

One of the items in the library exhibit was a 1994 book by Jim Reisler titled Black Writers/Black Baseball: An Anthology of Articles from Black Sportswriters Who Covered the Negro Leagues. I followed up and bought a copy. I got the expected articles on the stars and games, but there were other articles that gave me a deeper appreciation for the civil rights work of these writers. As Lucile Bluford had been an early advocate of education equality, these men were pioneers in the battle to integrate baseball.

This led me to the internet where I found a wealth of material, including a stellar piece by Kansas City-based Negro League historian Larry Lester, titled “Can You Read, Judge Landis?”. Another good source was Chris Lamb’s 2012 book, Conspiracy of Silence.

Civil Rights Milestones: The signing of Jackie Robinson by Branch Rickey is often cited as a major milestone in the history of civil rights. After Jackie took the field for the Dodgers in 1947, other milestones fell into line: President Truman’s integration of the armed forces (1948), the introduction of black rock ‘n’ roll music to white teenagers (when I took notice at age 13, 1954), Rosa Parks on the bus (1955), and (too many to list here) the advances during the Martin Luther King years.

But there are some heroes who stand at the front of this line: a band of black sportswriters. And one Communist. Here’s the story.

Black Newspapers: Black communities in major cities have long been served by weekly newspapers. The first with a full-time sportswriter was the Chicago Defender where Frank Young began his long career in 1907. The early coverage was mostly boxing, football and track, but baseball became more prominent after the Negro National League was founded in 1920 at a meeting at the Paseo YMCA in Kansas City. Frank Young and other black sportswriters were at that meeting and helped write the constitution for the new league.

Some of the papers went beyond support of the Negro Leagues. Long before Branch Rickey heard of Jackie Robinson, black sportswriters were beating the drum for integration of the major leagues. In 1926, Frank Young wrote in the Defender that “the ban against Negro players in the major leagues is a silly one, and one that should be removed.”

By the late 1930’s, their voices became more strident, but they were ignored by the major league owners and their commissioner, Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis. Although denying that a color line existed, the owners continued their “gentlemen’s” agreement to segregate the “national” pastime. The black writers rightfully claimed that sports by their very nature should be based on talent rather than skin color. Prime examples came from boxing and track and field where victories by Jesse Owens and Joe Louis were accepted with wide approval by the white population (sometimes grudgingly). It did not hurt that Owens showed up Hitler at the 1936 Olympics and that Louis won his 1938 rematch against the German Max Schmeling.

Two of the best known among this band of crusading sportswriters were Wendell Smith and Sam Lacy.

Wendell Smith: Smith is generally considered the dean of black sportswriters. He grew up in Detroit where he pitched American Legion ball. After winning a pitchers’ duel 1-0, a scout for the Tigers signed the losing (white) pitcher and told Smith he would also like to sign him, but could not. Smith has said this was his inspiration to become a sportswriter and work for baseball integration.

Wendell Smith and Jackie Robinson

Smith joined the prestigious Pittsburgh Courier in 1937 and covered the two premier black teams based in the area: the Homestead Grays and the Pittsburg Crawfords. Over the next ten years at the Courier, he was a prominent voice in the cause to integrate baseball. It helped that the Courier was a widely circulated and respected newspaper far beyond its Pittsburgh roots.

In 1939, Smith wrote a series of articles that ultimately proved instrumental in breaking the color line. To counter the argument that current major leaguers opposed integration, Smith interviewed forty players and all eight National League managers. This was not always easy because Smith, usually denied a press pass because of his race, did not have access to locker rooms or press boxes. Almost every person he interviewed thought integration was fine and that there were black players who belonged in the major leagues.

Sam Lacy: Lacy was an African American/Native American sportswriter who grew up in Washington D.C. His father was a big Senators fan who often took his son to games at Griffith Stadium where they sat in the Jim Crow section. The Senators had an annual parade for opening day, and Lacy’s father often attended. At age 79, his father was at the parade and cheering the team. A player walking by spit on his father. His father never went to another game. As a teenager, Lacy sold peanuts and popcorn in the black section at the stadium and saw both black and white teams. So he knew first hand that there were black players who should be in the major leagues.

Lacy joined the staff at the Washington Courier in 1934. In 1937, he met with Washington Senators owner Clark Griffith to discuss integration. His pitch was that great black ballplayers like Josh Gibson, Buck Leonard and Cool Papa Bell were coming into Griffith Stadium when the Senators were out of town. Anyone could see that such players could help the lowly Senators. Griffith told Lacy to forget it. The “climate” was not right. In 1940, Lacy moved on to Chicago for three years at the Defender, and then returned to the D.C. area to write for the Baltimore Afro-American.

The Communist: He was a sportswriter who loved baseball. He was also a Communist whose cause was social justice. Lester Rodney, white and Jewish, grew up in New York City. In 1936 he joined the staff of the Daily Worker and Sunday Worker, newspapers for the Communist Party USA. Over the next ten years, he and others at the paper wrote hundreds of articles in a major campaign to end baseball apartheid. The campaign was consistent with the paper’s general support for workers and unions – Rodney noted that even white players did not receive a fair share of the fruits of their labor (an early signal of the future players’ union).

The Daily Worker had a special attribute not enjoyed by the black newspapers. It had white readers, some of whom were social activists, politicians and union members who could be helpful to the cause. He was also able to join the Baseball Writers Association, which gave him access to press boxes and locker rooms.

To give a flavor of the paper’s tone, here is an announcement published on August 13, 1936:

The Crime of the Big Leagues!

The newspapers have carefully hushed it up!

One of the most sordid stories in American sports!

Though they win laurels for America in the Olympics – though they have proven themselves outstanding baseball stars – Negroes have been placed beyond the pale of the American and National Leagues.

Read the truth about this carefully laid conspiracy.

Beginning next Sunday, the Sunday Worker will rip the veil from the “Crime of the Big Leagues” – mentioning names, giving facts, sparing none of the most sacred figures in baseball officialdom.

Mainstream (white) newspapers indeed hushed up the color line arguments. There were a few white sportswriters who wrote in support of integration, but most ignored the issue, preferring to enjoy their symbiotic relationship with the teams. The writers got good copy to increase newspaper sales, and the teams got what amounted to free advertising. Why rock the boat?

Expanding on his Olympics comment, Rodney wrote “There is not much difference between the Hitler who, like the coward he is, runs away before he will shake Jesse Owens’ hand, and the American coward who won’t give the same Negro equal rights, equal pay and equal opportunities.”

Another point often made by Rodney was that it was not just the black players who were being cheated. White major league fans were being denied their right to see some of the best players in baseball.

World War II – “Double V”: It is sad to say that it was necessary, but the war was a big boost to the cause of integration. Less than two months after Pearl Harbor, the Pittsburgh Courier published a letter written by 26-year-old cafeteria worker James G. Thompson. He proposed that the dedication to victory abroad be paired with a fight for victory against similar forces at home. The first V would be victory over the enemies without, the second V for a victory over the enemies within. Hitler was hardly the sole purveyor of racism.

The letter prompted the Courier to start the “Double Victory” campaign, a/k/a the “Double V” campaign. The campaign became a nationwide effort with many other black newspapers joining in. There was a steady stream of articles and editorials through the rest of 1942, and photos, posters and drawings of variations of the Double V were widely distributed. Double V events were held, including Double V days at the ballparks.

The Double V campaign complemented the ongoing work of the Courier’s baseball writer Wendell Smith. It also blended in perfectly with a campaign being launched by Lester Rodney.

Can You Read, Judge Landis?: On May 6, 1942, the Daily Worker published an open letter from Lester Rodney to Commissioner Landis. The letter began with the news that the first casualty lists from the war were in and included both black and white soldiers who were dying for the preservation of the country and all it stood for – “yes, including the great game of baseball.” He said that Landis and the owners now had a much greater responsibility to set an example of democracy to help unify the country in “the grim fight against the biggest Jim Crower of all – Hitler.”

Rodney’s letter reminded Landis that many major league managers and players had voiced their support for integration. The plea to Landis at the end of the letter, “The American people are waiting for you. You’re holding up the works.”

The letter was reprinted in many black newspapers. The Daily Worker kept up the pressure with articles and headlines that advanced the theme: “Can You Read, Judge Landis?”; “Can You Hear, Judge Landis?”; “Can You Talk, Judge Landis?”. After the Kansas City Monarchs played a white team of former all-stars at Wrigley, Rodney checked the attendance for a White Sox/Tigers double-header played that same day in the same city. The Monarchs, with Satchel Paige pitching, outdrew the other game by more than ten thousand fans, prompting this Daily Worker headline: “Can You Count, Judge Landis?”

Landis Can Read: The barrage of articles from the black sportswriters and Lester Rodney were the likely reason Commissioner Landis felt the need to issue a formal statement. On July 17, 1942, he did so, saying that there was no rule in organized baseball prohibiting black participation “to my knowledge”. “That is the business of the manager and the club owners. The business of the Commissioner is to interpret the rules and enforce them.”

Although there was plenty of skepticism about the statement, it was treated as a new opening to apply pressure on the owners. Wendell Smith: “Now ‘The Great White Father’ of Baseball has finally spoken. The work of these veteran writers has not been in vain. Landis has left the issue to the owners and fans. The end is in sight.” Not quite, but it was a start.

Little help came from the white press. J. G. Tyler Spink responded to the Landis statement with an editorial in his Sporting News (the so-called “Bible of Baseball”). He defended segregation and supported the tired arguments of the owners. Spink warned of race riots at games and said there were no blacks good enough to play in the major leagues. He denigrated the black and Communist sportswriters as “agitators.”

The push from sportswriters then moved to demanding that owners give tryouts to black players. As an interesting piece of baseball trivia, one of the first tryouts of black players had already occurred in March of 1942. Herman Hill, a West Coast correspondent for the Pittsburgh Courier, made an unannounced visit to the White Sox training camp in Pasadena. He brought with him two black college players, Jackie Robinson and Nate Moreland. Manager Jimmie Dykes agreed to take a look and was impressed with Robinson. Dykes mentioned the “unwritten law” on segregation and nothing came of the tryout. In any event, the draft soon took Robinson to the army.

More Delays Plus J. Edgar Hoover: The campaigns by the black newspapers for equal rights, including the Double V program, drew the attention of several federal agencies. The claim was that such demands to address racism during the war were unpatriotic and undermined the morale of the country. The FBI was building lengthy files on the black newspapers, and J. Edgar Hoover called for them to be charged with sedition. Roosevelt’s Attorney General Francis Biddle rebuffed bringing any indictments, but the message was delivered and much of the rhetoric was tempered until the war was over.

Lester Rodney was also being monitored by the FBI. He was considered a double security threat: a civil rights activist and a Communist. Hoover wrote in his book that Rodney’s “On the Scoreboard” columns were “slanted to promote the [Communist] party views” and amounted to “propaganda.”

The intimidation from the agencies and the general fatigue of war slowed the momentum for baseball integration. And the owners and Judge Landis remained agile at finding ways to evade and delay. There was one exception: The Brooklyn Dodgers. But that was a secret that even Hoover had not uncovered.

Branch Rickey: After several years as a successful general manager for the Cardinals, Branch Rickey moved to the Dodgers in September of 1942. He became a part owner and the GM. In early 1943, Rickey met with the board of directors and got permission to explore finding the right kind of player to break the color line. This began a process that Rickey kept under the radar as he laid plans for someday integrating baseball. Two events after the 1944 season advanced the process:

On November 25, 1944, Commissioner Landis died. The owners needed a new leader.

On November 28, 1944, Jackie Robinson ended his military service. The next summer, he was on the field with the Kansas City Monarchs.

The New Commissioner: In April of 1945, the owners named Happy Chandler to succeed Landis. Chandler was a U.S. Senator from Kentucky and left that post in November to assume his new position as commissioner. If the owners thought hiring a politician from a segregated state would keep integration away, they were going to be disappointed. Soon after Chandler’s appointment was announced, Wendell Smith and his fellow reporter Rick Roberts from the Pittsburgh Courier met with Chandler to see where he stood on integration. They were not disappointed. Chandler told them “If a black boy can make it in Okinawa and go to Guadalcanal, he can make it in baseball.”

Spring Training – 1945: The People’s Voice, based in Harlem, was a militant black newspaper published in the 1940’s by controversial Congressman Adam Clayton Powell. The paper’s sports editor was Joe Bostic, and he became another voice in the fight for baseball integration. In April of 1945, he showed up unannounced at the Dodgers spring training camp with two Negro League players (not stars) and demanded a tryout. Branch Rickey was not amused at the tactic – he had his own (still secret) agenda for integration. Nevertheless, he consented to the tryout, and the black press treated that as a big success. Wendell Smith wrote that it was a great step forward and praised Rickey for his courage.

In Boston, city councilman Isadore Muchnick was pushing the Red Sox and Braves to grant tryouts. The Red Sox agreed, and Muchnick asked Wendell Smith to find the players. Smith chose Jackie Robinson, Sam Jethroe and Marvin Williams, all established Negro Leaguers and thus a better test than Bostic had arranged with Brooklyn. The tryout was granted, but only because of the political pressure. The Red Sox had no true interest. Owner Tom Yawkey would later turn down a chance to sign Willie Mays and continued to keep his Red Sox segregated until 1959. He was the last holdout in what Lester Rodney had labeled in 1936 as “The Crime of the Big Leagues!“.

Jackie Robinson/Wendell Smith/Branch Rickey: The Boston tryout had a silver lining. Branch Rickey asked Wendell Smith to come straight to Brooklyn and report on the tryout. Smith used this occasion to recommend that Rickey sign Robinson. Rickey had heard about Robinson’s football stardom at UCLA, but was unaware of his superior baseball talent. The case for Robinson was also made by Sam Lacy in a preseason article in Negro Baseball, saying that Jackie was “the ideal man” to break the color line because he had played with and against whites. Lacy also met with Rickey and thought he was sincere about integration.

Rickey moved quietly during the 1945 season, and he even set up a smoke screen by saying he was looking to establish a Brooklyn black team in a new Negro League to be formed. This gave him cover as he scouted black players and set up the signing of Robinson. Wendell Smith stayed in touch with Rickey and helped orchestrate the process. Rickey also had an economic incentive in the secrecy. He wanted to line up other Negro Leaguers because he knew that once he made his first signing other teams would begin to sign black players.

The stars finally aligned. Rickey had the right player. He assumed that incoming Commissioner Chandler would not intervene. New York politicos were saying the right things and a new state law banned discrimination in hiring. The unions and black newspapers were pushing hard. But maybe most of all, Rickey knew it was time to do the right thing (and get that jump on the other teams for talent). So Jackie Robinson was signed in the fall of 1945 and assigned to the Dodgers’ Montreal farm team for the 1946 season.

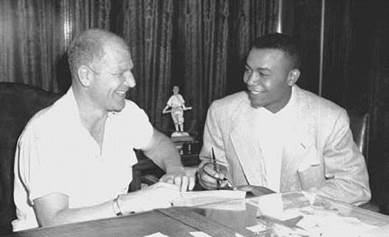

Rickey Signs Robinson

Rickey quickly signed two other future Hall of Famers out of the Negro Leagues – Roy Campanella and Don Newcombe who were assigned to the Dodgers’ farm team in Nashua, NH. Jackie moved up to the Dodgers in 1947, followed by Campy and Newcombe in 1948.

After The Signing: The immediate response from a portion of the white press and players from the South was negative and often harsh. J. G. Taylor Spink’s Sporting News described Robinson as “definitely dark…the hue of ebony.” The paper said if Robinson were white and six years younger, he might make Brooklyn’s AA team in Newport News. It should be noted that Spink, Landis and the owners were not outliers on segregation. Jim Crow, prejudice and racism reached into many parts of the country, not just the South.

But Branch Rickey was prepared. He had been working on this for almost three years. To assure that Jackie had support, Rickey hired Wendell Smith to travel and room with Jackie, both when he played for Montreal and then his first year in Brooklyn. Sam Lacy also often took on this role. Smith and Lacy knew the Jim Crow issues that black players had in the Negro Leagues and so were familiar with arranging housing and meals in cities where Jackie could not be with his teammates.

Smith and Lacy were also often barred from press boxes, but they got the enjoyment of filing stories about Jackie. Those columns sold a lot of papers. Smith also ghost wrote a regular newspaper column for Jackie and did the same for Jackie’s first autobiography. He called himself Jackie’s Boswell.

It was not easy for Jackie, especially his first year in the majors. But eventually the players and owners got back to mostly baseball. The Sporting News was still not a fan of integration, but they could not deny Jackie’s talent – they named him Rookie of the Year. Rickey’s plan to get a jump on the other clubs also worked out well. Robinson, Campanella and Newcombe were a core part of the team that that became immortalized as the “Boys of Summer.” The Dodgers won six pennants from 1947 to 1956 and won the 1955 World Series.

The American League: Wendell Smith was also in the middle of integration in the American League. Cleveland owner Bill Veeck, already known as a maverick, wanted to break the color line in the AL. Veeck said that the strongest influence on his decision to select Larry Doby came from Wendell Smith. Veeck: “I had known Wendell since ’42. So Wendell and Abe [Saperstein] and I met a couple of times and we arrived at Larry Doby as the best young player in the [Negro] league.” Rickey was also considering Doby, but backed off after Smith told him that Veeck was seeking Doby – Rickey was glad to hear that he would have support from a team in the other league.

Veeck Signs Doby

Doby took the field for the Indians in 1947, just weeks after Jackie did for Brooklyn. When Veeck added Satchel Paige in 1948, J. G. Taylor Spink blistered Veeck in the Sporting News, saying it was demeaning to baseball and a publicity stunt to bring in the “old man.” Paige drew some of the biggest crowds in the history of baseball, and his pitching helped the Indians win the pennant. To top it off, the Tribe won the 1948 World Series.

Spring Training – 1946 to 1964: Spring training presented a special challenge. Most of the teams trained in Florida which was heavily steeped with Jim Crow restrictions. Again, black sportswriters were in the forefront. They were often instrumental in persuading teams to fight for their players in Jim Crow situations. This was a very slow process. A good (bad?) example was recounted in a 1949 column by Sam Lacy titled “Indians Tan Trio Compelled to Walk to Ballpark by Bigoted Texas Taxis.” The Indians were playing an exhibition game in Texas, and cab drivers refused to take Larry Doby, Satchel Paige and Minnie Minoso to the ballpark. So the three walked to the park in their uniforms (blacks could not dress in the locker room at the park).

The Dodgers sidestepped the issue by moving their spring training camp to Havana in 1947 and Santo Domingo in the Dominican Republic for 1948. They then opened Dodgertown in Vero Beach in 1949, providing housing and meals within the camp for all players. Below, on their way to spring training in Santo Domingo in 1948: Sam Lacy, Dodger player Dan Bankhead and Wendell Smith.

In 1948, Wendell Smith moved to the Chicago American to become the first black sportswriter for a major daily. In 1961, he spearheaded a series of articles attacking the continued segregation at spring training. Even though all teams now had black players, only the Dodgers offered fully integrated Florida spring training. One of the articles included a touching photo of Vada Pinson of Cincinnati getting a drink in Tampa at the Reds’ camp. The players association endorsed the Chicago American campaign and, despite objections from some Florida towns, all clubs soon took action to fully integrate spring training.

The Negro Leagues: Although a natural result of integration was the bittersweet demise of the Negro Leagues, the sportswriters did not abandon the stars from the past. They pushed for the admission of Negro Leaguers to the Hall of Fame. The HOF agreed to the idea, and Sam Lacy and Wendell Smith were on the original 10-man selection committee. The first inductee was Satchel Paige in 1971. After the Paige selection was announced, the Hall of Fame said that Negro Leaguers would be honored in a separate (but equal?) wing rather than the revered plaque room. There was a big public outcry. The Satchel Paige response: “I was just as good as the white boys. I ain’t going in the back door of the Hall of Fame.” The HOF quickly reversed itself, and Satchel joined Babe Ruth and the other greats in the plaque room.

Hall of Fame – Baseball Writers: In 1948, the color line of the Baseball Writers Association of America was removed, and Sam Lacy and Wendell Smith were allowed to join. The BBWAA is the group empowered to elect players to the Hall of Fame. They also have their own wing at the Hall of Fame honoring the annual winners of the J. G. Taylor Spink Award [Yes, named after the man who thought baseball integration would end in race riots and ridiculed the signing of Jackie Robinson and Satchel Paige.] The award is given in recognition of meritorious contributions by a baseball journalist. Wendell Smith was the first black to win the award, in 1993, and Sam Lacy won in 1997. The one-time Communist Lester Rodney will hopefully join them some day.

I have a poignant image that sticks in my mind on Wendell Smith. Often barred from the press box in the early days, he sat in the stands with the fans, his typewriter on his lap to prepare his next column. Smith left the Courier in 1947 and moved on to Chicago for newspaper and TV work. In October of 1972, Jackie Robinson died at age 53. Smith was too ill to attend the funeral, but wrote Jackie’s obituary from his hospital bed. Smith died a month after Jackie at the age of 58.

After the color line was broken, Sam Lacy continued to push for equal rights, including equal pay for athletes of color and to end segregation when teams were on road trips. “I pointed out to Chub Feeney that he had guys like Willie Mays and Monte Irvin and Hank Thompson holed up in some little hotel while the rest of the players…were staying at the famous Palace. Chub looked at me and said, ‘Sam, you’re right.’ He got on the phone to [Giants owner] Horace Stoneham, and that was the end of that.” Lacy stayed with the Baltimore Afro-American for over 60 years, writing his last column from his hospital bed a few days before he died in 2003 at age 99.

Lester Rodney left the Daily Worker and Communism in 1958. The FBI continued to monitor him, eventually building a 437-page file. Nothing came of it. He moved to California to work in advertising and then became, remarkably, the religion editor at a Long Beach newspaper. In his 80’s, he was a ranked senior tennis player. He died in 2009 at age 98. There is a superb 11-minute video on him here.

Bizarre Trivia: Happy Chandler became known as the “players’ commissioner” for his role in baseball integration and the establishment of a players’ pension fund. So naturally the owners did not renew his contract in 1951. They instead offered the job to J. Edgar Hoover. Hoover turned it down, leaving him available to soon start building his 16,659-page file on Martin Luther King. Spurned by Hoover, the owners chose National League President Ford Frick. The names of both Hoover and Frick had been floated in 1945 when Chandler was selected.

Martin Luther King Jr. Day: As this holiday is celebrated next Monday, there will be deserved accolades for Martin Luther King and other civil rights luminaries like Branch Rickey and Jackie Robinson. But I hope you will join me in toasting Wendell Smith, Sam Lacy, Lester Rodney and the other writers who labored for years on a unique cause that helped ignite the Civil Rights Movement.

Lonnie’s Jukebox: I don’t have a music selection from the era covered by this post. But one of my favorite songs will work fine.

In 1964, Sam Cooke wrote a song inspired by his being turned away from a whites-only motel. He and some of his band members were jailed after they strongly objected and refused to leave. Soon after that, Sam wrote “A Change is Gonna Come” which became an anthem for the Civil Rights Movement.

The refrain nicely captures the life work of Wendell Smith, Sam Lacy and Lester Rodney. “It’s been a long, a long time coming / But I know a change gonna come, oh yes it will.” And, oh yes it did.